Damn His Blood (44 page)

Authors: Peter Moore

There is also a great deal of evidence to support what he said. At the assize witnesses testified that Clewes had been at Pershore Fair on 25 June 1806 and that he had ordered marl to be brought up to the barn. James Taylor’s connection with the murders was backed up by John Rowe’s two statements (one to Pyndar in 1808 and the other to Smith in 1830) and by the surgeon Pierpoint, who was convinced Heming’s injuries had been caused by a blood stick. In addition, Henry Halbert could have testified that Heming returned to Church Farm on Midsummer night, and Mary Chance could have confirmed that he had fled through the meadows towards Trench Wood and Netherwood early on 25 June. By March 1830 both Halbert and Chance were dead. Had they lived, more of Clewes’ story may have been confirmed.

Less obvious but equally persuasive are the little details – derided as ‘artful’ by Banks. Clewes recalled the precise spot in the barn where each of the men had stood as the blow was struck. He remembered how the dogs and rats had scratched holes in the wall where the grave was dug, and he asserted that Banks gave him the money in two parcels. None of these splashes of colour were vital to his narrative, but he provided them nonetheless, as if they were seared in his memory. If Clewes’ statement was a complete invention, then it would have concealed as many details as possible, knowing one slip would expose him. As it was, Clewes had the confidence to litter his testimony with vivid asides and even snippets of dialogue. The Captain’s demand is also darkly familiar: ‘Damn your body. Don’t you never split!’ It’s a vicious curse, strikingly reminiscent of the language Evans is known to have used elsewhere throughout the summer.

And the roles Clewes allots to the farmers seem to tally with what we know about their characters. Taylor plays the incorrigible villain, Banks the Captain’s able deputy, John Barnett the aloof financier, and Heming the slinking rogue. Meanwhile, the Captain remains the dominant personality throughout, his actions fully in line with his military background and instincts. He bullies Clewes into meeting them at the barn, orders Heming about, bides his time and plots his trap. This version of events is more plausible than the alternative scenario: that Clewes killed Heming alone. The improvisation and resolution that would have been required to remove Heming in the wake of his return to Oddingley on Midsummer night was most likely to have come from Captain Evans. It was a dangerous and fluid situation, one that must have reminded the Captain of the fraught campaigns of his military days.

Here there is no real reason to doubt Clewes’ statement. Heming’s ambush was devised on 25 June, a plot which emerged as the hours passed. Indeed, at seven in the morning, when Banks was dispatched to Netherwood, it seems that the Captain had little idea of what to do with Heming. The decision to have him killed must have come at some point during the day. It was a nimble and ruthless move. Heming had a brittle character: if he could be persuaded to kill a man, it seems likely that he could also be convinced to confess. In such a desperate situation it was logical for the Captain to turn to James Taylor, a man with such a foul reputation he was considered ‘the biggest rogue in the county’. And once Evans had brought Taylor into the scheme, he would only have to ensure that Clewes was not kept informed. If Clewes had foreknowledge of the plan to kill Heming he might refuse them entry to his barn or warn the fugitive and allow him to escape. Time was crucially important. The job had to be done – and concealed – that night.

Thereafter, Heming’s murder bears the marks of an intellect far closer to that of the Captain than Clewes. The blood stick was a suitable murder weapon because it was silent. A shotgun or pistol would have roused all Netherwood and caused the same problems that Heming had faced the day before. Its second quality was that it allowed for a clean execution. Several forceful blows would shatter Heming’s skull in an instant, but no blood would be spilled on the floor or splashed against the bricks. There would be no telltale signs. ‘There was no blood, not a spot on the floor,’ Clewes said in his confession – a slight detail but one that rang true.

