Delphi Works of Ford Madox Ford (Illustrated) (309 page)

Read Delphi Works of Ford Madox Ford (Illustrated) Online

Authors: Ford Madox Ford

This was the longest speech that she had ever made, and her words failed her. In the failing light only her white forehead was visible, and then she went through the doorway. Anne Jeal remained upon her knees, scratching the wood of the floor with her finger-nail for a long time afterwards. At last she raised her arm on high, and whispered —

“Great God! Where is Thy justice, that one should have all and one of us nothing at all?” She was silent, and then she cried out, “Great God! What was her love to mine that Thou shouldst give her such a strength and render me so weak?”

By then it had grown quite dark.

UPON the

Half Moon

that had swung a little way up the river with the tide — a matter of six or seven miles or so — Hudson waited with a great impatience after the sun got low. They had dropped the anchor and lay about where the red and rocky wall was in that part at its highest. At one time they had heard a gun-shot from the thick woods on the left-hand side of them when they faced seawards; but they heard no more sounds till towards three of the afternoon, when there were two gun-shots almost abreast of them — but a little far inland. Then there was no more sound — and a great anxiety fell upon Hudson.

He had a little boat out and rowed up and down the rocky shore of the left Hand; the trees came almost down to the water’s edge; it was a very hot day, and many sea-birds and great eagles sat on the stones of the shore. But the sun went down, and the blood-red light turned the red rocks to a colour so bright that it hurt the eyes to see them. The

Half Moon

lay still on the silent river; fishes sprang up here and there; the night fell and the moon gave a little light. Far up in the hills they thought they saw a glow as of a faint fire, but they could not be certain that it was not a last glimmer of the sunset over the black tree-tops.

At last Hudson swore he heard a faint moaning almost abreast of them, that he saw a faint blackness on the shore or in the water, moving about up and down. He had out a boat and steered through the quiet; and then they knew that it was a faint voice that cried out.

Outreweltius stood there up to his waist in the water. He was quite calm, and still carried his stand gun, but he said that Edward Colman was dead and old Jan either dead or taken. He said that the Indians had ringed them round all that afternoon among the trees as if they were afraid. Once or twice they had fired arrows in showers, but these had always rebounded from their breastplates and helmets, so that he deemed the savages thought them godlike and invulnerable. But at last one arrow had struck the palm of old Jan where it was unprotected, and he had given a great cry of pain. They were in a sort of glade then, with the sunlight upon them — and immediately old Jan cried out the Indians, as if they saw these were no more than men, had burst out twenty or thirty yards above them, bedizened and hideous in the sunlight, all copper-skinned, bedaubed with ochre, waving stone hatchets and leaping in the air, shooting arrows in a cloud as they came, it seemed many hundreds of them among the rocks. An arrow had struck Edward Colman in the soft part of the neck, glancing down off his helm between helmet and cuirass. Both old Jan and himself had fired with their stand-guns, but when he stepped back to reload he had fallen down into a sort of pit that was quite covered with briars and bushes. He had known no more of the fight, for he had lain quite still, only he heard cries and voices and the feet of men going round among the bushes. And he had lain there still, the pit at its top being quite closed out from the sky by the verdure and thorns. But at nightfall he had crept out of the pit and so down to the river, where they had come to lake him.

Next morning, whilst they still debated on the

Half Moon,

there came down to the water a great many copper-coloured men with feathers on their backs and painted with ochre. Amongst them they had a white man quite naked. They stayed their howling until the

Half Moon

sent a boat near the shore — and it was to be seen that the white man among them was old Jan with his beard falling upon his naked chest.

One of the Indians, a man of huge stature, made to them in the boat a long speech. He pointed to the sea, to eastward, and to the heavens above; he raised one finger and then six; he affected to draw his bow and shook his head; he made as women do when they cast ashes on their heads and bewail the dead. The warriors around him leaned up in their bows and were silent. From time to time old Jan screamed and jabbered and then the chief paused and looked at him, afterwards resuming his sonorous words. Finally he paused for a long time too, and leaning on his own bow seemed to await speech from the boat. He was a man near seven feet high, and his coronal of feathers made him appear to have a great majesty. Suddenly he uttered one single word, and he and all his companions had vanished into the road as if they had sunk into the ground.

Old Jan remained alone on the shore, naked and gibbering, and when they drove the boat to take him aboard he ran away over the stones of the shore, crying out unintelligible words. But at last he fell down, and they bound him with the rope and took him aboard.

Henry Hudson was like a man mad with grief for a time; he cried out upon the Dutchmen that it was because of their firing on the canoes that the Indians had slain his innocent mate and friend, and he said that the Indians with their clemency were better Christians than they all. But they could not understand one word in ten of what he said, and at last, signing them to up-anchor, he went down into his cabin to be lonely with his grief. So they sailed away up that broad stream.

THE END

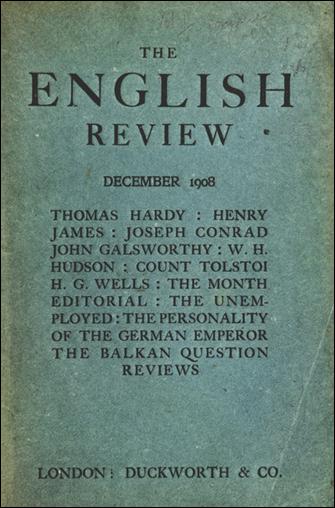

In December 1908 Ford established

The English Review

, a literary periodical, with the first issue containing original work by Thomas Hardy, Henry James, Joseph Conrad, John Galsworthy, W.H. Hudson and H. G. Wells, with even a short story by Leo Tolstoy.

This high standard of literature was maintained in later issues, with Ford introducing the early work of Ezra Pound and D. H. Lawrence, amongst other aspiring and future modern masters.

In 1910 Ford published his novel

A Call

as a serial in the magazine.

Written at a time when the editor had published works by the leading literary figures of the day, it is easy to understand Ford’s eagerness to contribute his best work to the journal. Now, some critics argue that

A Call

is Ford’s greatest achievement to be published before his masterpiece

The Good Soldier.

The novel tells the story of Robert Grimshaw, a thirty-five year old Londoner, who is a typical Fordian figure of indecisiveness, meddling in the affairs of other characters.

Grimshaw is caught between his passion for two entirely different women.

Firstly there is the headstrong and passionate Katya, who wishes to dominate him completely whilst living together unmarried; secondly, there is the supine and passive Pauline, who adores Grimshaw tenderly, with unquestioning devotion.

A recurring theme of the novel is the dance known as ‘lancers’, a type of quadrille set to a fixed number of steps, which the characters enact in their actions up until the tragic end. Ford’s novel depicts the two fundamentally different aspects of love with artistic deftness, conveying the sense of a world fraught with passion and agonised denial – a characteristic already familiar in Ford’s works, but one that had yet to be portrayed so successfully.

The first issue of Ford’s publishing sensation ‘The English Review’

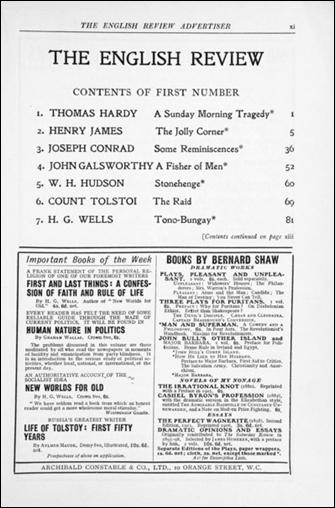

The first page of the table of contents

CONTENTS