Decoded (21 page)

Authors: Jay-Z

Tags: #Rap & Hip Hop, #Rap musicians, #Rap musicians - United States, #Cultural Heritage, #Jay-Z, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Music, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Composers & Musicians, #Biography

YOU GOT IT, FUCK BUSH

Another Clinton was running for president in 2008, but, as much as I’d come to like the Clintons, I wasn’t supporting Hillary. Wasn’t even considering it. I’d done some campaign events in 2004 when Kerry was running for president, but in 2008, for the first time in my life, I was committed to a candidate for president in a big way.

A close friend of Barack Obama is a big fan of my music and reached out to someone in my camp to set up a meeting. This was still pretty early in the process, before the primaries had gotten started, and I hadn’t really engaged with the whole thing yet or given any money to anyone or anything. All I knew was that I was sick about what had happened with this country since 9/11, the wars and torture, the response to Hurricane Katrina, the arrogance and dishonesty of the Bush administration. I sat down with Barack at a one-on-one meeting set up by that mutual friend and we talked for hours. People always ask me what we talked about, and I wish I could remember some specific moment when it hit me that this guy was special. But it wasn’t like that. It was the fact that he sought me out and then asked question after question, about music, about where I’m from, about what people in my circle—not the circle of wealthy entertainers, but the wider circle that reaches out to my fans and all the way back to Marcy—were thinking and concerned about politically. He listened. It was extraordinary.

More than anything specific that he said, I was impressed by who he was. Supporters of Barack are sometimes criticized for getting behind him strictly because of his biography rather than his policies. I thought his policies were good, and I liked his approach to solving problems, but I’m not going to lie: Who he was was very important to me. He was my peer, or close to it, like a young uncle or an older brother. His defining experiences were in the nineties in the projects of Chicago, where he lived and worked as a community organizer before going to Harvard Law School. He’d seen me—or some version of me—in those Chicago streets, and we lived around a lot of the same kinds of things over those years, although obviously from very different angles. I could see he wasn’t going to be one of those guys who burned hip-hop in effigy to get a few votes. He even had the guts to tell the press that he had my music on his iPod.

And he was black. This was big. This was a chance to go from centuries of invisibility to the most visible position in the entire world. He could, through sheer symbolism, regardless of any of his actual policies, change the lives of millions of black kids who now saw something different to aspire to. That would happen on the day he was elected, regardless of anything else that happened in his term. No other candidate could promise so much.

Early on, there were a lot of influential black people who didn’t think he could win and withheld their support. I got into some serious arguments with people I respect over supporting Barack over Hillary. But I could see what Barack in the White House would mean to kids who were coming up the way I came up. And having met the man, I felt like Barack wasn’t going to lose. I ran into him again at a fund-raiser at L. A. Reid’s house and he pulled my coat: “Man, I’m going to be calling you again.”

I was touring at the time for the

American Gangster

album, and when I hit the lyric in “Blue Magic” where I say

fuck Bush,

I’d segue into “Minority Report,” my song about Hurricane Katrina from the

Kingdom Come

album. The jumbo screen behind me would go black and then up would come an image of Barack Obama. The crowd would always go wild. I would quickly make the point that Barack was not asking me to do this—and he hadn’t. I didn’t want him to get caught up in having to defend every one of my lyrics or actions. I’ve done some stuff even I have trouble explaining—I definitely didn’t want him to have to. I didn’t want my lyrics to end up in a question at a presidential debate. I knew enough about politics and the media to know that something that trivial could derail him.

I thought a lot about that. There were people like Reverend Jeremiah Wright who caused trouble for Barack because of things they’d said or done in the past but refused to lay low, even when it was clear they were hurting the cause. I was happy to play the back and not draw attention to myself. I didn’t need to be onstage or in every picture with him. I just wanted him to win.

But he did eventually call me and ask me to help. It was in the fall of the year and he told me he wanted to close it out like Jordan. So I did a bunch of free shows all over the country before the election to encourage young people to register to vote. I wasn’t surprised at the historically low rate of voting among young black people because I’d been there myself. But I had to make it clear to them: If you want shit to get better in your neighborhood, you have to be the one who puts the guy in office. If you vote for him, he owes you. That’s the game—it’s a hustle. But even aside from all that, I told people, this election is bigger than politics. As cliché as it might sound, it was about hope.

THIS MIGHT OFFEND MY POLITICAL CONNECTS

When I came to Washington for the inauguration—needless to say, the first inauguration of my life—I just wanted to soak it all in, every second of it. As soon as I walked into the lobby of the hotel where I was staying, the vibe was unlike anything I’d ever felt, people of all races and ages just thrilled to see each other. Beyoncé performed at the Lincoln Memorial the day before the inauguration and I decided to watch her from the crowd, so I could feel the energy of everyday people. It was unbelievable to see us—me, Beyoncé, Mary J. Blige, Puff, and other people I’ve known for so long, who represent people I’ve known my whole life—sharing in this rite of passage, one of America’s grandest displays of pageantry.

On the day of the inauguration, I came down in the elevator of the hotel with Ty-Ty. An older white woman in the elevator with us turned and admired Ty-Ty’s suit and gently straightened his tie. It wasn’t patronizing at all, it felt as comfortable as if we were family. We had seats for the ceremony, which was an unexpected honor, and from underneath my Russian mink hat (it was two degrees below zero) I watched Air Force II—the president’s helicopter, with George Bush in it—take off from the White House while a million people chanted nah-nah-nah-nah, hey, hey, hey, goodbye. And then the moment came when Barack faced the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and took the oath of office to become the forty-fourth President. That was when it hit me the hardest. We’d started so far outside of it—so far from power and visibility. But here we were.

