Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) (657 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) Online

Authors: SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

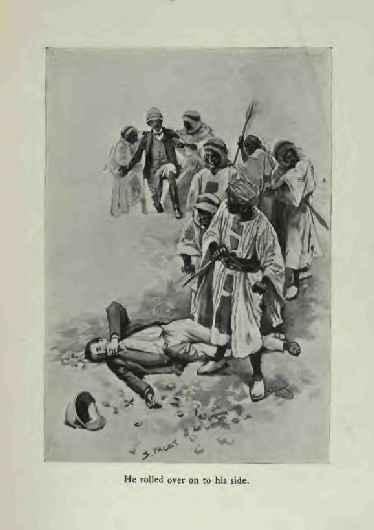

The negro, with a brutal grunt of contempt, slid his knife up his sleeve once more, while the Colonel, frantic with impotent anger, was seized by the bystanders, and dragged, raving with fury, back to his forlorn party. His hands were lashed with a camel-halter, and he lay at last, in bitter silence, beside the delirious Nonconformist.

So Headingly was gone, and Cecil Brown was gone, and their haggard eyes were turned from one pale face to another, to know which they should lose next of that frieze of light-hearted riders who had stood out so clearly against the blue morning sky, when viewed from the deck-chairs of the

Korosko

. Two gone out of ten, and a third out of his mind. The pleasure trip was drawing to its climax.

Fardet, the Frenchman, was sitting alone with his chin resting upon his hands, and his elbows upon his knees, staring miserably out over the desert, when Belmont saw him start suddenly and prick up his head like a dog who hears a strange step. Then, with clenched fingers, he bent his face forward and stared fixedly towards the black eastern hills through which they had passed. Belmont followed his gaze, and, yes — yes — there was something moving there! He saw the twinkle of metal, and the sudden gleam and flutter of some white garment.

A Dervish vedette upon the flank turned his camel twice round as a danger signal, and discharged his rifle in the air. The echo of the crack had hardly died away before they were all in their saddles, Arabs and negroes. Another instant, and the camels were on their feet and moving slowly towards the point of alarm. Several armed men surrounded the prisoners, slipping cartridges into their Remingtons as a hint to them to remain still.

“By Heaven, they are men on camels!” cried Cochrane, his troubles all forgotten as he strained his eyes to catch sight of these new-comers. “I do believe that it is our own people.” In the confusion he had tugged his hands free from the halter which bound them.

“They’ve been smarter than I gave them credit for,” said Belmont, his eyes shining from under his thick brows. “They are here a long two hours before we could have reasonably expected them.

Hurrah, Monsieur Fardet,

ça va bien, n’est ce pas?

”

“Hurrah, hurrah!

merveilleusement bien!

Vivent les Anglais! Vivent les Anglais!

” yelled the excited Frenchman, as the head of a column of camelry began to wind out from among the rocks.

“See here, Belmont,” cried the Colonel. “These fellows will want to shoot us if they see it is all up. I know their ways, and we must be ready for it. Will you be ready to jump on the fellow with the blind eye, and I’ll take the big nigger, if I can get my arms around him. Stephens, you must do what you can. You, Fardet,

comprenez vous? Il est nécessaire

to plug these Johnnies before they can hurt us. You, dragoman, tell those two Soudanese soldiers that they must be ready — but, but — —” his words died into a murmur and he swallowed once or twice. “These are Arabs,” said he, and it sounded like another voice.

Of all the bitter day, it was the very bitterest moment. Happy Mr. Stuart lay upon the pebbles with his back against the ribs of his camel, and chuckled consumedly at some joke which those busy little cell-workers had come across in their repairs.

His fat face was wreathed and creased with merriment. But the others, how sick, how heart-sick, were they all! The women cried. The men turned away in that silence which is beyond tears. Monsieur Fardet fell upon his face, and shook with dry sobbings.

The Arabs were firing their rifles as a welcome to their friends, and the others as they trotted their camels across the open returned the salutes and waved their rifles and lances in the air. They were a smaller band than the first one, — not more than thirty, — but dressed in the same red head-gear and patched jibbehs. One of them carried a small white banner with a scarlet text scrawled across it. But there was something there which drew the eyes and the thoughts of the tourists away from everything else. The same fear gripped at each of their hearts, and the same impulse kept each of them silent. They stared at a swaying white figure half seen amidst the ranks of the desert warriors.

