Dark Entries

Robert Aickman

For

GEORGIA

Dauphine de Lyonnesse

by Richard T. Kelly

Is Robert Fordyce Aickman (1914–81) the twentieth century’s ‘most profound writer of what we call horror stories and he, with greater accuracy, preferred to call strange stories’? Such was the view of Peter Straub, voiced in a discerning introduction to Aickman’s posthumous collection

The Wine-Dark Sea

. If you grant Aickman his characteristic insistence on self-classification within this genre of ‘strange’, then you might say he was in a league of his own (rather as Edgar Allan Poe is the lone and undisputed heavyweight in the field of ‘tales of mystery and imagination’). ‘Horror’, though, is clearly the most compelling genre label that exists on the dark side of literary endeavour. So it might be simplest and most useful to the cause of extending Aickman’s fame if we agree that, yes, he was the finest horror writer of the last hundred years.

So elegantly and comprehensively does Aickman encompass all the traditional strengths and available complexities of the supernatural story that, at times, it’s hard to see how any subsequent practitioner could stand anywhere but in his shadow. True, there is perhaps a typical Aickman protagonist – usually but not always a man, and one who does not fit so well with others, temperamentally inclined to his own company. But Aickman has a considerable gift for putting us stealthily behind the eyes of said protagonist. Having established such identification, the way in which he then builds up a sense of dread is masterly. His construction of sentences and of narrative is patient and finical. He seems always to proceed from a rather grey-toned realism where detail accumulates without fuss, and the recognisable material world appears wholly four-square – until you realise that the narrative has been built as a cage, a kind of personal hell, and our protagonist is walking toward death as if in a dream.

This effect is especially pronounced – Aickman, as it were, preordains the final black flourish – in stories such as ‘Never Visit Venice’ (the title gives the nod) and ‘The Fetch’, whose confessional protagonist rightly judges himself ‘a haunted man’, his pursuer a grim and faceless wraith who emerges from the sea periodically to augur a death in the family. Sometimes, though, to paraphrase John Donne, the Aickman protagonist runs to death just as fast as death can meet him: as in ‘The Stains’, an account of a scholarly widower’s falling in love with – and plunging to his undoing through – a winsome young woman who is, in fact, some kind of dryad.

On this latter score it should be said that, for all Aickman’s seeming astringency, many of his stories possess a powerful erotic charge. There is, again, something dreamlike to how quickly in Aickman an attraction can proceed to a physical expression; and yet he also creates a deep unease whenever skin touches skin – as if desire (and the feminine) are forms of snare, varieties of doom. If such a tendency smacks rather of neurosis, one has to say that this is where a great deal of horror comes from; and Aickman carries off his version of it with great panache, always.

On the flipside of the coin one should also acknowledge Aickman’s refined facility for writing female protagonists, and that the ambience of such tales – the world they conjure, the character’s relations to people and things in that world – is highly distinctive and noteworthy within his

oeuvre

. Aickman’s women are generally spared the sort of grisly fates he reserves for his men, and yet still he routinely leaves us to wonder if they are headed to heaven or hell, if not confined to some purgatory. Among his most admired stories in this line are ‘The Inner Room’ and ‘Into the Wood’, works in which the mystery deepens upon the final sentence.

And lest we forget: Aickman can be very witty, too, even in the midst of mounting horrors, and even if it’s laughter in the dark. English readers in particular tend to chuckle over ‘The Hospice’, the story of a travelling salesman trapped in his worst nightmare of a guesthouse, where the guests are kept in ankle-fetters and the evening meal is served in mountainous indigestible heaps (‘It’s turkey tonight . . .’). In the aforementioned ‘The Fetch’, when our haunted man finally finds himself caged in his Scottish family home, watching the wraith watching him from a perch outdoors up high on a broken wall, he still has time to reflect that ‘such levitations are said to be not uncommon in the remoter parts of Scotland’. This is the sound of a refined intellect, an author amusing both himself and us.

2014 is the centenary of Aickman’s birth and sees him honoured at the annual World Fantasy Convention, the forum where, in 1975, his story ‘Pages from a Young Girl’s Journal’ received the award for short fiction. His cult has been secure since then, and yet those who have newly discovered his rare brilliance have quite often wondered why he is not better known outside the supernatural cognoscenti.

One likely reason is that his body of work is so modestly sized: there are only forty-eight extant ‘strange stories’, and there was never a novel; or, to be precise, the two longer-form Aickmans that have been published –

The Late Breakfasters

in 1964 and

The Model

, posthumously, in 1987 – were fantastical (the latter especially), not to say exquisite, but had nothing overtly eerie or blood-freezing about them. Aickman simply refused to cash in on his most marketable skills as a writer (somewhat to the chagrin of the literary agents who represented him).