Heming was attacked seconds after they entered the barn. Once again the scene fits together. The barn door creaks as it swings open. Heming flinches beneath the straw as he hears the boots of four men softly enter from the fold-yard. Who are they? Could it be Evans, who has promised to come with his money? Or might it be Clewes or one of his servants? Why are there

four

people? There is a pause. Heming can see the dull glow of a lantern through the straw. A second later, through the thick summer air, comes the sound of the Captain’s voice. Heming answers timorously. He puts his hands down to push himself up towards the light. There is the gentle tread of feet, the smooth rustle of wood against fabric, the smell of burning oil, and then there is only darkness.

Clewes did not have an opportunity to intervene, and once Heming was dead, he was hopelessly implicated. Just as the Captain had hired someone to remove Parker, he had subsequently engaged Taylor to dispose of Heming. This is a pattern: a delegation of tasks or a gift for putting others in harm’s way before himself, demonstrated once again perhaps by the fact that the murder took place at Netherwood and not Church Farm. Once the body was buried, Clewes would have been ill advised to have dug it up and carted it about the parish. And how could he have explained the presence of a corpse in his barn if it was found?

As for George Banks’ attacks, all presented eloquently and persuasively, several of them can be unpicked. His main argument, that Taylor was an elderly man physically incapable of murder, contradicted what he described elsewhere. Banks asserted that Taylor could not possibly have killed Heming as he was travelling at the time of the two murders. ‘I shall show you that on the day the Rev. Mr Parker was shot, in the morning of that day he [Taylor] went to Cotheridge about 11 miles from Droitwich, and thence on to the Hyde Farm near Bromyard in Herefordshire, a distance of about 23 miles from Droitwich, to attend to some cows of a Mr Gardiner’s, which were ill of the black water.’

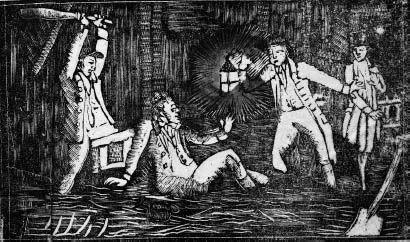

A popular reconstruction of Richard Heming’s murder that shows his lantern jaw and high forehead. It also gives us our only glimpse of Captain Evans

These claims served only to undermine his argument. If the farrier could complete 40-mile round trips in less than two days, stopping to drive fleams into the arteries of diseased cows, then murdering Heming wouldn’t have been difficult. Taylor’s alibis for these journeys were his son and daughter in-law, both of them compromised witnesses, and if the farrier is removed from the barn then so is the blood stick, the weapon that Pierpoint was certain had caused the injuries. Unlike scythes, pitchforks, spades and harrows, blood sticks were not typical agricultural instruments, and there was never any suggestion that Clewes owned one himself. No alternative murder weapon was ever proposed at either the coroner’s inquest or the trial, so if a blood stick was present then it is almost certain a farrier was too.

Banks also declared erroneously that Taylor had no motive to attack Heming, but John Rowe’s evidence shows that before Parker’s murder on Midsummer Day Taylor was already involved in the scheme. He had approached Rowe on behalf of Captain Evans with the offer of £50 so would have had a vested interest in the crime being executed cleanly. When he learnt that Heming had been seen and pursued, he knew he was as exposed as Barnett, Clewes, Banks and the Captain, and if Rowe or anyone else spoke out, equally likely to be arrested as an accessory before the fact. In addition, Clewes asserted that he was only given between £26 and £27 by Banks and Barnett at Pershore Fair on 26 June. If a total of £50 had been originally raised for Heming, what became of the rest? It’s highly likely that the Captain split the blood money between Clewes and Taylor. One paid to keep quiet, the other rewarded for his work.

A third strand of Banks’ defence that can be debunked relates to his allusion to a feud between the Captain and himself. ‘I was driven from Captain Evans’ house by his cruel treatment of me,’ he declared. But this occurred after June 1806 – by Banks’ own admission as much as a year or two later. All other evidence suggests that during the summer of 1806 he remained firmly in the Captain’s favour. And although the rift between the men was certainly deep, by the time of the Captain’s death in June 1829 they had settled their differences. Banks inherited much of the Captain’s estate and had visited him during his last weeks.

