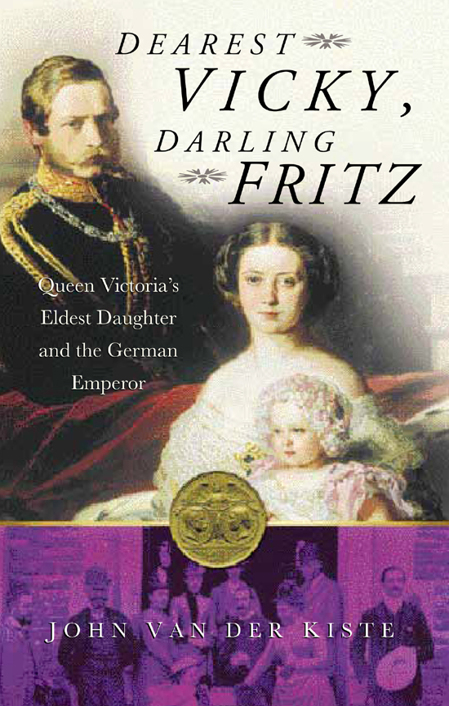

Dearest Vicky, Darling Fritz

Read Dearest Vicky, Darling Fritz Online

Authors: John Van der Kiste

D

EAREST

V

ICKY

,

D

ARLING

F

RITZ

The Tragic Love Story of

Queen Victoria’s Eldest Daughter

and the German Emperor

J

OHN

V

AN

DER

K

ISTE

First published in 2001

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire,

GL

5 2

QG

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© John Van der Kiste, 2001, 2013

The right of John Van der Kiste to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB

ISBN

978 0 7524 9926 0

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

Sources and Acknowledgements

V

icky has attracted several biographers, from the anonymous writer (believed to be Marie Belloc Lowndes) of the authoritative

The Empress Frederick: a Memoir

(1913), her friend Princess Catherine Radziwill (1934), and a rather emotional, unsympathetic account by E.E.P. Tisdall (1940), to more recent studies by Richard Barkeley (1956), Egon Conte Caesar Corti (1957), Daphne Bennett (1971), Andrew Sinclair (1981) and Hannah Pakula (1996).

Fritz has fared less well. Within three years there were two biographies, a short volume by Rennell Rodd (1888) and a more extensive one by Lucy Taylor (1891). Apart from a few titles published only in Germany, there were no works in English between a one-volume English translation of Margaretha von Poschinger’s three-volume life edited by Sidney Whitman (1901) and one by the present author (1981). A more recent study by Patricia Kollander (1995), a political rather than personal life, has necessitated a re-evaluation of his liberal principles, which in her view have been rather exaggerated. To these may be added a dual biography of both published during their lifetime, by Dorothea Roberts (1887), which is naturally incomplete but still useful within its limitations.

These have been supplemented by a valuable series of correspondence and diaries. The Empress’s letters to and from Queen Victoria have been edited successively by Roger Fulford and Agatha Ramm in six volumes, supplementing two earlier works, the controversial, largely political

Letters of the Empress Frederick

, edited by her godson Sir Frederick Ponsonby (1928) and the more personal

The Empress Frederick writes to Sophie

, edited by Arthur Gould Lee (1955). Selections from the Emperor’s diaries have been published in English translation, notably his ‘war diary’ kept during the Franco-Prussian campaign, and those describing his travels to the east and to Spain.

I wish to acknowledge the gracious permission of Her Majesty The Queen to publish certain letters of which she owns the copyright, and others which are held in the Royal Archives, Windsor. For permission to publish the latter I wish to acknowledge the gracious permission of Prince Moritz, Landgraf von Hessen, as representative of the owners of copyright in the Empress Frederick’s letters. I am also indebted to the India Office Library, British Museum, for permission to publish extracts from correspondence between the Emperor, Empress, and Count Seckendorff with Baron Napier of Magdala.