He was also a relatively late starter.

We Are for the Dark

, his co-publication with Elizabeth Jane Howard to which they contributed three tales apiece, appeared from Jonathan Cape in 1951; but nothing followed until 1964, with his first discrete collection,

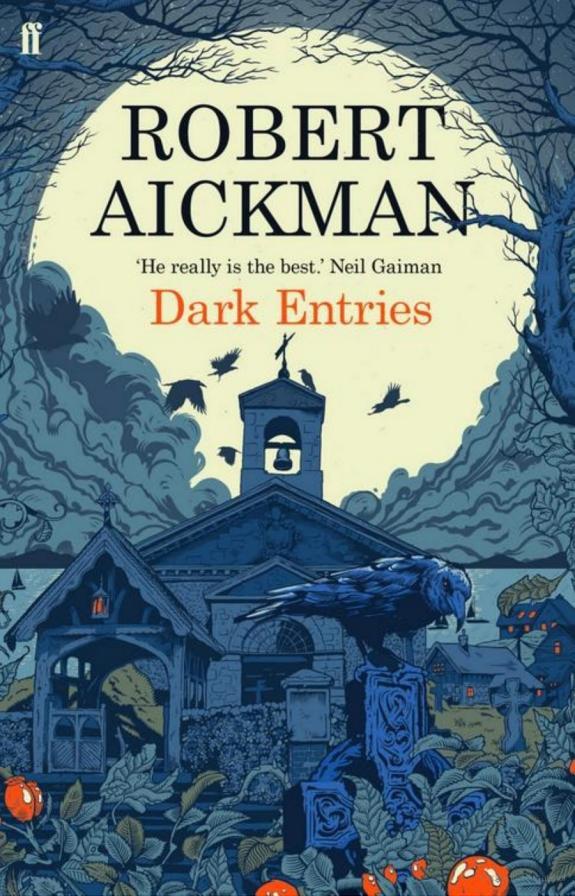

Dark Entries

. By the turn of the 1980s he was a significant figure in the landscape, and from there his renown might have widened. It was then, however, that he developed the cancer from which he would die, on 26 February 1981, having refused chemotherapy in favour of homeopathic treatments.

Aickman’s name would surely enjoy a wider currency today if any of his works had been adapted for cinema, a medium of which he was a discerning fan. And yet, to date, no such adaptation has come about. If we agree that a masterpiece is an idea expressed in its perfect creative form then it may be fair to say that the perfection Aickman achieved in the short story would not suffer to be stretched to ninety minutes or more across a movie screen. But the possibility still exists, for sure. If Aickman made a frightening world all of his own on the page, he also took on some of the great and familiar horror tropes, and treated them superbly.

To wit: the classic second piece in

Dark Entries

, ‘Ringing the Changes’, is a zombie story, immeasurably more ghastly and nerve-straining than

The Walking Dead

. And the aforementioned ‘Pages from a Young Girl’s Journal’ is a vampire story, concerning a pubescent girl bored rigid by her family’s Grand Tour of Italy in 1815, until she is pleasurably transformed by an encounter with a tall, dark, sharp-toothed stranger. In other words it is about the empowering effects of blood-sucking upon adolescent girls; and worth ten of the

Twilight

s of this world. On the strength of such accomplishments one can see that, while Aickman remains for the moment a cult figure, his stories retain the potential to reach many more new admirers far and wide – rather like the vampirised Jonathan Harker at the end of Werner Herzog’s

Nosferatu the Vampyre

(1979), riding out on his steed to infect the world.

Had Aickman never written a word of fiction of his own he would still have a place in the annals of horror: a footnote, perhaps, to observe that he was the maternal grandson of Richard Marsh, bestselling sensational/supernatural novelist of the late-Victorian and Edwardian eras; but an extensive entry for his endeavours as an anthologist who helped to define a canon of supernatural fiction through his editing of the first eight volumes of the

Fontana Book of Great Ghost Stories

between 1964 and 1972.

His enduring reputation, though, would have been based on his co-founding in 1944 of the Inland Waterways Association, dedicated to the preservation and restoration of England’s inland canals. Such a passionate calling might be considered perfect for an author of ‘strange stories’ – also for a man who was, in some profound way, out of step with or apart from his own time. By all accounts Aickman gave the IWA highly energetic leadership and built up its profile and activities with rigour and zeal. His insistent style, however, did not delight everyone: in 1951 he argued and fell out definitively with L. T. C. (Tom) Rolt, fellow conservationist and author, whose seminal book

Narrow Boat

(1944) had inspired the organisation’s founding in the first place.

