Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) (656 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) Online

Authors: SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

“Some of us may. I don’t expect to see the padre alive to-morrow, nor Miss Adams either. They are not made for this sort of thing, either of them. Then, again, we must not forget that these people have a trick of murdering their prisoners when they think that there is a chance of a rescue. See here, Belmont, in case you get back and I don’t, there’s a matter of a mortgage that I want you to set right for me.” They rode on with their shoulders inclined to each other, deep in the details of business.

The friendly negro who had talked of himself as Tippy Tilly had managed to slip a piece of cloth soaked in water into the hand of Mr. Stephens, and Miss Adams had moistened her lips with it. Even the few drops had given her renewed strength, and, now that the first crushing shock was over, her wiry, elastic, Yankee nature began to reassert itself.

“These people don’t look as if they would harm us, Mr. Stephens,” said she. “I guess they have a working religion of their own, such as it is, and that what’s wrong to us is wrong to them.”

Stephens shook his head in silence. He had seen the death of the donkey-boys, and she had not.

“Maybe we are sent to guide them into a better path,” said the old lady. “Maybe we are specially singled out for a good work among them.”

If it were not for her niece her energetic and enterprising temperament was capable of glorying in the chance of evangelising Khartoum, and turning Omdurman into a little well-drained, broad-avenued replica of a New England town.

“Do you know what I am thinking of all the time?” said Sadie. “You remember that temple that we saw, — when was it? Why, it was this morning.”

They gave an exclamation of surprise, all three of them. Yes, it had been this morning; and it seemed away and away in some dim past experience of their lives, so vast was the change, so new and so overpowering the thoughts which had come between them. They rode in silence, full of this strange expansion of time, until at last Stephens reminded Sadie that she had left her remark unfinished.

“Oh, yes; it was the wall picture on that temple that I was thinking of. Do you remember the poor string of prisoners who are being dragged along to the feet of the great king, — how dejected they looked among the warriors who led them? Who could, — who

could

have thought that within three hours the same fate should be our own? And Mr. Headingly —— ,” she turned her face away and began to cry.

“Don’t take on, Sadie,” said her aunt; “remember what the minister said just now, that we are all right there in the hollow of God’s hand. Where do you think we are going, Mr. Stephens?”

The red edge of his Baedeker still projected from the lawyer’s pocket, for it had not been worth their captor’s while to take it. He glanced down at it.

“If they will only leave me this, I will look up a few references when we halt. I have a general idea of the country, for I drew a small map of it the other day. The river runs from south to north, so we must be travelling almost due west. I suppose they feared pursuit if they kept too near the Nile bank. There is a caravan route, I remember, which runs parallel to the river, about seventy miles inland. If we continue in this direction for a day we ought to come to it. There is a line of wells through which it passes. It comes out at Assiout, if I remember right, upon the Egyptian side. On the other side, it leads away into the Dervish country, — so, perhaps — —”

His words were interrupted by a high, eager voice which broke suddenly into a torrent of jostling words, words without meaning, pouring strenuously out in angry assertions and foolish repetitions. The pink had deepened to scarlet upon Mr. Stuart’s cheeks, his eyes were vacant but brilliant, and he gabbled, gabbled, gabbled as he rode. Kindly mother Nature! she will not let her children be mishandled too far. “This is too much,” she says; “this wounded leg, these crusted lips, this anxious, weary mind. Come away for a time, until your body becomes more habitable.” And so she coaxes the mind away into the Nirvana of delirium, while the little cell-workers tinker and toil within to get things better for its home-coming. When you see the veil of cruelty which nature wears, try and peer through it, and you will sometimes catch a glimpse of a very homely, kindly face behind.

The Arab guards looked askance at this sudden outbreak of the clergyman, for it verged upon lunacy, and lunacy is to them a fearsome and supernatural thing. One of them rode forward and spoke with the Emir. When he returned he said something to his comrades, one of whom closed in upon each side of the minister’s camel, so as to prevent him from falling. The friendly negro sidled his beast up to the Colonel, and whispered to him.