I am grateful to the following publishers for permission to quote from printed sources: Cambridge University Press (

Young Wilhelm

, by John Röhl, © 1998;

The Holstein Papers

, edited by Norman Rich & M.H. Fisher, © 1955–63); Cassell Ltd (

The English Empress

, Conte Egon Caesar Corti, © 1957); and Greenwood Press (

Frederick III, Germany’s liberal Emperor

, by Patricia Kollander, © 1995).

As ever I am eternally grateful to various friends for their moral support, advice and loan of various materials while writing this book, especially Karen Roth, Sue Woolmans, Theo Aronson, Dale Headington, and Robin Piguet; to the staff of Kensington and Chelsea Public Libraries, for ready access to their reserve collection; to my editors, Jaqueline Mitchell and Paul Ingrams. Last but not least, my mother, Kate Van der Kiste, has as always been a tower of strength in discussions on the subject and in reading through the draft manuscript.

T

HE

H

OUSE

OF

H

OHENZOLLERN

T

HE

H

OUSE

OF

S

AXE

-C

OBURG

G

OTHA

Introduction

O

n 25 January 1858 ‘Vicky’, Princess Royal, eldest daughter of Queen Victoria and Albert, Prince Consort, of England married ‘Fritz’, Prince Friedrich Wilhelm, second in succession to the throne of Prussia. London sparkled with illuminations in her public buildings and firework displays in her grand parks. The festivities spread far beyond the centre of the capital as the whole nation went

en fête

for ‘England’s Daughter’ and her husband, with gifts and public dinners for the needy in cities up and down the country.

Having made their responses ‘very

plainly

’, in Queen Victoria’s words, at the altar in the chapel of St James’s, Vicky and Fritz walked hand in hand to the vestry to join the rest of the family for the signing of the marriage register, full of confidence and beaming at the assembled guests. Before the wedding breakfast they stepped out on to the balcony at Buckingham Palace, to be cheered by the crowds in Pall Mall who had braved the winter cold for a glimpse of the Royal couple. They may have been overwhelmed by this reception, conscious of the fact that they were carrying the hopes of a generation; but they were deliriously happy nonetheless. When bride and groom reached Windsor later that day they were met by yet more fireworks, a guard of honour, and a crowd of boys from Eton College who pulled their carriage from the railway station uphill to the castle. It was a heady start to one of the great love matches of its time.

Historians and biographers have never doubted that it was, in personal terms, an extremely successful marriage. Thirteen years later, a political union was achieved; but it was neither the united constitutional or liberal power that they and their elders had envisaged. Within less than five years of the wedding, two events occurred which were to shake the destiny of the young couple to its very core: firstly, the unexpected death of their mentor, Vicky’s father, Prince Albert; and secondly, the appointment of Count Otto von Bismarck as Minister-President of Prussia. Ultimately, Vicky and Fritz were to be eclipsed by the ambitions of their eldest son, Wilhelm, and by the eventual failure of the hoped-for alliance which would later disintegrate into the carnage and confusion of the First World War.

Personal factors apart, the marriage had begun with high hopes. It was a truly grand dynastic alliance between the Hohenzollerns of Prussia and Queen Victoria’s family of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, later the House of Windsor, intended to bring to fruition the vision of Prince Albert and his mentors, King Leopold of the Belgians and Baron Christian von Stockmar, of a united, liberal and constitutional Germany. This was to be led by Prussia, with King Friedrich Wilhelm and his consort, a ‘second’ Queen Victoria, at the helm. At the same time as it was intended to fulfil this high-minded ambition, however, theirs was undeniably a genuine love match. For, in the annals of nineteenth century history, Vicky and Fritz were almost uniquely well-suited. She was a charming, bubbly, naïve child of seventeen; he a handsome, chivalrous, yet somewhat withdrawn and self-effacing young man of twenty-six. They had been besotted with one another since their betrothal a little over two years before, and were to remain passionately in love for thirty more years.