Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) (1265 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) Online

Authors: SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

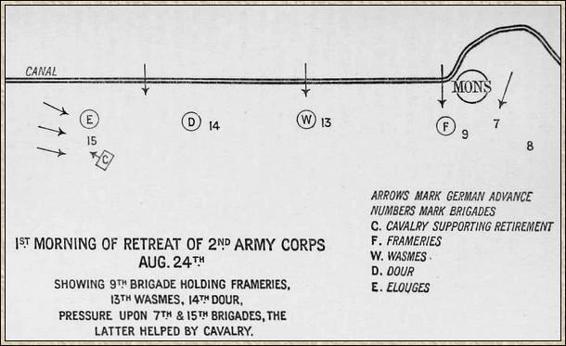

First Morning of Retreat of 2nd Army Corps, August 24, 1914

The first menacing advance in the morning of the 24th was directed against the flank of the British infantry who were streaming down the Elouges-Dour high-road. The situation was critical, and a portion of De Lisle’ s 2nd Cavalry Brigade was ordered to charge near Andregnies, the hostile infantry being at that time about a thousand yards distant, with several batteries in support. The attack of the cavalry was vigorously supported by L Battery of Horse Artillery. The charge was carried out by three squadrons of the 9th Lancers, Colonel Campbell at their head. The 4th Dragoon Guards under Colonel Mullens was in support. The cavalry rode forward amidst a heavy but not particularly deadly fire until they were within a few hundred yards of the enemy, when, being faced by a wire fence, they swung to the right and rallied under the cover of some slag-heaps and of a railway embankment. Their menace and rifle fire, or the fine work of Major Sclater-Booth’s battery, had the effect of holding up the German advance for some time, and though the cavalry were much scattered and disorganised they were able to reunite without any excessive loss, the total casualties being a little over two hundred. Some hours later the enemy’s pressure again became heavy upon Ferguson’s flank, and the 1st Cheshires and 1st Norfolks, of Gleichen’s 15th Brigade, which formed the infantry flank-guard, incurred heavy losses. It was in this defensive action that the 119th R.F.A., under Major Alexander, fought itself to a standstill with only three unwounded gunners by the guns. The battery had silenced one German unit and was engaged with three others. Only Major Alexander and Lieutenant Pollard with a few men were left. As the horses had been destroyed the pieces had to be man-handled out of action. Captain the Hon. F. Grenfell, of the 9th Lancers, bleeding from two wounds, with several officers, Sergeants Davids and Turner, and some fifty men of the regiment, saved these guns under a terrible fire, the German infantry being within close range.

During the whole long, weary day the batteries and horsemen were working hard to cover the retreat, while the surgeons exposed themselves with great fearlessness, lingering behind the retiring lines in order to give first aid to the men who had been hit by the incessant shell-fire. It was in this noble task — the noblest surely within the whole range of warfare — that Captain Malcolm Leckie, and other brave medical officers, met with a glorious end, upholding to the full the traditions of their famous corps.

It has been stated that the 1st Cheshires, in endeavouring to screen the west flank of the Second Corps from the German pursuit, were very badly punished. This regiment, together with the Norfolks, occupied a low ridge to the north-east side of the village of Elouges, which they endeavoured to hold against the onflowing tide of Germans. About three in the afternoon it was seen that there was danger of this small flank-guard being entirely cut off. As a matter of fact an order had actually been sent for a retreat, but had not reached them. Colonel Boger of the Cheshires sent several messengers, representing the growing danger, but no answer came back. Finally, in desperation. Colonel Boger went himself and found that the enemy held the position previously occupied by the rest of Gleichen’s Brigade, which had retired. The Cheshires had by this time endured dreadful losses, and were practically surrounded. A bayonet charge eased the pressure for a short time, but the enemy again closed in and the bulk of the survivors, isolated amidst a hostile army corps, were compelled to surrender. Some escaped in small groups and made their way through to their retreating comrades. When roll was next called, there remained 5 officers and 193 men out of 27 officers and 1007 of all ranks who had gone into action. It speaks volumes for the discipline of the regiment that this remnant, under Captain Shore, continued to act as a useful unit. These various episodes, including the severe losses of Gleichen’s 15th Brigade, the attack of the 2nd Cavalry Brigade, and the artillery action in which the 119th Battery was so severely handled, group themselves into a separate little action occurring the day after Mons and associated either with the villages of Elouges or of Dour. The Second German Corps continued to act upon the western side of the Second British Corps, whilst the rest of General von Kluck’s army followed it behind. With three corps close behind him, and one snapping at his flank. General Smith-Dorrien made his way southwards, his gunners and cavalry labouring hard to relieve the ever-increasing pressure, while his rear brigades were continually sprayed by the German shrapnel.

