Delphi Complete Works of Ann Radcliffe (Illustrated) (228 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Ann Radcliffe (Illustrated) Online

Authors: Ann Radcliffe

On the twentieth of May, the day on which Ellena completed her eighteenth year, her nuptials with Vivaldi were solemnized in the church of the Santa Maria della Piéta, in the presence of the Marchese and of the Countess di Bruno. As Ellena advanced through the church, she recollected, when on a former occasion she had met Vivaldi at the altar, and, the scenes of San Sebastian rising to her memory, the happy character of those, which her present situation opposed to them, drew tears of tender joy and gratitude to her eyes. Then, irresolute, desolate, surrounded by strangers, and ensnared by enemies, she had believed she saw Vivaldi for the last time; now, supported by the presence of a beloved parent, and by the willing approbation of the person, who had hitherto so strenuously opposed her, they were met to part no more; and, as a recollection of the moment when she had been carried from the chapel glanced upon her mind, that moment when she had called upon him for succour, supplicated even to hear his voice once more, and when a blank silence, which, as she believed, was that of death, had succeeded; as the anguish of that moment was now remembered, Ellena became more than ever sensible of the happiness of the present.

Olivia, in thus relinquishing her daughter so soon after she had found her, suffered some pain, but she was consoled by the fair prospect of happiness, that opened to Ellena, and cheered, by considering, that, though she relinquished, she should not lose her, since the vicinity of Vivaldi’s residence to La Piéta, would permit a frequent intercourse with the convent.

As a testimony of singular esteem, Paulo was permitted to be present at the marriage of his master, when, as perched in a high gallery of the church, he looked down upon the ceremony, and witnessed the delight in Vivaldi’s countenance, the satisfaction in that of my “old Lord Marchese,” the pensive happiness in the Countess di Bruno’s, and the tender complacency of Ellena’s, which her veil, partly undrawn, allowed him to observe, he could scarcely refrain from expressing the joy he felt, and shouting aloud, “O! giorno felíce! O! giorno felíce!” [Note: O happy day! O happy day!]

“Ah! where shall I so sweet a dwelling find!

For all around, without, and all within,

Nothing save what delightful was and kind,

Of goodness favouring and a tender mind,

E’er rose to view.”

Thomson.

The fête which, some time after the nuptials, was given by the Marchese, in celebration of them, was held at a delightful villa, belonging to Vivaldi, a few miles distant from Naples, upon the border of the gulf, and on the opposite shore to that which had been the frequent abode of the Marchesa. The beauty of its situation and its interior elegance induced Vivaldi and Ellena to select it as their chief residence. It was, in truth, a scene of fairyland. The pleasure-grounds extended over a valley, which opened to the bay, and the house stood at the entrance of this valley, upon a gentle slope that margined the water, and commanded the whole extent of its luxuriant shores, from the lofty cape of Miseno to the bold mountains of the south, which, stretching across the distance, appeared to rise out of the sea, and divided the gulf of Naples from that of Salerno.

The marble porticoes and arcades of the villa were shadowed by groves of the beautiful magnolia flowering ash, cedrati, camellias, and majestic palms; and the cool and airy halls, opening on two opposite sides to a colonade, admitted beyond the rich soliage all the seas and shores of Naples, from the west; and to the east, views of the valley of the domain, withdrawing among winding hills wooded to their summits, except where cliffs of various-coloured granites, yellow, green, and purple, lifted their tall heads, and threw gay gleams of light amidst the umbrageous landscape.

The style of the gardens, where lawns and groves, and woods varied the undulating surface, was that of England, and of the present day, rather than of Italy; except “Where a long alley peeping on the main,” exhibited such gigantic loftiness of shade, and grandeur of perspective, as characterize the Italian taste.

On this jubilee, every avenue and grove, and pavilion was richly illuminated. The villa itself, where each airy hall and arcade was resplendent with lights, and lavishly decorated with flowers and the most beautiful shrubs, whose buds seemed to pour all Arabia’s perfumes upon the air, this villa resembled a fabric called up by enchantment, rather than a structure of human art.

The dresses of the higher rank of visitors were as splendid as the scenery, of which Ellena was, in every respect, the queen. But this entertainment was not given to persons of distinction only, for both Vivaldi and Ellena had wished that all the tenants of the domain should partake of it, and share the abundant happiness which themselves possessed; so that the grounds, which were extensive enough to accommodate each rank, were relinquished to a general gaiety. Paulo was, on this occasion, a sort of master of the revels; and, surrounded by a party of his own particular associates, danced once more, as he had so often wished, upon the moonlight shore of Naples.

As Vivaldi and Ellena were passing the spot, which Paulo had chosen for the scene of his festivity, they paused to observe his strange capers and extravagant gesticulation, as he mingled in the dance, while every now-and-then he shouted forth, though half breathless with the heartiness of the exercise, “O! giorno felíce! O! giorno felíce!”

On perceiving Vivaldi, and the smiles with which he and Ellena regarded him, he quitted his sports, and advancing, “Ah! my dear master,” said he, “do you remember the night, when we were travelling on the banks of the Celano, before that diabolical accident happened in the chapel of San Sebastian; don’t you remember how those people, who were tripping it away so joyously, by moonlight, reminded me of Naples and the many merry dances I had footed on the beach here?”

“I remember it well,” replied Vivaldi.

