Daily Life In The Ottoman Empire (8 page)

Read Daily Life In The Ottoman Empire Online

Authors: Mehrdad Kia

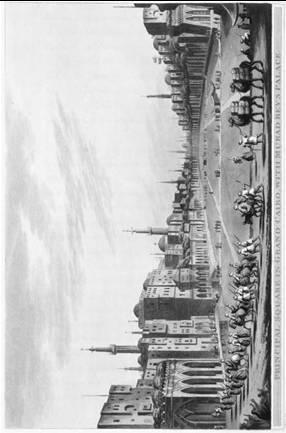

Principal square in Grand Cairo,

with Murad Bey’s Palace, Egypt, c. 1801. A column of soldiers crossing a large

square surrounded by buildings with domes and minarets. Other people are in the

square in the distance. From

Views in Egypt, Palestine, and Other Parts of

the Ottoman Empire.

Thomas Milton (London, 1801–1804).

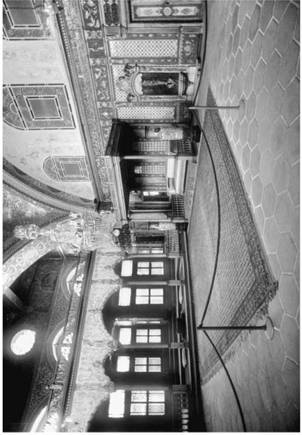

PALACE

As their territory expanded, new urban centers were added

to the emerging empire, allowing Ottoman sultans to build palaces, mosques,

bazaars,

bedestans

(covered markets for the sale of valuable goods),

schools, bathhouses,

hans

(inns), and fountains. Only after the conquest

of Constantinople in May 1453 did the Ottoman sultan Mehmed II, known as the

Conqueror (

Fatih)

, introduce the idea of a permanent residence for the

sultan. The construction of Istanbul’s world-renowned Topkapi (Canon Gate)

Palace, built on “Seraglio Point between the Golden Horn and the Sea of

Marmara,” began in 1465 and ended 13 years later in 1478. Built on a hill

looking down at the Bosphorus, the location of the new palace offered both

defensibility and stunning views. A high wall with several towers and seven

gates surrounded the palace. At the height of Ottoman power, the palace housed

4,000 residents.

The palace was a complex of many buildings centered on four

main squares or sections: “an area for service and safety also known as the

Birun, or outer section”; an “administrative center where the Imperial Council

met”; an “area used for education, known as Enderun, or inner section”; and “a

private living area, dominated by the Harem or women’s section.” Three

monumental gates marked the passages of the palace. These began with the first

or Imperial Gate (Bab-i Hümayun); followed by the second or Middle Gate, known

also as the Gate of Salutation (Bab-üs Selam); and finally the third gate,

known as the Gate of Felicity (Bab-üs Saadet).

The first palace courtyard was the largest of the four, and

functioned as an outer park that contained fountains and buildings such as the

imperial mint. At the end of this courtyard, all those riding a horse had to

dismount and enter the second court, or the Divan Square, through the Gate of

Salutation, or the Middle Gate. With exception of the highest officials of the

state and foreign ambassadors and dignitaries, no one could enter the second

courtyard, which housed a hospital, a bakery, army quarters, stables, the

imperial council, and the kitchens. This courtyard served principally as the

site where the sultan held audience. At the end of this courtyard stood the

Gate of Felicity, which served as the entrance to the third courtyard, also

known as the inner court, or the

enderun.

It was in front of this gate

that the sultan sat on his throne during the main religious festivals and his

accession, while his ministers and court dignitaries paid him homage, standing

in front of their royal master. It was also here that, before every campaign,

the sultan handed the banner of the prophet Muhammad to the grand vizier before

he departed for a military campaign.

Beyond the Gate of Felicity lay the inner court and the

residential apartments of the palace. No one could enter this court without

special permission from the sultan. In this inner section of the palace, the

sultan spent his days outside the royal harem surrounded by a lush garden and

the privy chamber (

has oda)

, which contained the royal treasury and the

sacred relics of the prophet Muhammad, including a cloak, two swords, a bow,

one tooth, a hair from his beard, his battle sabers, a letter, and other

relics.

The audience chamber, or chamber of petitions (

arz odasi

),

was located a short distance behind the Gate of Felicity in the center of the

third courtyard. The chamber served as an inner audience hall where the

government ministers and court dignitaries presented their reports after they

had kissed the hem of the sultan’s sleeve. The mosque of the eunuchs and the

apartments of the palace pages, the young boys who attended to the sultan’s

everyday needs, were also located here. Another “important building found in

the third courtyard was the Palace School,” where Ottoman princes and the

promising boys of the child levy (

devşirme)

“studied law,

linguistics, religion, music, art, and fighting.” From its inception in the 15th

century, the palace school prepared numerous state dignitaries who played a

prominent role in Ottoman society. Only in the second half of the 19th century

did the ruling elite cease using the palace school. The fourth and the last

courtyard included the royal harem, which comprised nearly four hundred rooms

and served as the residence for the mother, the wives, and children of the

sultan and their servants and attendants.