When we admire a writer we naturally wish to know more of what they were like as a person. Aickman’s admirers have sometimes found what they have heard of him to be a shade forbidding. Culturally he was a connoisseur who had highly finessing tastes in theatre, ballet, opera and classical music. Socially he was punctilious and fastidious, unabashedly erudite, an autodidact not shy about airing his education. His political instincts were conservative, his outlook elitist. The late Elizabeth Jane Howard – first secretary of the Inland Waterways Association, with whom Aickman fell in love and for whom he carried a torch years after her ending of their brief relationship – would tell an interviewer some years later that there were at least two sides to the man: ‘He could be very prickly and difficult, or he could be very charming.’

Nonetheless, those whom Aickman allowed to know him well and whom he liked and trusted in turn clearly found him to be the most marvellous company – for a night at the theatre, say, or a visit to a rural stately home, or at a catered dinner

à deux

, after which he would be inclined to read aloud from whichever strange story he was then working on. The reader will learn more in this line from the afterwords to this series of Faber reissues, which have been written by admiring friends who had just such a privileged insight into the author.

These reissues are in honour of Aickman’s 2014 centenary. Along with the present volume, readers may choose from

Cold Hand in Mine

, the posthumously published compilations

The Unsettled Dust

and

The Wine-Dark Sea

, and (as Faber Finds)

The Late Breakfasters

and

The Model

. Whether these works are already known to you or you are about to discover them, the injunction is the same – prepare to be entranced, compelled, seduced, petrified.

RICHARD T. KELLY

is the author of the novels

Crusaders

and

The Possessions of Doctor Forrest.

‘To be taken advantage of is every woman’s secret wish.’

Princess Elizabeth Bibesco

It would be false modesty to deny that Sally Tessler and I were the bright girls of the school. Later it was understood that I went more and more swiftly to the bad; but Sally continued being bright for some considerable time. Like many males, but few females, even among those inclined to scholarship, Sally combined a true love for the Classics, the ancient ones, with an insight into mathematics which, to the small degree that I was interested, seemed to me almost magical. She won three scholarships, two gold medals, and a sojourn among the Hellenes with all expenses paid. Before she had graduated she had published a little book of popular mathematics which, I understood, made her a surprising sum of money. Later she edited several lesser Latin authors, published in editions so small that they can have brought her nothing but inner satisfaction.

The foundations of all this erudition had almost certainly been laid in Sally’s earliest childhood. The tale went that Dr Tessler had once been the victim of some serious injustice, or considered that he had: certainly it seemed to be true that, as his neighbours put it, he ‘never went out’. Sally herself once told me that she not only could remember nothing of her mother, but had never come across any trace or record of her. From the very beginning Sally had been brought up, it was said, by her father alone. Rumour suggested that Dr Tessler’s regimen was three-fold: reading, domestic drudgery, and obedience. I deduced that he used the last to enforce the two first: when Sally was not scrubbing the floor or washing up, she was studying Vergil and Euclid. Even then I suspected that the Doctor’s ways of making his will felt would not have borne examination by the other parents.

Certainly, however, when Sally first appeared at school, she had much more than a grounding in almost every subject taught, and in several which were not taught. Sally, therefore, was from the first a considerable irritant to the mistresses. She was always two years or more below the average age of her form. She had a real technique of acquiring knowledge. She respected learning in her preceptors, and detected its absence . . . I once tried to find out in what subject Dr Tessler had obtained his doctorate. I failed; but, of course, one then expected a German to be a doctor.

It was the first school Sally had attended. I was a member of the form to which she was originally assigned; but in which she remained for less than a week, so eclipsing to the rest of us was her mass of information. She was thirteen years and five months old at the time; nearly a year younger than I. (I owe it to myself to say that I was promoted at the end of the term; and thereafter more or less kept pace with the prodigy, although this, perhaps, was for special reasons.) Her hair was remarkably beautiful; a perfect light blonde, and lustrous with brushing, although cut short and ‘done’ in no particular way, indeed usually very untidy. She had dark eyes, a pale skin, a large distinguished nose, and a larger mouth. She had also a slim but precocious figure, which later put me in mind of Tessa in

The Constant Nymph

. For better or for worse, there was no school uniform, and Sally invariably appeared in a dark-blue dress of foreign aspect and extreme simplicity, which none the less distinctly became her looks. As she grew, she seemed to wear later editions of the same dress, new and enlarged, like certain publications.

