Decoded (19 page)

Authors: Jay-Z

Tags: #Rap & Hip Hop, #Rap musicians, #Rap musicians - United States, #Cultural Heritage, #Jay-Z, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Music, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Composers & Musicians, #Biography

“I

f you’re proud to be an American, put your hands up now!” It was the night after the inauguration and I was in Washington, D.C., playing a free show for ten thousand Obama for America volunteers. It was the cap of a euphoric and surreal few months, when the entire history of the world that I’d known up to that point totally flipped. The words “proud to be an American” were not words I’d ever thought I’d say. I’d written America off, at least politically.

Of course, it’s my home, and home to millions of people trying to do the right thing, not to mention the home of hip-hop, Quentin Tarantino flicks, the crossover dribble and lots of other things I couldn’t live without. But politically, its history is a travesty. A graveyard. And I knew some of the bodies it buried.

It never seemed as hopeless as it was during the eight years that preceded that night in Washington. I was so over America that if John McCain and Sarah Palin had won that election I was seriously ready to pack up, get some land in some other country, and live as an expat in protest. The idea of starting a show that way would’ve been, at any other time in my entire life up to that point, completely perverse. Because America, as I understood the concept, hated my black ass.

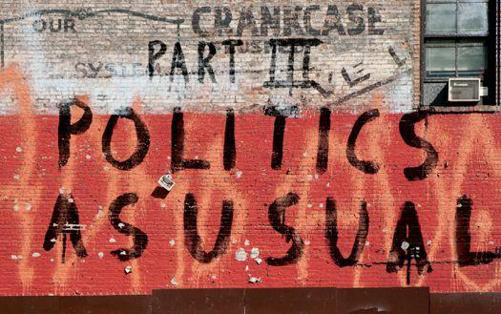

FUCK GOVERNMENT, NIGGAS POLITIC THEMSELVES

Poor people in general have a twisted relationship with the government. We’re aware of the government from the time we’re born. We live in government-funded housing and work government jobs. We have family and friends spending time in the ultimate public housing, prison. We grow up knowing people who pay for everything with little plastic cards—Medicare cards for checkups, EBT cards for food. We know what AFDC and WIC stand for and we stand for hours waiting for bricks of government cheese. The first and fifteenth of each month are times of peak economic activity. We get to know all kinds of government agencies not because of civics class, but because they actually visit our houses and sit up on our couches asking questions. From the time we’re small children we go to crumbling public schools that tell us all we need to know about what the government thinks of us.

Then there are the cops.

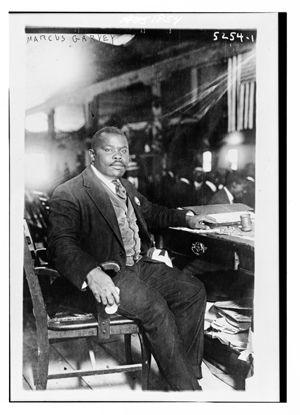

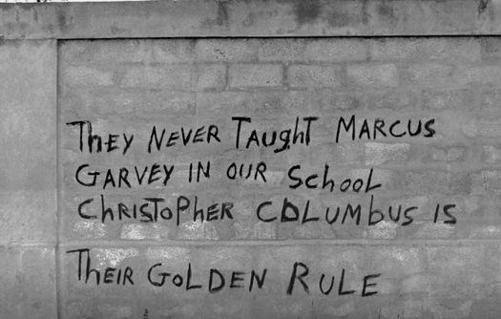

In places like Marcy there are people who know the ins and outs of government bureaucracies, police procedures, and sentencing guidelines, who spend half of their lives in dirty waiting rooms on plastic chairs waiting for someone to call their name. But for all of this involvement, the government might as well be the weather because a lot of us don’t think we have anything to do with it—we don’t believe we have any control over this thing that controls us. A lot of our heroes, almost by default, were people who tried to dismantle or overthrow the government—Malcolm X or the Black Panthers—or people who tried to make it completely irrelevant, like Marcus Garvey, who wanted black people to sail back to Africa. The government was everywhere we looked, and we hated it.

Housing projects are a great metaphor for the government’s relationship to poor folks: these huge islands built mostly in the middle of nowhere, designed to warehouse lives. People are still people, though, so we turned the projects into real communities, poor or not. We played in fire hydrants and had cookouts and partied, music bouncing off concrete walls. But even when we could shake off the full weight of those imposing buildings and try to just live, the truth of our lives and struggle was still invisible to the larger country. The rest of the country was freed of any obligation to claim us. Which was fine, because we weren’t really claiming them, either.

CAN’T SEE THE UNSEEABLE, REACH THE UNREACHABLE

Hip-hop, of course, was hugely influential in finally making our slice of America visible through our own lens—not through the lens of outsiders. But it wasn’t easy.