It is to be noted that Sir John French includes the Ninth German Corps in Von Kluck’s army in his first dispatch, and puts it in Von Bülow’s second army in his second dispatch. The French authorities are of opinion that Von Kluck’s army consisted of the Second, Third, Fourth, Seventh, and Fourth Reserve Corps, with two divisions of cavalry. If this be correct, then part of Von Bülow’s army was pursuing Haig, while the whole of Von Kluck’s was concentrated upon Smith-Dorrien. This would make the British performance even more remarkable than it has hitherto appeared, since it would mean that during the pursuit, and at the subsequent battle, ten German divisions were pressing upon three British ones.

It is not to be supposed that so huge a force was all moving abreast, or available simultaneously at any one point. None the less a General can use his advance corps very much more freely when he knows that every gap can be speedily filled.

A tiny reinforcement had joined the Army on the morning after the battle of Mons. This was the 19th Brigade under General Drummond, which consisted of the 1st Middlesex, 1st Scots Rifles, 2nd Welsh Fusiliers, and 2nd Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. This detached brigade acted, and continued to act during a large part of the war, as an independent unit. It detrained at Valenciennes on August 23, and two regiments, the Middlesex and the Cameronians, may be said to have taken part in the battle of Mons, since they formed up at the east of Condé, on the extreme left of the British position, and received, together with the Queen’s Bays, who were scouting in front of them, the first impact of the German flanking corps. They fell back with the Army upon the 24th and 25th, keeping the line Jenlain — Solesmes, finally reaching Le Cateau, where they eventually took up their position on the right rear of the British Army.

As the Army fell back, the border fortress of Maubeuge with its heavy guns offered a tempting haven of rest for the weary and overmatched troops, but not in vain had France lost her army in Metz. Sir John French would have no such protection, however violently the Germans might push him towards it. “The British Army Invested in Maubeuge” was not destined to furnish the headline of a Berlin special edition. The fortress was left to the eastward, and the tired troops snatched a few hours of rest near Bavai, still pursued by the guns and the searchlights of their persistent foemen. At an early hour of the 25th the columns were again on the march for the south, and for safety.

It may be remarked that in all this movement what made the operation most difficult and complicated was, that in the retirement the Army was not moving direct to the rear, but diagonally away to the west, thus making the west flank more difficult to cover as well as complicating the movements of transport. It was this oblique movement which caused the Third Division to change places with the Fifth, so that from now onwards it was to the west of the Army.

The greater part of the Fourth Division of the Third Army Corps, coming up from the lines of communication, brought upon this day a welcome reinforcement to the Army and did yeoman work in covering the retirement. The total composition of this division was as follows: —

THIRD ARMY CORPS — GENERAL PULTENEY. |

Division IV. — General Snow. |

10th Infantry Brigade — General Haldane. |

1st Warwicks. |

2nd Seaforths. |

1st Irish Fusiliers. |

2nd Dublin Fusiliers. |

11th Infantry Brigade — General Hunter-Weston. |

1st Somerset L. Infantry. |

1st East Lancashires. |

1st Hants. |

1st Rifle Brigade. |

12th Infantry Brigade — General Wilson. |

lst Royal Lancaster Regiment. |

2nd Lancs. Fusiliers. |

2nd Innis. Fusiliers. |

2nd Essex. |

Artillery — General Milne. |

XIV. Brig. R.F.A. 39, 68, 88. |

XXIX. Brig. R.F.A. 125, 126, 127. |

XXXII. Brig. R.F.A. 27, 134, 135. |

XXXVII. Brig. R.F.A. (How.) 31, 35, 55. |

Heavy R.G.A. 31 Battery. |

R.E. 7, 9 Field Cos. |

These troops, which had been quartered in the Ligny and Montigny area, received urgent orders at one in the morning of the 25th that they should advance northwards. They marched that night to Briastre, where they covered the retreat of the Army, the Third Division passing through their lines. The Fourth Division then retired south again, having great difficulty in getting along, as the roads were choked with transport and artillery, and fringed with exhausted men. The 12th Brigade (Wilson’s) was acting as rearguard, and began to experience pressure from the pursuers, the Essex men being shelled out of the village of Bethencourt, which they held until it was nearly surrounded by the German cavalry. The line followed by the division was Briastre-Viesly-Bethencourt-Caudry-Ligny and Haucourt, the latter village marking the general position which they were to take up on the left of the Army at the line of Le Cateau. Such reinforcements were mere handfuls when compared with the pursuing hosts, but their advent heartened up the British troops and relieved them of some of the pressure. It has been remarked by officers of the Fourth Division that they and their men were considerably taken aback by the worn appearance of the weary regiments from Mons which passed through their ranks. Their confidence was revived, however, by the undisturbed demeanour of the General Headquarters Staff, who came through them in the late afternoon of the 25th. “General French himself struck me as being extremely composed, and the staff officers looked very cheerful.” These are the imponderabilia which count for much in a campaign.