“We are going to halt presently, Belmont,” said Cochrane.

“Thank God! They may give us some water. We can’t go on like this.”

“I told Tippy Tilly that, if he could help us, we would turn him into a Bimbashi when we got him back into Egypt. I think he’s willing enough if he only had the power. By Jove, Belmont, do look back at the river.”

Their route, which had lain through sand-strewn khors with jagged, black edges, — places up which one would hardly think it possible that a camel could climb, — opened out now on to a hard, rolling plain, covered thickly with rounded pebbles, dipping and rising to the violet hills upon the horizon. So regular were the long, brown pebble-strewn curves, that they looked like the dark rollers of some monstrous ground-swell. Here and there a little straggling sage-green tuft of camel-grass sprouted up between the stones. Brown plains and violet hills, — nothing else in front of them! Behind lay the black jagged rocks through which they had passed with orange slopes of sand, and then far away a thin line of green to mark the course of the river. How cool and beautiful that green looked in the stark, abominable wilderness! On one side they could see the high rock, — the accursed rock which had tempted them to their ruin. On the other the river curved, and the sun gleamed upon the water. Oh, that liquid gleam, and the insurgent animal cravings, the brutal primitive longings, which for the instant took the soul out of all of them! They had lost families, countries, liberty, everything, but it was only of water, water, water, that they could think. Mr. Stuart, in his delirium, began roaring for oranges, and it was insufferable for them to have to listen to him. Only the rough, sturdy Irishman rose superior to that bodily craving. That gleam of river must be somewhere near Haifa, and his wife might be upon the very water at which he looked. He pulled his hat over his eyes, and rode in gloomy silence, biting at his strong, iron-grey moustache.

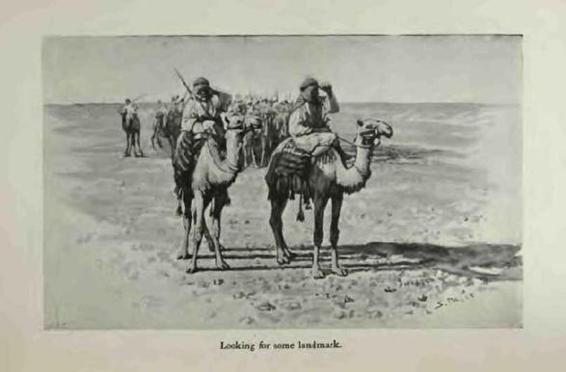

Slowly the sun sank towards the west, and their shadows began to trail along the path where their hearts would go. It was cooler, and a desert breeze had sprung up, whispering over the rolling, stone-strewed plain. The Emir at their head had called his lieutenant to his side, and the pair had peered about, their eyes shaded by their hands, looking for some landmark. Then, with a satisfied grunt, the chiefs camel had seemed to break short off at its knees, and then at its hocks, going down in three curious, broken-jointed jerks until its stomach was stretched upon the ground. As each succeeding camel reached the spot it lay down also, until they were all stretched in one long line. The riders sprang off, and laid out the chopped tibbin upon cloths in front of them, for no well-bred camel will eat from the ground. In their gentle eyes, their quiet, leisurely way of eating, and their condescending, mincing manner, there was something both feminine and genteel, as though a party of prim old maids had foregathered in the heart of the Libyan desert.

There was no interference with the prisoners, either male or female, for how could they escape in the centre of that huge plain? The Emir came towards them once, and stood combing out his blue-black beard with his fingers, and looking thoughtfully at them out of his dark, sinister eyes. Miss Adams saw with a shudder that it was always upon Sadie that his gaze was fixed. Then, seeing their distress, he gave an order, and a negro brought a water-skin, from which he gave each of them about half a tumblerful. It was hot and muddy and tasted of leather, but, oh, how delightful it was to their parched palates! The Emir said a few abrupt words to the dragoman and left.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” Mansoor began, with something of his old consequential manner; but a glare from the Colonel’s eyes struck the words from his lips, and he broke away into a long, whimpering excuse for his conduct.

