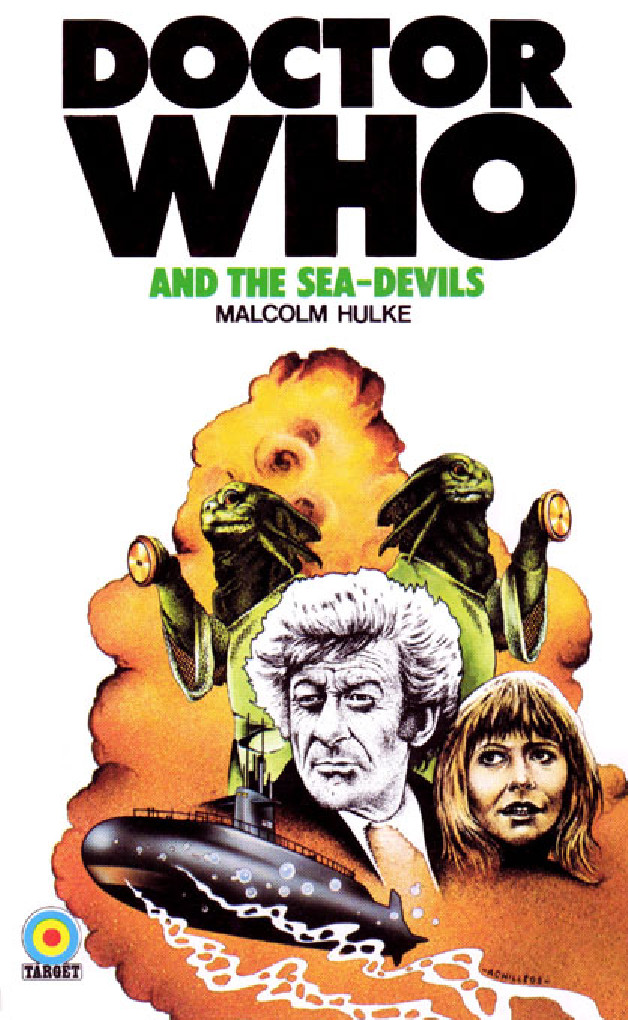

Doctor Who: The Sea-Devils

AND THE

SEA-DEVILS

By MALCOLM HULKE

Based on the BBC television serial The Sea-Devils by Malcolm Hulke by arrangement with the British Broadcasting Corporation

1 ‘Abandon Ship!’

‘

Abandon ship! Abandon ship!

’

Second Officer Mason could hear the Captain’s voice coming from every loudspeaker on the ship as he worked his way along the upper deck. A huge sea was sending waves and spray over the decks: a Force Nine gale was blowing in from the south west, and now, almost unbelievably, it seemed the bottom had been ripped out of the ship. She was lurching badly to port, poised to vanish any moment beneath the huge waves. Mason pulled his way along a handrail until he came across some of the engine-room crew; they were desperately trying to lower one of the lifeboats.

‘Where’s Jock?!’ he called, yelling above the noise of the crashing waves. ‘And where’s the Jamaican?’

One of the engine-room men, nicknamed The Scouse, yelled back to Mason: ‘They’re dead! They’re both dead!’

Mason could not believe the men were dead. Only two hours ago, before he turned in for the night, he had been drinking cocoa with the Jamaican. The Jamaican, who really came from Trinidad and had never been to Jamaica in his life, had shown Mason a letter from his mother who lived in a town called St. James. ‘It’s carnival next month,’ said the Jamaican, ‘and she wants her best-looking son back home for Carnival—and that’s me!’ He had saved his air fare, and was booked on a flight from London Airport three days after the s.s.

Pevensey Castle

got into the Port of London, where she was bound. And now the Jamaican, and Jock, and goodness knew how many others, were all dead.

Mason struggled over to help the men from the engine-room lower the lifeboat. He had the greatest respect for engineers when they were in the engine-rooms, but he was not impressed with their upperdeck seamanship.

‘Steady there!’ he shouted, and took one of the winches himself. There were four men on the winches, and five men huddled in the boat. Under Mason’s guidance, the lifeboat was evenly lowered into the boiling sea.

‘

Abandon ship! Abandon ship!

’

The Captain’s voice again boomed out over the loudspeakers. Mason wondered whether the Captain intended to stay on his bridge giving out the order to abandon ship until there was no ship left to abandon. Traditionally a ship’s captain was supposed to be the last man on board if the ship was sinking, and some captains had been known to stay on the bridge beyond the margin of safety, and to die as a result. Mason hoped his captain would be sensible, and get into one of the lifeboats while there was still a chance.