There are all the famous incidents of censorship and intimidation: the way politicians attacked rappers, the free-speech cases with groups like Two Live Crew, the dramas surrounding Public Enemy and political rap, the threatening letters from the FBI protesting NWA. But the attempts at censorship only made the targets bigger stars. NWA couldn’t have bought the kind of publicity they got from having

the actual fucking FBI

attacking them over a song. This was when you had one prominent Harlem pastor renting a bulldozer and calling news cameras to film him running over a pile of rap CDs in the middle of 125th Street. When WBLS, a legendary black-owned radio station in New York, stripped hip-hop from their playlists in sympathy with the protest, another radio station, Hot 97, came along with an

all-rap

format and went straight to number one. In a few years, WBLS came back to rap. In the end, you can’t censor the truth, especially when it comes packaged in hot music.

Those battles were big for all of us in hip-hop and offered an important survival lesson: Politicians—at the highest levels—would try to silence and kill our culture if they could hustle some votes out of it. Even black leaders who were supposed to be representing you would turn on you—would pile your records up and run over them with a fucking bulldozer or try to ban you from radio—if they felt threatened by your story or language. But the thing is, we kept winning.

The push for censorship only reinforced what most of us already suspected: America doesn’t want to hear about it. There was a real tension between the power of the story we wanted to tell and just how desperately some powerful people didn’t want to hear it. But the story had to come out sooner or later because it was so dramatic, important, crazy—and just plain compelling.

Back in the eighties and early nineties cities in this country were literally battlegrounds. Kids were as well armed as a paramilitary outfit in a small country. Teenagers had Uzis, German Glocks, and assault rifles—and we had the accessories, too, like scopes and silencers. Guns were easier to get in the hood than public assistance. There were times when the violence just seemed like background music, like we’d all gone numb.

The deeper causes of the crack explosion were in policies concocted by a government that was hostile to us, almost genocidally hostile when you think about how they aided or tolerated the unleashing of guns and drugs on poor communities, while at the same time cutting back on schools, housing, and assistance programs. And to top it all off, they threw in the so-called war on drugs, which was really a war on us. There were racist new laws put on the books, like the drug laws that penalized the possession of crack cocaine with more severe sentences than the possession of powder. Three-strike laws could put young guys in jail for twenty-five years for nonviolent crimes. The disease of addiction was treated as a crime. The rate of incarceration went through the roof. Police abuses and corruption were rampant. Across the country, cops were involved in the drug trade, playing both sides. Young black men in New York in the eighties and nineties were gunned down by cops for the lightest suspected offenses, or died in custody under suspicious circumstances. And meanwhile we were killing ourselves by the thousands.

Almost twenty years after the fact, there are studies that say between 1989 and 1994 more black men were murdered in the streets of America than died in the entire Vietnam War. America did not want to talk about the human damage, or the deeper causes of the carnage. But then here came rap, like the American nightmare come to life. The disturbing shit you thought you locked away for good, buried at the bottom of the ocean, suddenly materialized in your kid’s bedroom, laughing it off, cursing loud, and grabbing its nuts, refusing to be ignored anymore.

I’m America’s worst nightmare / I’m young black and holding my nuts like shh-yeah.

Hardcore rap wasn’t political in an explicit way, but its volume and urgency kept a story alive that a lot of people would have preferred to disappear. Our story. It scared a lot of people.

WE TOTE GUNS TO THE GRAMMYS

Invisibility was the enemy, and the fight had multiple fronts. For instance, 1998 was an important year for hip-hop. It was two years after Pac had been gunned down, and just a year after Biggie was killed. DMX dropped two number one albums that year. Outkast released

Aquemini,

a game-changing album lyrically and sonically, but also for what it meant to Southern rap. (Juvenile’s

400 Degreez,

also released in ’98, was a major shot in the growing New Orleans movement. I jumped on a remix of his single “Ha,” which was a great mix of regional styles.) Mos Def and Talib Kweli had their Black Star album, one of the definitive indie rap records of all time. The prototypical “backpack rappers,” A Tribe Called Quest, released their last album,

The Love Movement.

And the biggest album of the year in any genre was

The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill.

It was a beautiful time all the way around in hip-hop. The album I released that year,

Vol. 2 … Hard Knock Life,

was the biggest record of my life. The opening week was unreal for me—we did more than three hundred thousand units, by far the biggest opening number of my career to that point. The album moved Lauryn Hill down to number four, but Outkast’s

Aquemini

was right behind me, and

The Love Movement

was number three. Those four albums together told the story of young black America from four dramatically different perspectives—we were bohemians and hustlers and revolutionaries and space-age Southern boys. We were funny and serious, spiritual and ambitous, lovers and gangsters, mothers and brothers. This was the full picture of our generation. Each of these albums was an innovative and honest work of art and wildly popular on the charts. Every kid in the country had at least one of these albums, and a lot of them had all four. The entire world was plugged into the stories that came out of the specific struggles and creative explosion of our generation. And that was just the tip of the iceberg of what was happening in hip-hop that year.

So, in this incredible year for diverse strands of real hip-hop, what happens at the Grammy Awards? First, DMX, with two number one albums and a huge single, “Get at Me Dog,” that brought rap back to its grimy roots, was completely snubbed. And then, in this year when rap dominated the charts and provided the most innovative and creative music you could find on the radio, they decided not to televise any of the rap awards. Rap music was fully coming into its own creatively and commercially, but still being treated as if it wasn’t fit to sit in the company of the rest of the music community.