Tuesday, August 25, was a day of scattered rearguard actions. The weary Army had rested upon the evening of the 24th upon the general line Maubeuge -Bavai-Wargnies. Orders were issued for the retirement to continue next day to a position already partly prepared, in front of the centre of which stood the town of Le Cateau. All rearguards were to be clear of the above-mentioned line by 5:30 A.M. The general conception was that the inner flanks of the two corps should be directed upon Le Cateau.

The intention of the Commander-in-Chief was that the Army should fight in that position next day, the First Corps occupying the right and the Second Corps the left of the position. The night of the 25th found the Second Corps in the position named, whilst their comrades were still at Landrecies, eight miles to the north-east, with a cavalry brigade endeavouring to bridge the gap between. It is very certain, in the case of so ardent a leader as Haig, that it was no fault upon his part which kept him from Smith-Dorrien’s side upon the day of battle. It can only be said that the inevitable delays upon the road experienced by the First Corps, including the rear-guard actions which it fought, prevented the ensuing battle from being one in which the British Army as a whole might have stemmed the rush of Von Kluck’s invading host.

Whilst the whole Army had been falling back upon Solesmes, the position which had been selected for a stand, it was hoped that substantial French reinforcements were coming up from the south. The roads were much blocked during the 25th, for two divisions of French territorials were retiring along them, as well as the British Army. As a consequence progress was slow, and the German pressure from the rear became ever more severe. Allenby’s cavalry and horse-guns covered the retreat, continually turning round and holding off the pursuers. Finally, near Solesmes, on the evening of the 25th, the cavalry were at last driven in, and the Germans came up against McCracken’s 7th Brigade, who held them most skilfully until nightfall with the assistance of the 42nd Brigade R.F.A. and the 30th Howitzer Brigade. Most of the fighting fell upon the 1st Wiltshires and 2nd South Lancashires, both of which had substantial losses. The Germans could make no further progress, and time was given for the roads to clear and for the artillery to get away. The 7th Brigade then followed, marching, so far as possible, across country The Battle and taking up its position, which it did not reach until after midnight, in the village of Caudry, on the line of the Le Cateau — Courtrai road. As it faced north once more it found Snow’s Fourth Division upon its left, while on its immediate right were the 8th and the 9th Brigades, with the Fifth Division on the farther side of them. One unit of the 7th Brigade, the 2nd Irish Rifles, together with the 41st R.F.A., swerved off in the darkness and confusion and went away with the cavalry. The rest were in the battle line. Here we may leave them in position while we return to trace the fortunes of the First Army Corps.

Sir Douglas Haig’s corps, after the feint of August

The guns having been drawn in, the corps retired by roads parallel to the Second Corps, and were able to reach the line Bavai — Maubeuge by about 7 P.M. upon that evening, being on the immediate eastern flank of Smith-Dorrien’s men. It is a striking example of the historical continuity of the British Army that as they marched that day many of the regiments, such as the Guards and the 1st King’s Liverpool, passed over the graves of their predecessors who had died under the same colours at Malplaquet in 1709, two hundred and six years before.

On August 25 General Haig continued his retreat. During the day he fell back to the west of Maubeuge by Feignies to Vavesnes and Landrecies. The considerable forest of Mormal intervened between the two sections of the British Army. On the forenoon of this day the vanguard of the German infantry, using motor transport, overtook Davies’ 6th Brigade, which was acting as rearguard to the corps. They pushed in to within five hundred yards, but were driven back by rifle-fire. Other German forces were coming rapidly up and enveloping the wings of the British rearguard, but the brigade, through swift and skilful handling, disengaged itself from what was rapidly becoming a dangerous situation. The weather was exceedingly hot during the day, and with their heavy packs the men were much exhausted, many of them being barely able to stagger. In the evening, footsore and weary, they reached the line of Landrecies, Maroilles, and Pont-sur-Sambre. The 4th Brigade of Guards, consisting of Grenadiers, Coldstream, and Irish, under General Scott-Kerr, occupied the town of Landrecies. During the day they had seen little of the enemy, and they had no reason to believe that the forest, which extended up to the outskirts of the town, was full of German infantry pressing eagerly to cut them off. The possession of vast numbers of motor lorries for infantry transport introduces a new element into strategy, especially the strategy of a pursuit, which was one of those disagreeable first experiences of up-to-date warfare which the British Army had to undergo. It ensures that the weary retreating rearguard shall ever have a perfectly fresh pursuing vanguard at its heels.