In 1856, a new palace called Dolmabahçe replaced Topkapi as

the principal residence of the sultan and his harem. Dolmabahçe “embraced a

European architectural style” and “was designed with two stories and three

sections, with the basement and attic serving as service floors.” The “three

sections of the palace were the official part . . ., the ceremonial hall . . .,

and the residential area (HAREM).” The “official section was used for affairs

of state and formal receptions,” while the second section “was used for formal

ceremonies.” The harem or the “private residential area of the palace” occupied

“the largest area of the palace” and included “the sultan’s personal rooms: a

study, a relaxing room, a bedroom, and a reception room.” The mother of the

sultan also had her own rooms “for receiving, relaxing, and sleeping.” Each of “the

princes, princesses, and wives of the sultan (

kadinefendiler)

also had

his or her own three-or-four room apartments in the palace, living separately

with their own servants.”

In 1880, the Ottoman sultan Abdülhamid II moved the royal

residence to the Yildiz (Star) Palace, where an Italian architect Riamondo

D’Aronco was commissioned to build new additions to the old palace complex. The

new structures, built of white marble, were European in style and contained the

sultan’s residence, a theater and opera house, an imperial carpentry workshop,

an imperial porcelain factory to meet the demands of upper-class Ottomans for

European-style ceramics, and numerous governmental offices for state officials

who served their royal master. The only section of the Yildiz Palace accessible

to foreign visitors was the

selamlik,

or the large square reception

hall, where the sultan received foreign ambassadors. In the royal harem, which

was hidden within a lush and richly wooded park and was known for its rare

marbles and superb Italian furniture, Abdülhamid II received his wives and

children. At times he spent the evening there with a favorite wife and children

and played piano for them. Within the park, there also lay an artificial lake,

on which the sultan and his intimates cruised in a small but elegant boat.

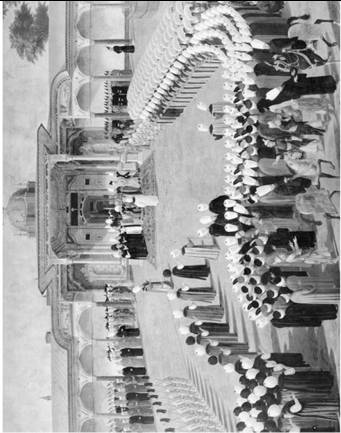

Reception at the court of Sultan

Selim III at the Topkapi Palace, Istanbul. Anonymous, 18th century.

HAREM

In Europe, the “oriental harem” conjured up images of

exotic orgies and violent assassinations, in which a turban-clad monarch acted

as a bloodthirsty tyrant, forced by his “oriental” instincts to murder his real

and imagined enemies while sleeping with as many concubines as he fancied every

night. According to this wild and romantic image, the sultan’s power over all

his subjects was unfettered and his control over the women of the harem

unlimited. Thus, in the European imagination, the harem not only symbolized

free sex but also a masculine despotism that allowed men, especially the

sultan, to imprison and use women as sexual slaves. The meaning of women’s

lives was defined by their relationship to the male master they served. They

dedicated their entire lives to fulfilling the fancies of a tyrant who viewed

them as his chattel.

In this imaginary world, constructed by numerous European

stories, travelogues, poems, and paintings, Muslim men appeared as tyrannical

despots in public and sexual despots in private. In sharp contrast, Muslim

women appeared as helpless slaves without any power or rights, who were

subjected to the whimsical tyranny of men. Not surprisingly, therefore, the

Europeans who travelled to the Ottoman domain were shocked when they realized

how different the reality was. First, they quickly recognized that the notion

of each Muslim man being married to four wives and enjoying a private harem of

his own was absurd and laughable. If Islam allowed Muslim men to marry four

wives, it did not follow that the majority of the male population in the

Ottoman Empire practiced polygamy. As late as 1830s, the number of men in Cairo

who had more than one wife did not exceed five percent of the male population

in the city. By 1926, when the newly established Turkish Republic abolished

polygamy, the practice had already ceased to exist.

Far from being devoted to wild sexual orgies, the Ottoman

palace was the center of power and served as the residence of the sultan. As

already mentioned, the palace comprised two principal sections, the

enderun,

or the inner section, and the

birun,

or the outer section. The two

sections were built around several large courtyards, which were joined by the

Gate of Felicity, where the sultan sat on his throne, received his guests, and

attended ceremonies. The harem was the residence of the sultan, his women, and

family. A palace in its own right, the harem consisted of several hundred

apartments and included baths, kitchens, and even a hospital.

Three separate but interconnected sections formed the

harem. The first section housed the eunuchs, while the second section belonged

exclusively to the women of the palace. The third and final section was the

personal residence of the sultan. The apartments of the imperial harem were

reserved for the female members of the royal family, such as the sultan’s

mother (

valide sultan)

, his wives, and his concubines. Many concubines

in the royal harem came from the Caucasus. The “sultans were partial to the

fair, doe-eyed beauties” from Georgia, Abkhazia, and Circassia. There were also

Christian slave girls and female prisoners of war who were sent as gifts to the

sultan by his governors. These girls underwent a long process of schooling and

training, which prepared them for a new life in the imperial palace. The most

powerful woman of the harem was the mother of the sultan, who lived in her own

apartment surrounded by servants and attendants. Her apartment included a

reception hall, a bedroom, a prayer room, a resting room, a bathroom, and a

bath. It was second in size only to the apartment of the sultan.