“What’s that they have in the middle of them?” cried Stephens at last. “Look, Miss Adams! Surely it is a woman!”

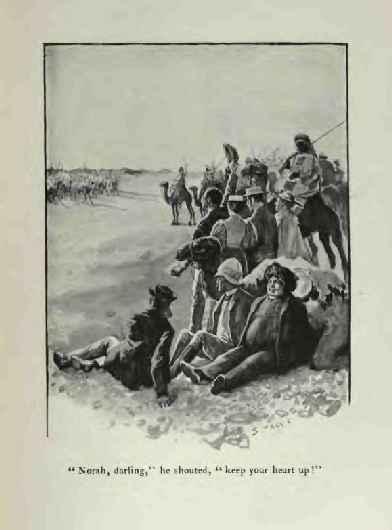

There was something there upon a camel, but it was difficult to catch a glimpse of it. And then suddenly, as the two bodies met, the riders opened out, and they saw it plainly. “It’s a white woman!” “The steamer has been taken!” Belmont gave a cry that sounded high above everything.

“Norah, darling,” he shouted, “keep your heart up! I’m here, and it is all well!”

So the

Korosko

had been taken, and the chances of rescue upon which they had reckoned — all those elaborate calculations of hours and distances — were as unsubstantial as the mirage which shimmered upon the horizon. There would be no alarm at Haifa until it was found that the steamer did not return in the evening. Even now, when the Nile was only a thin green band upon the farthest horizon, the pursuit had probably not begun. In a hundred miles or even less they would be in the Dervish country. How small, then, was the chance that the Egyptian forces could overtake them. They all sank into a silent, sulky despair, with the exception of Belmont, who was held back by the guards as he strove to go to his wife’s assistance.

The two bodies of camel-men had united, and the Arabs, in their grave, dignified fashion, were exchanging salutations and experiences, while the negroes grinned, chattered, and shouted, with the careless good-humour which even the Koran has not been able to alter. The leader of the new-comers was a greybeard, a worn, ascetic, high-nosed old man, abrupt and fierce in his manner, and soldierly in his bearing. The dragoman groaned when he saw him, and flapped his hands miserably with the air of a man who sees trouble accumulating upon trouble.

“It is the Emir Abderrahman,” said he. “I fear now that we shall never come to Khartoum alive.”

The name meant nothing to the others, but Colonel Cochrane had heard of him as a monster of cruelty and fanaticism, a red-hot Moslem of the old fighting, preaching dispensation, who never hesitated to carry the fierce doctrines of the Koran to their final conclusions. He and the Emir Wad Ibrahim conferred gravely together, their camels side by side, and their red turbans inclined inwards, so that the black beard mingled with the white one. Then they both turned and stared long and fixedly at the poor, head-hanging huddle of prisoners. The younger man pointed and explained, while his senior listened with a sternly impassive face.

“Who’s that nice-looking old gentleman in the white beard?” asked Miss Adams, who had been the first to rally from the bitter disappointment.

“That is their leader now,” Cochrane answered.

“You don’t say that he takes command over that other one?”

“Yes, lady,” said the dragoman; “he is now the head of all.”

“Well, that’s good for us. He puts me in mind of Elder Mathews, who was at the Presbyterian Church in minister Scott’s time. Anyhow, I had rather be in his power than in the hands of that black-haired one with the flint eyes. Sadie, dear, you feel better now its cooler, don’t you?”

“Yes, Auntie; don’t you fret about me. How are you yourself?”

“Well, I’m stronger in faith than I was.

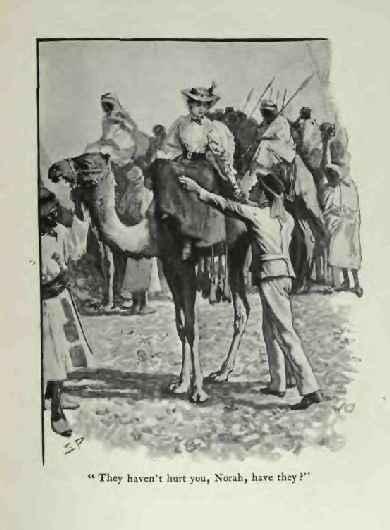

“They haven’t hurt you, Norah, have they?”

