Dog Diaries 07 - Stubby (4 page)

“Listen, Stubby. It’s seven-thirty, and that tune you just heard the bugler playing was ‘Reveille,’ ” Conroy said. “It’s French for

time to wake up and get moving.

When the bugle blows at ten o’clock, it’s ‘Taps.’

Taps

means

lights out, and hit the sack.

In the army, we all do everything together at the same time every day. Right now, it’s time to wash up. Uncle Sam wants us clean as a whistle. That’s what the latrine is for.”

In the latrine there was a long row of shining sinks. The soldiers splashed water on their faces and cleaned their teeth with little brushes. Some of the men lathered up their cheeks with soap and ran a flat metal stick over them. Others stood underneath the spray of a shower and scrubbed themselves, singing at the top of their lungs.

I sure hoped Conroy wasn’t expecting

me

to get clean. One time, a street sweeper accidentally splashed me with water. It took me forever to get dirty again. Until I did, I had no idea who I was. A dog’s smell is who a dog

is.

Conroy was busy lathering up his face. “You’re lucky you don’t have to shave every morning.”

Didn’t I know it!

When all this cleaning business was over, we headed to a sweet-smelling shack Conroy called the mess hall. He grabbed a tin plate and stood on the chow line. I sniffed it out as we went. We passed a big pot of scrambled eggs, another filled with white mushy stuff, and a griddle loaded up with fried spuds. Maybe it was because I was born in a nest of spud sacks, but I’ve always been fond of potatoes. I’d eat them any old way, but I especially liked them when they were fried up in bacon

grease, which these fine crispy babies were.

The soldiers didn’t seem happy about the food.

“I’ve had

garbage

that tastes better than this swill,” the guy in front of Conroy said.

Obviously, this guy had never enjoyed the privilege of eating

real

garbage.

“Belly robber!” another groused to the man who was serving it up.

“Don’t look at me,” said the man. “I just sling it. I don’t cook it.”

The men grumbled and made faces. But they choked down the food anyway. Conroy sat on a bench at a long table, elbow to elbow with other soldiers. I squeezed beneath the table, between his feet. Every bite of food came to me served up on Conroy’s buttery fingers. I don’t know what kind of garbage these soldiers had been eating, but the stuff tasted swell to me.

Afterward, I went with Conroy to a field. It was surrounded by rows of wooden seats.

“This is called the Yale Bowl, Stubby,” Conroy said. “Before the war, they played football here. Now we use it to train for combat.”

Conroy and the other soldiers carried rifles. I’d seen rifles before, propped on soldiers’ shoulders as they marched down Main Street on parade. But these rifles had sharp knives stuck on the ends of them.

“This is a bayonet,” Conroy told me. “Dangerous to little doggies.”

I gave all the bayonets plenty of space.

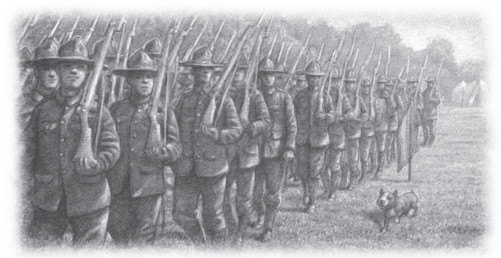

I sat on the sidelines and watched as the men marched across the field in long, straight lines.

Sarge caught sight of me and glared. “What are you looking at, soldier? Look lively, and fall in!”

Confused, I stared back at Sarge. Conroy called,

“Here, boy! Stay with me, okay?”

I scrambled until I caught up with him. Then I ran alongside him as he marched. When Conroy halted, I halted. When Conroy turned, I turned. When Conroy lifted his rifle, I stood back and watched out for the pointy tip of the bayonet.

Sarge walked up and down the lines. As he passed, each man raised an arm, bent at the elbow, and hit the side of his head.

Would somebody tell me why these soldiers keep hitting themselves in the head?

You wouldn’t catch a dog doing that.

Then the men stood in two long lines, facing each other. Their feet were wide apart, and they aimed their bayonets at the throats of the men standing across from them. I growled at the one with the bayonet pointing at my soldier boy.

“It’s okay, Stubby. It’s just a game,” Conroy told me.

I stopped growling, but I didn’t like this game.

Sarge strolled along, correcting the way the soldiers held their rifles. He said, “The bayonet can be a good friend to only

one

man—you or your enemy. Your life depends upon your learning how to handle it. Your hold should be firm, but relaxed. Your stance should be balanced and solid. You don’t want your opponent to push you off your feet. Then your goose is cooked.”

Sarge went along and tried to push the soldiers over. Some of them stumbled and fell. Conroy got

a good, hard shove, but his feet stayed planted.

Conroy’s goose is safe,

I thought.

After bayonet practice, the men marched in line with their rifles over their shoulders.

“About FACE!” Sarge barked.

The men all turned to face Sarge.

“Present ARMS!” he shouted.

The men held their rifles out in front of them. Sarge walked along and looked at the guns. Then he stood back and barked some more. The men lowered the rifle butts to the ground. Then they lifted them from the ground to their shoulders. Next, they picked the rifles up and went down on one knee. They peered down the barrels of the rifles.