There are however elements of Clewes’ confession that are questionable. Clewes’ desperation to absolve himself from any connection to Heming’s murder leaves him looking like that most familiar of judicial paradoxes, the unwilling criminal. John Curwood, the prosecution barrister, had quipped, ‘I never knew an accessory who did not, according to his statement, fill a very insignificant part in the transaction.’ Surely Clewes played a greater role than he admitted? If Clewes had not unlocked the barn, how could Heming had gained entry to the building in the first place? As Charles Burton’s evidence showed, one of the two pairs of double doors was barred by a thick rail and the other secured with a padlock. Also, how did Heming get into the barn without rousing Clewes’ hounds? Then there was the spade – rightly cited by Banks as mysterious. It was possible that it had been brought along by Captain Evans, but Clewes’ outburst, ‘It was no spade of mine,’ seemingly shoehorned into his confession, has an almost exaggerated element of protest about it. Almost as if Clewes was trying too hard to conceal something.

Most peculiar of all was Clewes’ failure to identify the fourth man in the barn. He supposed that it was George Banks, although he would not swear to it. This is difficult to square. With all the details and dialogue of the night so strongly retained in his mind, he must have known who this individual was, but all he would assert in the confession was ‘I thought it be George Banks

5

– I believe it be him.’

To Banks this was a scurrilous falsehood. But why should Clewes place him in the barn if he was not there? Clewes had nothing to gain by doing so and would only incur Banks’ wrath as a result. The only plausible explanation is that Clewes suggested Banks was in the barn because he was. There is evidence that supports this theory very strongly.

This clue is contained in Reverend Clifton’s

6

first letter, written to Robert Peel at the Home Office after Thomas Clewes’ oral confession on Sunday 31 January. Clifton subsequently tried to destroy all traces of this confession, but he had no access to this letter – copied by a clerk in Peel’s Whitehall office – which was released on the declassification of the information decades later. In his letter to Peel, Clifton wrote that Clewes had admitted to being present at Heming’s murder. In addition to him, there were ‘three other persons, two of whom are since dead’. Clifton told Peel that he had already issued a warrant for the arrest of the third person, and he expressed his hope that they should ‘doubtless have him in gaol tonight’. ‘The person whom I have sent to apprehend is the nephew of the man who planned the whole affair, & who assisted to drag the body to the hole in which it was immediately buried in the barn where the murder was committed. The great principal, & the man who struck the blow, by which Heming was killed, are both dead.’

If this small scrap of evidence had been destroyed or lost, then the case against Clewes would be far stronger. As in Clewes’ second confession, the Captain is accused of planning Heming’s murder and Taylor lands the fatal blow. But it is the reference to the ‘nephew of the man who planned the whole affair’ which is interesting. This must be Banks: he was arrested the night that this confession was given amid swirling rumours about his links with Evans, and Clifton must have mistakenly recorded him as the Captain’s son or nephew. The crucial point is that in his first confession Clewes asserted that Banks was present at the murder and taking an active role – dragging the body into the grave.

Therefore, rather than incriminating Banks, the likelihood is that Clewes was actually covering for him. There was little need to shield either Evans or Taylor as they were both dead, but to be vague about both his own and Banks’ roles might just have saved their lives. In this version of events Clewes is not the sly tactician that Peel had him down for; he is a scared and depressed farmer, locked away in a miserable gaol with evidence quickly mounting against him. For years he had been tormented by the events of 25 June 1806, and when Clifton visited him in his cell he told him everything. It is revealing that Clifton, who as a clergyman and magistrate would have conducted many interviews of various types during his life, believed Clewes to be telling the truth. A reasoned guess would also have Clewes, as well as Banks, in a more active role: perhaps unlocking the barn for Heming earlier in the day, providing the lantern and a mattock to break the earth, pointing Evans to the dampest corner and helping George Banks to haul the body across the ground. Such things, however, can never be known.