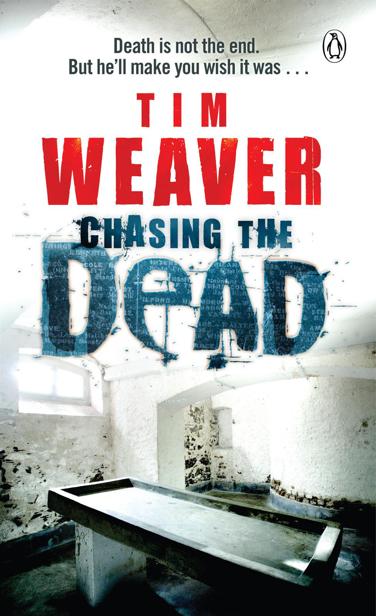

David Raker 01 - Chasing the Dead

Read David Raker 01 - Chasing the Dead Online

Authors: Tim Weaver

PENGUIN BOOKS

Chasing the Dead

Tim Weaver was born in 1977. He left school at eighteen and started working in magazine journalism, and has since gone on to develop a successful career writing about films, TV, sport, games and technology. He is married with a young daughter, and lives near Bath.

Chasing the Dead

is his first novel.

TIM WEAVER

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKSPENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London

WC2R 0RL

, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario,

Canada

M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland

(a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell,

Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd,

11

Community Centre,

Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632,

New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London

WC2R 0RL

, England

First published 2010

Copyright © Tim Weaver, 2010

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-0-14-194374-9

and every living soul died in the sea’

Revelation 16:3

Sometimes, towards the end, she would wake me by tugging at the cusp of my shirt, her eyes moving like marbles in a jar, her voice begging me to pull her to the surface. I always liked that feeling, despite her suffering, because it meant she’d lasted another day.

Her skin was like canvas in those last months, stretched tight against her bones. She’d lost all her hair as well, except for some bristles around the tops of her ears. But I never cared about that; about any of it. If I’d been given a choice between having Derryn for a day as she was when I’d first met her, or having her for the rest of my life as she was at the end, I would have taken her as she was at the end, without even pausing for thought. Because, in the moments when I thought about a life without her, I could barely even breathe.

She was thirty-two, seven years younger than me, when she first found the lump. Four months later, she collapsed in the supermarket. I’d been a newspaper journalist for eighteen years but, after it happened a second time on the Underground, I resigned, went freelance and refused to travel. It wasn’t a hard decision. I didn’t want to be on the other side of the world when the third call came through telling me this time she’d fallen and died.

When it became clear the chemotherapy wasn’t working, she decided to stop. I cried that day,

really

cried, probably for the first time since I was a kid. But – looking back – she made the right decision. She still had some dignity. Without hospital visits and the time it took her to recover from them, our lives became more spontaneous, and that was an exciting way to live for a while. She read a lot and she sewed, and I did some work on the house, painting walls and fixing rooms. And a month after she stopped her chemo, I started to plough some money into creating a study. As Derryn reminded me, I’d need a place to work.

Except the work never came. There was a little – sympathy commissions mostly – but my refusal to travel turned me into a last resort. I’d become the type of freelancer I’d always loathed. I didn’t want to be that person, was even conscious of it happening. But at the end of every day Derryn became a little more important to me, and I found that difficult to let go.

Then one day I got home and found a letter on the living-room table. It was from one of Derryn’s friends.

So I said no. But, when I took the letter through to the back garden, Derryn was gently rocking in her chair with the tiniest hint of a smile on her face.

‘What’s so funny?’

‘You’re not sure if you should do it.’

‘I’m sure,’ I said. ‘I’m sure I

shouldn’t

do it.’

She nodded.

‘Do you think I should do it?’

‘It’s perfect for you.’

‘What, chasing after missing kids?’

‘It’s

perfect

for you,’ she said. ‘Take this chance, David.’

And that was how it began.

I pushed the doubt down with the sadness and the anger and found the girl three days later in a bedsit in Walthamstow. Then, more work followed, more missing kids, and I could see the ripples of the career I’d left behind coming back again. Asking questions, making calls, trying to pick up the trail. I’d always liked the investigative parts of journalism, the dirty work, the digging,

But despite the hundreds of kids that went missing every day of every year, I’m not sure I ever expected to make a living out of trying to find them. It never felt like a job; not in the way journalism had. And yet, after a while, the money really started coming in. Derryn persuaded me to rent some office space down the road from our home, in an effort to get me out, but also – more than that, I think – to convince me I could make a career out of what I was doing. She called it a long-term plan.