Sally, in fact, was beautiful; but one would be unlikely ever to meet another so lovely who was so entirely and genuinely unaware of the fact and of its implications. And, of course, her casualness about her appearance, and her simple clothes, added to her charm. Her disposition seemed kindly and easy-going in the extreme; and her voice was lazy to drawling. But Sally, none the less, seemed to live only in order to work; and, although I was, I think, her

closest friend (it was the urge to keep up with her which explained much of my own progress in the school), I learnt very little about her. She seemed to have no pocket-money at all: as this amounted to a social deficiency of the vastest magnitude, and as my parents could afford to be and were generous, I regularly shared with her. She accepted the arrangement simply and warmly. In return she gave me frequent little presents of books: a copy of Goethe’s

Faust

in the original language and bound in somewhat discouraging brown leather; and an edition of Petronius, with some remarkable drawings . . . Much later, when in need of money for a friend, I took the

Faust

, in no hopeful spirit, to Sotheby’s. It proved to be a rebound first edition . . .

But it was a conversation about the illustrations in the Petronius (I was able to construe Latin fairly well for a girl, but the italics and long s’s daunted me) which led me to the discovery that Sally knew more than any of us about the subject illustrated. Despite her startling range of information she seemed then, and certainly for long after, completely disinterested in any personal way. It was as if she discoursed, in the gentlest, sweetest manner, about some distant far-off thing, or, to use a comparison absurdly hackneyed but here appropriate, about botany. It was an ordinary enough school, and sex was a preoccupation among us. Sally’s attitude was surprisingly new and unusual. In the end she did ask me not to tell the others what she had just told me.

‘As if I would,’ I replied challengingly, but still musingly.

And in fact I didn’t tell anyone until considerably later: when I found that I had learned from Sally things which no one else at all seemed to know; things which I sometimes think have in themselves influenced my life, so to say, not a little. Once I tried to work out how old Sally was at the time of this conversation. I think she could hardly have been more than fifteen.

*

In the end Sally won her university scholarship, and I

just failed, but won the school’s English Essay Prize, and also the Good Conduct Medal, which I deemed (and still deem) in

the nature of a stigma, but believed, consolingly, to be awarded more to my prosperous father than to me. Sally’s conduct was in any case much better than mine, being indeed irreproachable. I had entered for the scholarship with the intention of forcing the examiners, in the unlikely event of my winning it, to bestow it upon Sally, who really needed it. When this doubtless impracticable scheme proved unnecessary, Sally and I parted company, she to her triumphs of the intellect, I to my lesser achievements. We corresponded intermittently, but decreasingly as our areas of common interest diminished. Ultimately, for a very considerable time, I lost sight of her altogether, although occasionally over the years I used to see reviews of her learned books, and encounter references to her in leading articles about the Classical Association and similar indispensable bodies. I took it for granted that by now we should have difficulty in communicating at all. I observed that Sally did not marry. One couldn’t wonder, I foolishly and unkindly drifted into supposing . . .

When I was forty-one, two things happened which have a bearing on this narrative. The first was that a catastrophe befell me which led to my again taking up residence with my parents. Details are superfluous. The second thing was the death of Dr Tessler.

I should probably have heard of Dr Tessler’s death in any case, for my parents, who, like me and the rest of the neighbours, had never set eyes upon him, had always regarded him with mild curiosity. As it was, the first I knew of it was when I saw the funeral. I was shopping on behalf of my mother, and reflecting upon the vileness of things, when I observed old Mr Orbit remove his hat, in which he always served, and briefly sink his head in prayer. Between the aggregations of Shredded Wheat in the window, I saw the passing shape of a very old-fashioned and therefore very ornate horse-drawn hearse. It bore a coffin covered in a pall

of worn purple velvet; but there seemed to be no mourners at all.

‘Didn’t think never to see a ’orse ’earse again, Mr Orbit,’ remarked old Mrs Rind, who was ahead of me in the queue.

‘Pauper funeral, I expect,’ said her friend old Mrs Edge.

‘No such thing no more,’ said Mr Orbit quite sharply, and replacing his hat. ‘That’s Dr Tessler’s funeral. Don’t suppose ’e ’ad no family come to look after things.’

I believe the three white heads then got together, and began to whisper; but, on hearing the name, I had made towards the door. I looked out. The huge ancient hearse, complete with vast black plumes, looked much too big for the narrow autumnal street. It put me in mind of how toys are often so grossly out of scale with one another. I could now see that instead of mourners, a group of urchins, shadowy in the fading light, ran behind the bier, shrieking and jeering: a most regrettable scene in a well-conducted township.

For the first time in months, if not years, I wondered about Sally.

Three days later she appeared without warning at my parents’ front door. It was I who opened it.

‘Hallo, Mel.’