“I set you a poor example, Sadie, for I was clean crazed at first at the suddenness of it all, and at thinking of what your mother, who trusted you to me, would think about it. My land, there’ll be some headlines in the

Boston Herald

over this! I guess somebody will have to suffer for it.”

“Poor Mr. Stuart!” cried Sadie, as the monotonous, droning voice of the delirious man came again to their ears. “Come, Auntie, and see if we cannot do something to relieve him.”

“I’m uneasy about Mrs. Shlesinger and the child,” said Colonel Cochrane. “I can see your wife, Belmont, but I can see no one else.”

“They are bringing her over,” cried he. “Thank God! We shall hear all about it. They haven’t hurt you, Norah, have they?” He ran forward to grasp and kiss the hand which his wife held down to him as he helped her from the camel.

The kind, grey eyes and calm, sweet face of the Irishwoman brought comfort and hope to the whole party. She was a devout Roman Catholic, and it is a creed which forms an excellent prop in hours of danger. To her, to the Anglican Colonel, to the Nonconformist minister, to the Presbyterian American, even to the two Pagan black riflemen, religion in its various forms was fulfilling the same beneficent office, — whispering always that the worst which the world can do is a small thing, and that, however harsh the ways of Providence may seem, it is, on the whole, the wisest and best thing for us that we should go cheerfully whither the Great Hand guides us. They had not a dogma in common, these fellows in misfortune, but they held the intimate, deep-lying spirit, the calm, essential fatalism which is the world-old framework of religion, with fresh crops of dogmas growing like ephemeral lichens upon its granite surface.

“You poor things,” she said. “I can see that you have had a much worse time than I have. No, really, John, dear, I am quite well, — not even very thirsty, for our party filled their waterskins at the Nile, and they let me have as much as I wanted. But I don’t see Mr. Headingly and Mr. Brown. And poor Mr. Stuart, — what a state he has been reduced to!”

“Headingly and Brown are out of their troubles,” her husband answered. “You don’t know how often I have thanked God to-day, Norah, that you were not with us. And here you are, after all.”

“Where should I be but by my husband’s side? I had much,

much

rather be here than safe at Haifa.”

“Has any news gone to the town?” asked the Colonel.

“One boat escaped. Mrs. Shlesinger and her child and maid were in it. I was downstairs in my cabin when the Arabs rushed on to the vessel. Those on deck had time to escape, for the boat was alongside. I don’t know whether any of them were hit. The Arabs fired at them for some time.”

“Did they?” cried Belmont, exultantly, his responsive Irish nature catching the sunshine in an instant. “Then, be Jove, we’ll do them yet, for the garrison must have heard the firing. What d’ye think, Cochrane? They must be full cry upon our scent this four hours. Any minute we might see the white puggaree of a British officer coming over that rise.”

But disappointment had left the Colonel cold and sceptical.

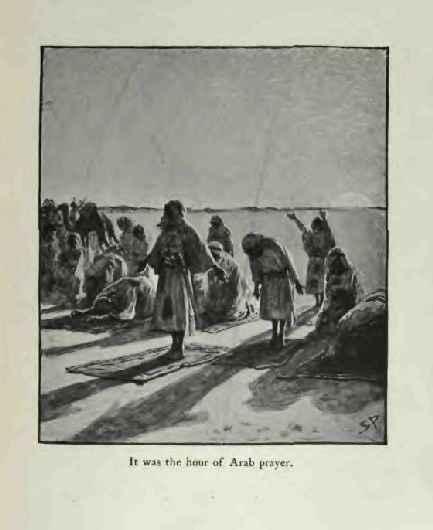

“They need not come at all unless they come strong,” said he. “These fellows are picked men with good leaders, and on their own ground they will take a lot of beating.” Suddenly he paused and looked at the Arabs. “By George!” said he, “that’s a sight worth seeing!”