The Scouse called into Mason’s ear: ‘She’s hit water!’

Mason looked down. The lifeboat was now riding on the sea, and the men down there were letting loose the davit ropes. He cupped his hands to his mouth and called down to them, ‘Get rowing—pull away! Pull away!’

But the men in the lifeboat did not need to be told. They all knew that when a big ship finally sinks, she will drag with her any small craft standing close by. They had their oars out, and they were rowing frantically. Then the smoke started to rise from their little boat. Mason stared in horror as thick black smoke burst from the woodwork by the men’s feet. Within moments the whole bottom of the inside of the lifeboat started to glow with the redness of fire that was coming up from the sea beneath the little boat!

The Scouse and the other engine-room men looked down at the stricken lifeboat. ‘It must have had petrol in its bottom,’ said the Scouse, his voice choking and barely audible against the gale, ‘and one of them’s dropped a lighted cigarette.’

Mason did not believe this, but said nothing. With the spray and the waves it would be impossible for any man to smoke a cigarette, or even for loose petrol to ignite. He sensed that what he was witnessing had no explanation that would ever be known to himself or to the men around him. The whole lifeboat had by now burst into flames, that defied all the seawater, and the five occupants had tumbled overboard.

‘Lifebelts!’ Mason shouted. ‘We can throw them lifebelts!’

Two of the engine-room men struggled along the lurching deck to get lifebelts. But they were not going to save the five men now struggling desperately in the water. As Mason and the Scouse watched, one of the bobbing bodies abruptly disappeared under the water, as though grabbed and pulled down. There was a brief underwater struggle, evidenced by bubbles and foam—then nothing.

‘Sharks!’ said the Scouse. ‘Killer sharks!’

Mason did not bother to argue. Killer sharks do not use underwater blow-lamps, don’t set fire to lifeboats. Killer sharks do not lurk in the waters off the coast of southern England. Mason grabbed the handrail and pulled himself up the steeply sloping deck towards the radio-room. As he left the Scouse, who stood staring at the men in the water, another man was savagely pulled under. By now Mason knew that they were all doomed... the ship would be gone in another minute, and every man who got into a lifeboat, or into the sea, was going to meet the same fate as the men he’d already seen go down.

The stricken vessel was almost on its side as Mason yanked open the door of the radio-room. Sparks, as they had all called him, was still at his post, calling urgently into a microphone:

‘

May Day, May Day! This is s.s. Pevensey Castle. We are abandoning ship!

’

‘Give me the microphone,’ ordered Mason. He reached out and took the microphone from Sparks.

‘

We are being attacked!

’ Mason screamed into the microphone. ‘

The bottom of our ship has been ripped out. Men are being pulled dow

n into the sea—

’

Mason stopped abruptly and stared at the Sea-Devil now standing in the doorway. It had the general shape of a man, yet its body was covered in green scales, and the face was that of a snout-nosed reptile.

‘Sea-lizards,’ said Sparks, seeking some explanation, however unscientific, for the creature standing before them.

The Sea-Devil turned its head and looked at Sparks, as though it had understood what he said. Then it raised its right paw, and Mason saw that it carried a highly sophisticated weapon—a sort of gun.

‘You’re intelligent,’ said Mason, ‘you understand. You’re not an animal at all!’ For a brief moment Mason had hopes that this thing, whatever it was, might be there to save them. It was, literally, the hope of a drowning man clutching for a straw in the water.

The Sea-Devil killed Sparks first, then Mason. No trace of them, or of the s.s.

Pevensey Castle

, would ever be found — except for one empty lifeboat that the Sea-Devils somehow failed to destroy completely.

Jo Grant definitely felt sea-sick. She had travelled through Time and Space with the Doctor in the TARDIS, but that was very much more comfortable than sitting, as she was now, in a small open fishing-boat with a noisy outboard motor. It wasn’t only the motion of the boat that made her feel ill: the fast-revving little motor was blowing off petrol fumes that a slight breeze blew straight into her face, and the water they were crossing had on it slicks of oil, occasional dead fish, empty bobbing plastic milk bottles, and some rather unpleasant-looking items that may have come direct from the main sewer.

The Doctor leaned towards Jo, shouting above the noise of the little engine. ‘Feeling all right?’

She nodded. ‘Fine,’ she said, without much enthusiasm. ‘When do we get there?’

‘As the porcupine said to the turtle,’ shouted the Doctor, ‘“When we get there”’. It sounded like a quotation from

Alice in Wonderland

, but Jo suspected the Doctor had just made it up. The Doctor turned to the boatman, a Mr. Robbins, and shouted at him: ‘Is it in sight, yet?’