Two months later, she died.

When I opened the door to my office, it was cold and there were four envelopes on the floor inside. I tossed the mail on to the desk and opened the blinds. Morning light erupted in, revealing photos of Derryn everywhere. In one, my favourite, we were in a deserted coastal town in Florida, sand sloping away to the sea, jellyfish scattered like cellophane across the beach. In the fading light, she looked beautiful. Her eyes flashed blue and green. Freckles were scattered along her nose and under the curve of her cheekbones. Her blonde hair was bleached by the sun, and her skin had browned all the way up her arms.

I sat down at my desk and pulled the picture towards me.

Next to her, my eyes were dark, my hair darker, stubble lining the ridge of my chin and the areas around my mouth. I towered over her at six-two. In the picture, I was pulling her into me, her head resting against the muscles in my arms and chest, her body fitting in against mine.

Physically, I’m the same now. I work out when I can. I take pride in my appearance. I still want to be attractive. But maybe, temporarily, some of the lustre has rubbed away. And, like the parents of the people I trace, some of the spark in my eyes too.

Their faces filled an entire corkboard on the wall behind me. Every space. Every corner. There were no pictures of Derryn behind my desk.

Only pictures of the missing.

After I found the first girl, her mother put up a notice; to start with, on the board in the hospital ward where she worked with Derryn, and then in some shop windows, with my name and number and what I did. I think she felt sorry at the thought of me – somewhere along the line – being on my own. Sometimes, even now, people would call me, asking for my help, telling me they’d seen an advert in the hospital. And I guess I liked the idea of it still being there. Somewhere in that labyrinth of corridors, or burnt yellow by the sun in a shop window. There was a symmetry to it. As if Derryn still somehow lived on in what I did.

I spent most of the day sitting at my desk with the lights off. The telephone rang a couple of times, but I left it, listening to it echo around the office. A year ago, to the day, Derryn had been carried out of our house on a stretcher. She’d died seven hours later. Because of that, I knew I wasn’t in the right state of mind to consider taking on any work, so when the clock hit four, I started to pack up.

That was when Mary Towne arrived.

I could hear someone coming up the stairs, slowly taking one step at a time. Eventually the top door

‘Hi, Mary.’

I startled her. She looked up. Her skin was darkened by creases, every one of her fifty years etched into her face. She must have been beautiful once, but her life had been pushed and pulled around and now she wore the heartache like an overcoat. Her small figure had become slightly stooped. The colour had started to drain from her cheeks and her lips. Thick ribbons of grey had begun to emerge from her hairline.

‘Hello, David,’ she said quietly. ‘How are you?’

‘Good.’ I shook her hand. ‘It’s been a while.’

‘Yes.’ She looked down into her lap. ‘A year.’

She meant Derryn’s funeral.

‘How’s Malcolm?’

Malcolm was her husband. She glanced at me and shrugged.

‘You’re a long way from home,’ I said.

‘I know. I needed to see you.’

‘Why?’

‘I wanted to discuss something with you.’

I tried to imagine what.

‘I couldn’t get you on the telephone.’

‘No.’

‘It’s kind of a…’ I looked back to my office. To the pictures of Derryn. ‘It’s kind of a difficult time for me at the moment. Today, in particular.’

She nodded. ‘I know it is. I’m sorry about the timing, David. It’s just… I know you care about what you’re doing. This job. I need someone like that. Someone who cares.’ She glanced at me again. ‘That’s why people like you. You understand loss.’

‘I’m not sure you ever understand loss.’ I looked up, could see the sadness in her face, and wondered where this was going. ‘Look, Mary, at the moment I’m not tracing anything – just the lines on my desk.’

She nodded once more. ‘You remember what happened to Alex?’

Alex was her son.

‘Of course.’

‘You remember all the details?’

‘Most of them.’

‘Would you mind if I went back over them?’ she asked.

I paused, looked at her.

‘

Please

.’

I nodded. ‘Why don’t we go through?’

I led her out of the waiting area and back to my desk. She looked around at the photos on the walls, her eyes moving between them.