“Ah! Signor mio, you said at the time, that you hoped we should soon be here, and that then I should frisk it away with as glad a heart as the best of them. The first part of your hope, my dear master, you was out in, for, as it happened, we had to go through purgatory before we could reach paradise; but the second part is come at last; — for here I am, sure enough! dancing by moonlight, in my own dear bay of Naples, with my own dear master and mistress, in safety, and as happy almost as myself; and with that old mountain yonder, Vesuvius, which I, forsooth! thought I was never to see again, spouting up fire, just as it used to do before we got ourselves put into the Inquisition! O! who could have foreseen all this! O! giorno felíce! O! giorno felíce!”

“I rejoice in your happiness, my good Paulo,” said Vivaldi, “almost as much as in my own; though I do not entirely agree with you as to the comparative proportion of each.”

“Paulo!” said Ellena, “I am indebted to you beyond any ability to repay; for to your intrepid affection your master owes his present safety. I will not attempt to thank you for your attachment to him; my care of your welfare shall prove how well I know it; but I wish to give to all your friends this acknowledgment of your worth, and of my sense of it.”

Paulo bowed, and stammered, and writhed and blushed, and was unable to reply; till, at length, giving a sudden and lofty spring from the ground, the emotion which had nearly stifled him burst forth in words, and “O! giorno felíce! O! giorno felíce!” flew from his lips with the force of an electric shock. They communicated his enthusiasm to the whole company, the words passed like lightning from one individual to another, till Vivaldi and Ellena withdrew amidst a choral shout, and all the woods and strands of Naples re-echoed with— “O! giorno felíce! O! giorno felíce!”

“You see,” said Paulo, when they had departed, and he came to himself again, “you see how people get through their misfortunes, if they have but a heart to bear up against them, and do nothing that can lie on their conscience afterwards; and how suddenly one comes to be happy, just when one is beginning to think one never is to be happy again! Who would have guessed that my dear master and I, when we were clapped up in that diabolical place, the Inquisition, should ever come out again into this world! Who would have guessed when we were taken before those old devils of Inquisitors, sitting there all of a row in a place under ground, hung with black, and nothing but torches all around, and faces grinning at us, that looked as black as the gentry aforesaid; and when I was not so much as suffered to open my mouth, no! they would not let me open my mouth to my master! — who, I say, would have guessed we should ever be let loose again! who would have thought we should ever know what it is to be happy! Yet here we are all abroad once more! All at liberty! And may run, if we will, straight forward, from one end of the earth to the other, and back again without being stopped! May fly in the sea, or swim in the sky, or tumble over head and heels into the moon! For remember, my good friends, we have no lead in our consciences to keep us down!”

“You mean swim in the sea, and fly in the sky, I suppose,” observed a grave personage near him, “but as for tumbling over head and heels into the moon! I don’t know what you mean by that!”

“Pshaw!” replied Paulo, “who can stop, at such a time as this, to think about what he means! I wish that all those, who on this night are not merry enough to speak before they think, may ever after be grave enough to think before they speak! But you, none of you, no! not one of you! I warrant, ever saw the roof of a prison, when your master happened to be below in the dungeon, nor know what it is to be forced to run away, and leave him behind to die by himself. Poor souls! But no matter for that, you can be tolerably happy, perhaps, notwithstanding; but as for guessing how happy I am, or knowing any thing about the matter. — O! it’s quite beyond what you can understand. O! giorno felice! O! giorno felice!” repeated Paulo, as he bounded forward to mingle in the dance, and “O! giorno felice!” was again shouted in chorus by his joyful companions.

LE

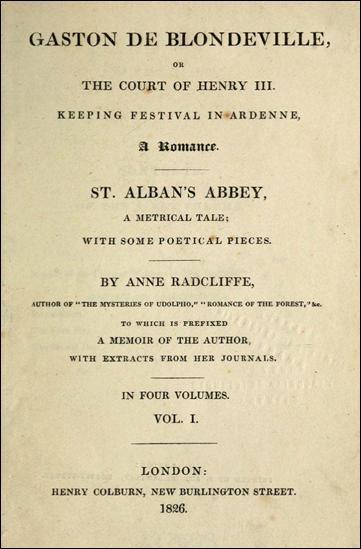

The Gaston de Blondeville

was written in the early ninteenth century, but published posthumously in 1826 by Henry Colburn, three years after Radcliffe’s death. The novel is set in the court of Henry III and centred on a trial held by Henry to determine claims against the title character Gaston. He is accused of having killed a merchant’s kinsman and despite Henry’s reservations about the allegations against Gaston, he has little choice but to order a trial. Radcliffe pays particular attention to the details of Henry III court; this attempted realism serves as a contrast to the fact that while she largely chose to explain the seemingly supernatural events in her novels with rational resolutions in

Gaston de Blondeville,

she features an actual ghost whose presence cannot be justified by reason. The ghost who wishes to expose the truth in the case is contrasted with the abbot who attempts to prevent what has happened from being revealed.

Religion once again features as a prominent aspect in Radcliffe’s fiction, with dubious connotations; the danger for both Gaston and his accuser Woodreeve increases as the trial progresses and the sinister machinations of the abbot come into focus. The reversal in Radcliffe’s approach to the explanation of the supernatural in this work compared to her other novels raises interesting questions about a variation of philosophy in this book. The rationalist approach in novels or literature during this period was often linked to rejection of the individualism and the emphasis on subjective desires that were frequently associated with the turbulence and violence of the French Revolution. The supernatural is the uncontrollable and irrational and therefore has the potential to threaten the social or political order.

The first edition was published posthumously in 1826.