“How could I do anything otherwise,” he wailed, “with the very knife at my throat?”

“You will have the very rope round your throat if we all see Egypt again,” growled Cochrane, savagely. “In the meantime—”

“That’s all right, Colonel,” said Belmont. “But for our own sakes we ought to know what the chief has said.”

“For my part I’ll have nothing to do with the blackguard.”

“I think that that is going too far. We are bound to hear what he has to say.”

Cochrane shrugged his shoulders. Privations had made him irritable, and he had to bite his lip to keep down a bitter answer. He walked slowly away, with his straight-legged military stride.

“What did he say then?” asked Belmont, looking at the dragoman with an eye which was as stern as the Colonel’s.

“He seems to be in a somewhat better manner than before. He said that if he had more water you should have it, but that he is himself short in supply. He said that tomorrow we shall come to the wells of Selimah, and everybody shall have plenty — and the camels too.”

“Did he say how long we stopped here?”

“Very little rest, he said, and then forwards! Oh, Mr. Belmont — —”

“Hold your tongue!” snapped the Irishman, and began once more to count times and distances. If it all worked out as he expected, if his wife had insisted upon the indolent reis giving an instant alarm at Haifa, then the pursuers should be already upon their track. The Camel Corps or the Egyptian Horse would travel by moonlight better and faster than in the daytime. He knew that it was the custom at Haifa to keep at least a squadron of them all ready to start at any instant. He had dined at the mess, and the officers had told him how quickly they could take the field. They had shown him the water-tanks and the food beside each beast, and he had admired the completeness of the arrangements, with little thought as to what it might mean to him in the future. It would be at least an hour before they would all get started again from their present halting-place. That would be a clear hour gained. Perhaps by next morning ——

And then, suddenly, his thoughts were terribly interrupted. The Colonel, raving like a madman, appeared upon the crest of the nearest slope, with an Arab hanging on to each of his wrists. His face was purple with rage and excitement, and he tugged and bent and writhed in his furious efforts to get free. “You cursed murderers!” he shrieked, and then, seeing the others in front of him, “Belmont,” he cried, “they’ve killed Cecil Brown.”

What had happened was this. In his conflict with his own ill-humour, Cochrane had strolled over this nearest crest, and had found a group of camels in the hollow beyond, with a little knot of angry, loud-voiced men beside them. Brown was the centre of the group, pale, heavy-eyed, with his upturned, spiky moustache and listless manner. They had searched his pockets before, but now they were determined to tear off all his clothes in the hope of finding something which he had secreted. A hideous negro, with silver bangles in his ears, grinned and jabbered in the young diplomatist’s impassive face. There seemed to the Colonel to be something heroic and almost inhuman in that white calm, and those abstracted eyes. His coat was already open, and the negro’s great black paw flew up to his neck and tore his shirt down to the waist. And at the sound of that r-r-rip, and at the abhorrent touch of those coarse fingers, this man about town, this finished product of the nineteenth century, dropped his life-traditions and became a savage facing a savage.

His face flushed, his lips curled back, he chattered, his teeth like an ape, and his eyes — those indolent eyes which had always twinkled so placidly — were gorged and frantic. He threw himself upon the negro, and struck him again and again, feebly but viciously, in his broad, black face. He hit like a girl, round arm, with an open palm. The man winced away for an instant, appalled by this sudden blaze of passion. Then with an impatient, snarling cry he slid a knife from his long loose sleeve and struck upwards under the whirling arm. Brown sat down at the blow and began to cough — to cough as a man coughs who has choked at dinner, furiously, ceaselessly, spasm after spasm. Then the angry red cheeks turned to a mottled pallor, there were liquid sounds in his throat, and, clapping his hand to his mouth, he rolled over on to his side.