“Prepare to fire!” Sarge yelled.

The men put their fingers on the triggers.

“FIRE!”

S

TOWAWAY

!

I was sure I was a goner. The sound knocked me clean off my feet. I squeezed my eyes shut and never expected to see daylight again. All around me, rifles EXPLODED. It was the loudest sound I had ever heard, louder than the Town Center Park on the Fourth of July when they set off those pesky fireworks.

When the noise died down, I blinked and opened my eyes.

I was still in one piece. The air was thick with smoke. My ears were ringing like the bell on the knife sharpener’s cart. My fur—what little I had—was standing on end. And I was shaking like a whippet on a block of ice.

Conroy touched me, and I nearly jumped out of my skin.

“Easy, boy,” he said. He patted me, smoothing my fur and speaking in a soft, gentle voice. Finally, I managed to calm down and regain my bull terrier cool.

“These are combat drills, Stubby. We’re practicing to fight in a war,” he explained. “The bullets are blanks, so no one will get hurt, but they still make plenty of noise. We’ve got to get used to the racket so we don’t lose our heads in battle. If you want to be in the army, you’ll have to put up with it.”

I wasn’t sure about the army, but I sure wanted to be with Conroy. And after a few days of drills, I did get used to it. In fact, it got so that when the soldiers fired their rifles, I just panted and grinned. Bring it on, boys!

One afternoon, the guys lined up and charged at a row of soldiers. They shouted and stabbed at the men with their bayonets—and straw flew out of their bodies!

What is this craziness?

I ran around and barked my fool head off. Then Conroy showed me that the soldiers were just uniforms stuffed with straw. That was a relief! Still, I had to admit I liked rifle practice better than this squirrely business with the bayonets. Something about all that stabbing and yelling and flying straw just set me off.

One day after lunch, when we were back in the Yale Bowl, Conroy knelt before me on the sidelines

and took my head in his hands. I stared at him. Today, he was wearing a helmet.

“Stay,” he said.

I watched as Conroy and the others got down on their bellies. Hugging their rifles and slithering along on their elbows like big snakes, they made their way through the grass. Slowly but surely, they were all crawling away from me.

Have I said that I really hated being left behind? Sad to say, I hated it so much that I disobeyed Conroy. I got down on my belly and crawled until I had caught up with him. It was a little hard on the elbows, but kind of fun. Next thing I knew, something came whistling through the air and exploded nearby. The earth beneath me shook. The soldiers covered their heads with their arms as bits and pieces of rock and earth rained down on us. I covered my head, too, for all the good it did. This

was no fun after all. I guess I should have stayed put like Conroy had told me.

But Conroy wasn’t mad. He was proud. “That’s my brave boy, Stubby,” he whispered to me from beneath his arm.

Easy for him to say. He had that nice hard helmet on his head.

Helmet or not, I hadn’t lost my head. But it ached a bit from all the noise and excitement. I was

glad to see that no one had gotten hurt, although a lot of the men had a spooked look about them. Maybe they were thinking the same thing I’d been thinking:

If this was just practice, what would the real thing be like?

And so it went, day after day: “Reveille,” latrine, mess hall, and drills, drills, drills. By the time the bugle boy blew “Taps” each night, I’d be curled up in my doggie bed, all tuckered out. It didn’t take me long to learn the routines and exercises so well that I could do them in my sleep. In fact, I woke myself up one night, covering my head with my paws as a shell exploded in my dream.

One evening, after chow and just before “Taps,” Conroy said to me, “I’ve got something for you, boy.”

More food?

I thought. Call me an optimist.

It was almost better than food. It was a dog collar.

A nice sturdy leather one, not like those frilly collars I’d seen on some pets in town. This one was army-built and just right for me. Conroy put it around my neck and buckled it. It made a nice jingling sound when I moved.

“Sorry it doesn’t have a tag on it. That’s ’cause you’re here unofficially,” Conroy said. “And now for a new trick.”

Conroy had already taught me some tricks. I knew Sit and Stay and Heel and Roll Over and Play Dead. I was ready to learn another.

He took some pieces of dried beef out of his pocket. I sat up tall. So far, so good.

“Present ARMS!” he said to me, just like Sarge said to him. He picked up my paw and touched it to the side of my head, just above my eye.

What exactly did this noodle-head have in mind? Did he expect me to hit myself in the face

like the rest of them? If he did, he had another think coming.

He gave me a piece of beef. I ate it.

He stood back. “Present ARMS!” he said. He stared hard at me.

Huh?

I stared hard back at him. He couldn’t possibly want what I thought he wanted.

The other young men in the barracks gathered around to watch.

“Give up. You can’t teach a dog to salute, Conroy,” one of them jeered.

“He doesn’t even

have

arms,” said another.

“You just wait. He’s a smart dog,” Conroy said. Once again, he demonstrated, bending his arm and hitting the side of his head.

“Let’s try again,” he said. “Present ARMS!”

If you can’t lick ’em, join ’em, I always say. This time, I lifted my paw and tapped the side of my

head. It was a little sloppy, but it was the best I could do with what I had.

The young men burst into cheers. They were so busy tackling Conroy, pounding him on the back, and messing up his hair that he forgot he owed me. I tapped him on the knee.