The Guards at Landrecies were put into the empty cavalry barracks for a much-needed rest, but they had hardly settled down before there was an alarm that the Germans were coming into the town. It was just after dusk that a column of infantry debouched from the shadow of the trees and advanced briskly towards the town. A company of the 3rd Coldstream under Captain Monck gave the alarm, and the whole regiment stood to arms, while the rest of the brigade, who could not operate in so confined a space, defended the other entrances of the town. The van of the approaching Germans shouted out that they were French, and seemed to have actually got near enough to attack the officer of the picket and seize a machine-gun before the Guardsmen began to fire. There is a single approach to the village, and no means of turning it, so that the attack was forced to come directly down the road.

Possibly the Germans had the impression that they were dealing with demoralised fugitives, but if so they got a rude awakening. The advance party, who were endeavouring to drag away the machine-gun, were all shot down, and their comrades who stormed up to the houses were met with a steady and murderous fire which drove them back into the shadows of the wood. A gun was brought up by them, and fired at a range of five hundred yards with shrapnel, but the Coldstream, reinforced by a second company, lay low or flattened themselves into the doorways for protection, while the 9th British Battery replied from a position behind the town. Presently, believing that the way had been cleared for them, there was a fresh surge of dark masses out of the wood, and they poured into the throat of the street. The Guards had brought out two machine-guns, and their fire, together with a succession of volleys from the rifles, decimated the stormers. Some of them got near enough to throw hand-bombs among the British, but none effected a lodgment among the buildings.

From time to time there were fresh advances during the night, designed apparently rather to tire out the troops than to gain the village. Once fire was set to the house at the end of the street, but the flames were extinguished by a party led by Corporal Wyatt, of the 3rd Coldstream. The Irish Guards after midnight relieved the Coldstream of their vigil, and in the early morning the tired but victorious brigade went forward unmolested upon their way. They had lost 170 of their number, nearly all from the two Coldstream companies. Lord Hawarden and the Hon. Windsor Clive of the Coldstream and Lieut. Vereker of the Grenadiers were killed, four other officers were wounded. The Germans in their close attacking formation had suffered very much more heavily. Their enterprise was a daring one, for they had pushed far forward to get command of the Landrecies Bridge, but their audacity became foolhardy when faced by steady, unshaken infantry. History has shown many times before that a retreating British Army still retains a sting in its tail.

At the same time as the Guards’ Brigade was attacked at Landrecies there was an advance from the forest against Maroilles, which is four miles to the eastward. A troop of the 15th Hussars guarding a bridge over the Sambre near that point was driven in by the enemy, and two attempts on the part of the 1st Berkshires, of Davies’ 6th Brigade, to retake it were repulsed, owing to the fact that the only approach was by a narrow causeway with marshland on either side, where it was not possible for infantry to deploy. The 1st Rifles were ordered to support the Berkshires, but darkness had fallen and nothing could be done. The casualties in this skirmish amounted to 124 killed, wounded, or missing. The Landrecies and Maroilles wounded were left behind with some of the medical staff. At this period of the war the British had not yet understood the qualities of the enemy, and several times made the mistake of trusting surgeons and orderlies to their mercy, with the result that they were inhumanly treated, both by the authorities at the front and by the populace in Germany, whither they were conveyed as starving prisoners of war. Five of them, Captains Edmunds and Hamilton, Lieut. Danks (all of the Army Medical Corps), with Dr. Austin and Dr. Elliott, who were exchanged in January 1915, deposed that they were left absolutely without food for long periods. It is only fair to state that at a later date, with a few scandalous exceptions, such as that of Wittenberg, the German treatment of prisoners, though often harsh, was no longer barbarous. For the first six months, however, it was brutal in the extreme, and frequently accompanied by torture as well as neglect. A Spanish prisoner, incarcerated by mistake, has given very clear neutral evidence of the abominable punishments of the prison camps. His account reads more like the doings of Iroquois than of a Christian nation.

A Small mishap — small on the scale of such a war, though serious enough in itself — befell a unit of the First Army Corps on the morning after the Landrecies engagement. The portion of the German army who pursued General Haig had up to now been able to effect little, and that little at considerable cost to themselves. Early on August 26, however, a brisk action was fought near Pont-sur-Sambre, in which the 2nd Connaughts, of Haking’s Fifth Brigade, lost six officers, including Colonel Abercrombie, who was taken prisoner, and 280 men. The regiment was cut off by a rapidly advancing enemy in a country which was so thickly enclosed that there was great difficulty in keeping touch between the various companies or in conveying their danger to the rest of the brigade. By steadiness and judgment the battalion was extricated from a most difficult position, but it was at the heavy cost already quoted. In this case again the use by the enemy of great numbers of motor lorries in their pursuit accounts for the suddenness and severity of the attacks which now and afterwards fell upon the British rearguards.

Dawn broke upon August