The great red sun was down with half its disc slipped behind the violet bank upon the horizon. It was the hour of Arab prayer. An older and more learned civilisation would have turned to that magnificent thing upon the skyline and adored

that

. But these wild children of the desert were nobler in essentials than the polished Persian. To them the ideal was higher than the material, and it was with their backs to the sun and their faces to the central shrine of their religion that they prayed. And how they prayed, these fanatical Moslems! Wrapt, absorbed, with yearning eyes and shining faces, rising, stooping, grovelling with their foreheads upon their praying carpets. Who could doubt, as he watched their strenuous, heart-whole devotion, that here was a great living power in the world, reactionary but tremendous, countless millions all thinking as one from Cape Juby to the confines of China? Let a common wave pass over them, let a great soldier or organiser arise among them to use the grand material at his hand, and who shall say that this may not be the besom with which Providence may sweep the rotten, decadent, impossible, half-hearted south of Europe, as it did a thousand years ago, until it makes room for a sounder stock?

And now as they rose to their feet the bugle rang out, and the prisoners understood that, having travelled all day, they were fated to travel all night also. Belmont groaned, for he had reckoned upon the pursuers catching them up before they left this camp. But the others had already got into the way of accepting the inevitable. A flat Arab loaf had been given to each of them — what effort of the

chef

of the post-boat had ever tasted like that dry brown bread? — and then, luxury of luxuries, they had a second ration of a glass of water, for the fresh-filled bags of the new-comers had provided an ample supply. If the body would but follow the lead of the soul as readily as the soul does that of the body, what a heaven the earth might be! Now, with their base material wants satisfied for the instant, their spirits began to sing within them, and they mounted their camels with some sense of the romance of their position. Mr. Stuart remained babbling upon the ground, and the Arabs made no effort to lift him into his saddle. His large, white, upturned face glimmered through the gathering darkness.

“Hi, dragoman, tell them that they are forgetting Mr. Stuart,” cried the Colonel.

“No use, sir,” said Mansoor. “They say that he is too fat, and that they will not take him any farther. He will die, they say, and why should they trouble about him?”

“Not take him!” cried Cochrane. “Why, the man will perish of hunger and thirst. Where’s the Emir? Hi!” he shouted, as the black-bearded Arab passed, with a tone like that in which he used to summon a dilatory donkey-boy. The chief did not deign to answer him, but said something to one of the guards, who dashed the butt of his Remington into the Colonel’s ribs.

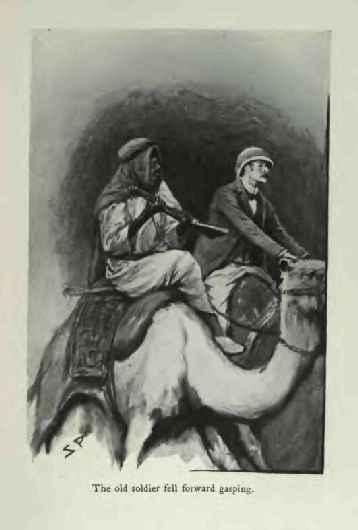

The old soldier fell forward gasping, and was carried on half senseless, clutching at the pommel of his saddle. The women began to cry, and the men with muttered curses and clenched hands writhed in that hell of impotent passion, where brutal injustice and ill-usage have to go without check or even remonstrance. Belmont gripped at his hip-pocket for his little revolver, and then remembered that he had already given it to Miss Adams. If his hot hand had clutched it, it would have meant the death of the Emir and the massacre of the party.

And now as they rode onwards they saw one of the most singular of the phenomena of the Egyptian desert in front of them, though the ill treatment of their companion had left them in no humour for appreciating its beauty. When the sun had sunk, the horizon had remained of a slaty-violet hue. But now this began to lighten and to brighten until a curious false dawn developed, and it seemed as if a vacillating sun was coming back along the path which it had just abandoned. A rosy pink hung over the west, with beautifully delicate sea-green tints along the upper edge of it. Slowly these faded into slate again, and the night had come. It was but twenty-four hours since they had sat in their canvas chairs discussing politics by starlight on the saloon deck of the

Korosko

; only twelve since they had breakfasted there and had started spruce and fresh upon their last pleasure trip. What a world of fresh impressions had come upon them since then! How rudely they had been jostled out of their take-it-for-granted complacency! The same shimmering silver stars as they had looked upon last night, the same thin crescent of moon — but they, what a chasm lay between that old pampered life and this!