One hears of people who after many years take up a conversation as if the same number of hours had passed. This was a case in point. Sally, moreover, looked almost wholly unchanged. Possibly her lustrous hair was one half-shade darker, but it was still short and wild. Her lovely white skin was unwrinkled. Her large mouth smiled sweetly but, as always, somewhat absently. She was dressed in the most ordinary clothes, but still managed to look like anything but a don or a dominie: although neither did she look like a woman of the world. It was, I reflected, hard to decide what she did look like.

‘Hallo, Sally.’

I kissed her and began to condole.

‘Father really died before I was born. You know that.’

‘I have heard something.’ I should not have been sorry

to hear more; but Sally threw off her coat, sank down before the fire, and said:

‘I’ve read all your books. I loved them. I should have written.’

‘Thank you,’ I said. ‘I wish there were more who felt like you.’

‘You’re an artist, Mel. You can’t expect to be a success at the same time.’ She was warming her white hands. I was not sure that I was an artist, but it was nice to be told.

There was a circle of leather-covered armchairs round the fire. I sat down beside her. ‘I’ve read about you often in the

Times

Lit

,’ I said, ‘but that’s all. For years. Much too long.’

‘I’m glad you’re still living here,’ she replied.

‘Not

still.

Again.’

‘Oh?’ She smiled in

her gentle, absent way.

‘Following a session in the frying-pan, and another one in the fire . . . I’m sure you’ve been conducting yourself more sensibly.’ I was still fishing.

But all she said was, ‘Anyway I’m still glad you’re living here.’

‘Can’t say

I

am. But why in particular?’

‘Silly Mel! Because I’m going to live here too.’

I had never even thought of it.

I could not resist a direct question.

‘Who told you your father was ill?’

‘A friend. I’ve come all the way from Asia Minor. I’ve been looking at potsherds.’ She was remarkably untanned for one who had been living under the sun; but her skin was of the kind which does not tan readily.

‘It will be lovely to have you about again. Lovely, Sally. But what will you do here?’

‘What do

you

do?’

‘I write . . . In other ways my life is

rather over, I feel.’

‘

I

write too. Sometimes. At least I edit . . . And I don’t think my life, properly speaking, has ever begun.’

I had spoken in self-pity, although I had not wholly meant to do so. The tone of her reply I found it impossible to

define. Certainly, I thought with slight malice, certainly she does look absurdly virginal.

*

A week later a van arrived at Dr Tessler’s house, containing a great number of books, a few packed trunks, and little else; and Sally moved in. She offered no further explanation for this gesture of semi-retirement from the gay world (for we lived about forty miles from London, too many for urban participation, too few for rural self-sufficiency); but it occurred to me that Sally’s resources were doubtless not so large that she could disregard an opportunity to live rent-free, although I had no idea whether the house was freehold, and there was no mention even of a will. Sally was and always had been so vague about practicalities, that I was a little worried about these matters; but she declined ideas of help. There was no doubt that if she were to offer the house for sale, she could not expect from the proceeds an income big enough to enable her to live elsewhere; and I could imagine that she shrank from the bother and uncertainty of letting.

I heard about the contents of the van from Mr Ditch, the remover; and it was, in fact, not until she had been in residence for about ten days that Sally sent me an invitation. During this time, and after she had refused my

help with her affairs, I had thought it best to leave her alone. Now, although the house which I must thenceforth think of as hers stood only about a quarter of a mile from the house of my parents, she sent me a postcard. It was a picture postcard of Mitylene. She asked me to tea.

The way was through the avenues and round the corners of a mid-nineteenth-century housing estate for merchants and professional men. My parents’ house was intended for the former; Sally’s for the latter. It stood, in fact, at the very end of a cul-de-sac: even now the house opposite bore the plate of a dentist.

I had often stared at the house during Dr Tessler’s occupancy, and before I knew Sally; but not until that day did I enter it.

The outside looked much as it had ever done. The house was built in a grey brick so depressing that one

speculated how anyone could ever come to choose it (as many once did, however, throughout the Home Counties). To the right of the front door (approached by twelve steps, with blue and white tessellated risers) protruded a greatly disproportionate obtuse-angled bay window: it resembled the thrusting nose on a grey and wrinkled face. This bay window served the basement, the ground floor, and the first floor: between the two latter ran a dull red string course ‘in an acanthus pattern’, like a chaplet round the temples of a dowager. From the second-floor window it might have been possible to step on to the top of the projecting bay, the better to view the surgery opposite; had not the second-floor window been barred, doubtless as protection for a nursery. The wooden gate had fallen from its hinges, and had to be lifted open and shut. It was startlingly heavy.