The first show I played when I got to Washington, two days before the inauguration, was a little different from the official inaugural events I played, where I was keeping it presidential. It was at Club Love and I was dropping in on Jeezy’s set to do the remix version of “My President Is Black.” It was a real hip-hop show—stage crowded with niggas facing a hot, crowded club. It was the kind of show I’ve been doing since I was running with Kane. The spirit was familiar, too—the crowd was rocking to the music, arms in the air, getting the rush from being so close to the performers, so close to one another. But it was also different. There were people waving small American flags back at me. And onstage, we were all smiling. Grinning. We couldn’t control it. Jeezy had the funniest line of the night: “I know we’re thanking a lot of people … I want to thank two people: I want to thank the motherfucker overseas who threw two shoes at George Bush. And I want to thank the motherfuckers who helped him move his shit up out the White House.”

Those lines—in fact, the whole performance, which someone posted up on the Internet—would get twisted and cause a little stir among the right-wing media in the days that followed, which only validated my initial decision to lay low during the campaign. But it was over now and we’d won; fuck it—it was a celebration. We all had chills.

I remembered when I was still campaigning that fall, doing shows all over for voter registration. At one show in Virginia I was closing out my set and looked out at the audience, full of young black kids, laughing and hopeful. I tried to focus on the individual faces in that crowd, tried to find their eyes. That’s why I wanted Barack to win, so those kids could see themselves differently, could see their futures differently than I did when I was a kid in Brooklyn and my eyes were focused on a narrower set of possibilities. People think there’s no real distinction between the political parties, and in a lot of ways they’re right. America still has a tremendous amount of distance to cover before it’s a place that’s true to its own values, let alone to deeper human values. Since he’s been elected there have been a lot of legitimate criticisms of Obama.

But if he’d lost, it would’ve been an unbelievable tragedy—to feel so close to transformation and then to get sucked back in to the same old story and watch another generation grow up feeling like strangers in their own country, their culture maligned, their voices squashed. Instead, even with all the distance yet to go, for the fi rst time I felt like we were at least moving in the right direction, away from the shadows.

T

here are no white people in Marcy Projects. Bed-Stuy today has been somewhat gentrified, but the projects are like gentrification firewalls. When I was growing up there, it was strictly blacks and Puerto Ricans, maybe some Dominicans, rough Arabs who ran the twenty-four-hour bodegas, pockets of Hasidim who kept to themselves, and the Chinese dudes who stayed behind bullet-proof glass at the corner take-out joint. They supposedly sold Chinese food, but most people went there for the fried wings with duck sauce and the supersweet iced tea.

When I started working in Trenton we would see white people sometimes. There were definitely white crackheads; desperate white people weren’t any more immune to it than desperate black or Latino people. They’d leave their neighborhoods and come to ours to buy it. You could tell they were looking for crack because they’d slow down as they drove through the hood instead of speeding up. Sometimes they’d hang around to smoke it up. Make some new friends. But the truth is that in most neighborhoods, the local residents were the main customers. And the local residents tended to be black, maybe Latino.

That didn’t mean that white people were a mystery to me. If you’re an American, you’re surrounded on all sides by images of white people in popular culture. If anything, some black people can become poisoned by it and start hating themselves. A lot of us suffered from it—wanting to be light-skinned with curly hair. I never thought twice about trying to look white, but in little ways I was being poisoned, too, for example, in unconsciously accepting the common wisdom that light-skinned girls were the prettiest—

all wavy light-skinned girls is lovin me now.

It was sick.

CHECK OUT MY HAIR, THESE AIN’T CURLS THESE IS PEAS

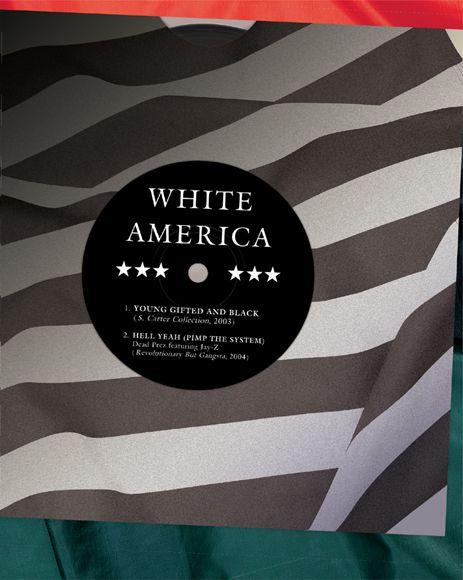

Hip-hop has always been a powerful force in changing the way people think about race, for better and worse. First it changed the way black people—especially black boys and men—thought about themselves. When I was a young teenager, the top black pop stars were Michael Jackson and Prince, two musical geniuses who fucked up a lot of black people in the head because of how deliberately they seemed to be running away from looking like black people. Their hair was silky straight, their skin was light, and in Michael’s case, getting lighter by the day. We didn’t know shit about vitiligo or whatever he had back then; we just saw the big, bouncy afro turn into a doobie and the black boy we loved turn white. But aside from Michael and Prince, who were so special that you could just chalk it up to their mad genius, we were getting hit with a stream of singers who weren’t exactly flying the flag of blackness. The Debarges and Apollonias and constant flow of Jheri curls. Male singers were taking the bass and texture out of their voices, trying to cross over and get some of that Lionel Richie money. It wasn’t their fault—and there was some good music that came out of that moment (shout-out to Al B. Sure!). But it wasn’t exactly affirming.