The boatman nodded and pointed with a rather dirty finger. Jo looked towards the island to which they were heading, and now, as they rounded a headland, she could see a very large isolated house, something on the lines of a French château. ‘That’s where they got him,’ Robbins shouted. ‘It’s a disgrace, if you ask me.’

‘Not large enough?’ said the Doctor, trying to make a joke.

Robbins shook his head, taking the Doctor seriously. ‘If you ask me,’ he shouted, ‘if you really wants my opinion, as an ordinary man in the street, as a taxpayer that’s got to pay for all the guards and everything, I’ll tell you what they should have done.’ He drew a finger swiftly across his throat. ‘

That’s

what he deserved.’

Mr. Robbins, the boatman, was expressing a widely-held view as to what should have happened to the Master. It was not without reason. Through Doctor Who, Jo had known about the Master for some time. She had been with the Doctor, a thousand years into the future and on another planet, when the Master had tried to take control of the Doomsday Weapon in his quest for universal power. More recently the Master had brought himself directly to the attention of the public on Earth by his efforts to conspire with dæmons, using psionic science to release the powers of a monster called Azal.

*

It was this that had brought about his downfall. He had been finally trapped and arrested by Brigadier Lethbridge Stewart of the United Nations Intelligence Taskforce—UNIT—and put on trial at a special Court of Justice. Although the horror of capital punishment had long been established in Great Britain, many people had wanted to see the Master put to death. To the amazement of the Brigadier, however, the Doctor had made a personal plea to the Court for the Master’s life to be spared. Naturally the Doctor could not explain in public that both he and the Master were not really of this planet, and that at one time both had been Time Lords. No Court would have believed him! But in his plea the Doctor talked of the Master’s better qualities—his intelligence, and his occasional wit and good humour. Jo well-remembered the Doctor’s final words to the Judges: ‘My Lords, I beg you to spare the prisoner’s life, for by so doing you will acknowledge that there is always the possibility of redemption, and that is an important principle for us all. If we do not believe that anyone, even the worst criminal, can be saved from wickedness, then in what can we ever believe?’ After six hours of private discussion the Judges had decided to sentence the Master to life-long imprisonment. They did not realise that, in the case of a Time Lord, ‘life-long’ might mean a thousand years!

The British authorities had then been faced with a big problem: where was the Master to be imprisoned? Brigadier Lethbridge Stewart had then written a long letter directly to the Prime Minister, trying to explain that the Master was no ordinary prisoner. It was no good putting him in even the most top security prison. For one thing, he had the ability to hypnotise people. Generally, hypnotists can only use their powers over other people who want to be hypnotised; but the Master had only to speak to a potential victim in a certain way, and—unless they were very strong minded—he had them under his spell. The Doctor had also written a long letter to the Prime Minister. He had endorsed the Brigadier’s warning, but then added a point of his own. When criminals, even murderers, are sentenced to ‘life’ imprisonment they usually only serve about ten years; this is because when a judge says ‘life’ he really means that the length of time in prison can be decided by the Prison Department, depending on a prisoner’s good behaviour and chances of leading a good life if he is eventually released. But in the case of the Master, the Judges had specifically said ‘life-long’, which meant until the Master died of old age. The Doctor, therefore, had asked the Prime Minister to use his compassion and to grant to the Master very considerate treatment. ‘The Master’s loss of freedom,’ the Doctor had written, ‘will be punishment enough. I suggest that in your wisdom you create a special prison for him, where he will be able to live in reasonable comfort, and where he will have the opportunity to pursue his intellectual interests.’

The Prime Minister had taken the advice of both the Brigadier and the Doctor. At enormous expense, a huge château on an off-shore island had been bought by the Government and turned into a top security prison—for just one prisoner. What the Prime Minister had done may have been right and proper, but it had cost taxpayers like Mr. Robbins the boatman a great deal of money. So, many people like Mr. Robbins—millions of them—had good reason to feel that the Master should have been put to death, and as quickly as possible.

The little open fishing-boat had now entered a small harbour. The water was calm here, but twice as polluted with muck. Jo kept her eyes on the quayside, to avoid seeing what floated all around her.

‘How long are you going to be?’ queried Robbins, as he stopped the engine, letting the boat glide towards the quay.

‘Maybe an hour,’ said the Doctor. ‘Can you wait for us?’

Robbins nodded. ‘You’ll find me round there somewhere,’ and he pointed to a café on the quayside. ‘Mind, I’ll have to charge extra for waiting.’ He produced a long pole with a hook on the end, used it to secure a hold on a metal ring set in the cobblestones on the quayside. ‘Can you make us up?’