Dragonfly Falling

Dragonfly Falling

Shadows of the Apt Book 2

Adrian Tchaikovsky

For

Alex

A very big thank you to

everyone who’s encouraged and helped me over the last year, including Simon;

Peter and the folks at Macmillan; Al, Andy, Emmy-Lou and Paul; the Deadliners

writing group; and all the folks at Maelstrom and Curious Pastimes.

Stenwold

Maker

Beetle-kinden spymaster and statesman

Cheerwell

‘Che’ Maker

his niece

Tisamon

Mantis-kinden Weaponsmaster

Tynisa

his halfbreed daughter, formerly Stenwold’s ward

Salma

(Prince Salme Dien)

Dragonfly nobleman, agent of Stenwold

Totho

halfbreed artificer, agent of Stenwold

Achaeos

Moth-kinden magician

Scuto

Thorn Bug-kinden artificer, Stenwold’s lieutenant

Sperra

Fly-kinden, agent of Scuto

Balkus

Ant-kinden, agent of Scuto, renegade from the city of Sarn

Thalric

Wasp-kinden major in the Rekef

Ulther

Wasp-kinden governor of Myna, killed by Thalric

Reiner

Wasp-kinden general in the Rekef

Te

Berro

Fly-kinden lieutenant in the Rekef

Scyla

Spider-kinden magician and spy

Lineo

Thadspar

Beetle-kinden Speaker for the Assembly of Collegium

Kymon

of Kes

Ant-kinden master of arms in Collegium

Hokiak

Scorpion-kinden black-marketeer in Myna

Skrill

halfbreed scout in Stenwold’s service

Grief

in Chains

Butterfly-kinden dancer

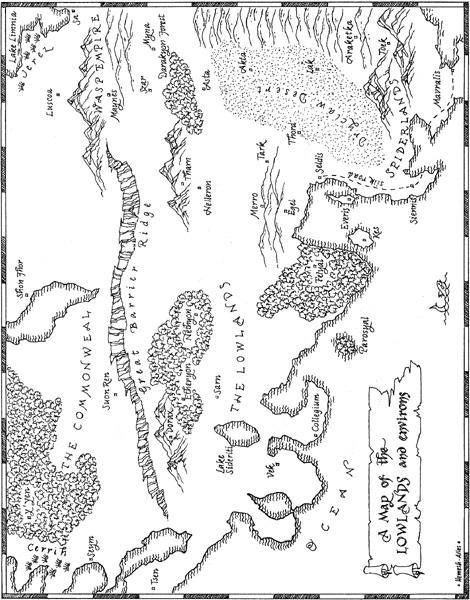

Places of import

Asta

Wasp-kinden staging post for the Lowlands campaign

Collegium

Beetle-kinden city, home of the Great College

The

Commonweal

Dragonfly-kinden state north of the Lowlands, partly

conquered by the Empire

The

Darakyon

forest, formerly a Mantis stronghold, now haunted and avoided

by all

Helleron

Beetle-kinden city, manufacturing heart of the Lowlands

Myna

Soldier Beetle-kinden city conquered by the Wasp Empire

Sarn

Ant-kinden city-state allied to Collegium

Spiderlands

Spider-kinden cities south of the Lowlands, believed rich and endless

Tark

Ant-kinden city-state in the eastern Lowlands

Tharn

Moth-kinden hold near Helleron

Vek

Ant-kinden city-state hostile to Collegium

Organizations

Arcanum

the Moth-kinden secret service

Assembly

the elected ruling body of Collegium, meeting in the Amphiophos

Fiefs

competing criminal gangs in Helleron

Great

College

in Collegium, the cultural heart of the Lowlands

Prowess

Forum

duelling society in Collegium

Rekef

the Wasp imperial secret service

For

many years the Wasp Empire has been expanding, warring on its neighbours and

enslaving them. Having concluded its Twelve-Year War against the Dragonfly

Commonweal, the Wasps have now turned their eyes towards the divided Lowlands.

Stenwold

Maker realized the truth of the Empire’s power when it seized the distant city

of Myna. Since then he has been sending out covert agents to track the progress

of an enemy whose threat his fellow citizens will not recognize.

Among

these agents are his niece Cheerwell, his ward Tynisa, the exotic Dragonfly

prince Salma, a humble half-breed artificer Totho . . . and staunchest of his

allies is the terrifying Mantis warrior Tisamon.

But

can their efforts bring the Lowlands to their senses before it is all too late?

The morning was joyless

for him, as mornings always were. He arose from silks and bee-fur and felt on

his skin the insidious cold that these rooms only shook off for a scant month

or two in the heart of summer.

He wondered whether he

could be accommodated somewhere else – as he had wondered countless times

before – and knew that it would not do. It would be, in some unspecified way,

disloyal

. He was a prisoner of his own public image.

Besides, these rooms had some advantages. No windows, for one. The sun came in

through shafts set into the ceiling, three dozen of them and each too small for

even the most limber Fly-kinden assassin to sneak through. He had been told

that the effect of this fragmented light was beautiful, although he saw beauty

in few things, and none at all in architecture.

His people had been

building these ziggurats as symbols of their leaders’ power since for ever, but

the style of building that had reached its apex here in the great palace at

Capitas had overreached itself. The northern hill-tribes, left behind by the

sword of progress, still had their stepped pyramids atop the mounds of their

hill forts. The design had changed little, only the scale, so that he, who

ought to expect all things as he wanted, was entombed in a grotesque, overgrown

edifice which never truly warmed at its core.

He slung on a gown,

trimmed with the fur of three hundred moths. There were guards stationed

outside his door, he knew, and they were for his own protection, but he felt

sometimes that they were really his jailers, and that the servants now entering

were merely here to torment him. He could have them killed at a word, of

course, and he needed to give no reason for it, but he had tried to amuse

himself in such capricious ways before and found no real joy in it. What was

the point in having the wretches killed, when there were always yet more, an

inexhaustible legion of them, world without end? What a depressing prospect:

that a man could wade neck-deep in the blood of his servants, and there would still

be men and women ready to enter his service more numerous than the motes of

dust dancing in the shafts of sunlight from above.

His father had taken no

joy in the rank and power that was his. His father had run through life, never

taking time to stop, to look, to think. He had been born with a sword in his

hand, if you believed the stories, and with destiny like an invisible crown

about his brow. The man in the fur-lined gown knew what that felt like. It felt

like a vice around the forehead forbidding him rest or peace.

His father had died

eight years ago. No assassin’s blade, no poison, no battle wound or lancing

arrow. He had just fallen ill, all of a sudden, and a tenday later he just

stopped, like a clock, and neither doctor nor artificer could wind him up

again. His father had died, and in the tenday before, and the tenday after, all

of his father’s children bar two, all of this man’s siblings bar one, had died

also. They had died by public execution or covert murder, for good reason or

for no reason other than that the succession, his succession, must be

undisputed. He was the eldest son, but he knew that the right of primogeniture

ran thin where lordly ambitions were concerned. He had spared one sister only,

the youngest. She had been eight years old then, and something had failed in

him when they presented him with the death warrant to sign. She was sixteen

now, and she looked at him always with the carefully bland adoration of a

subject, but he feared the thoughts that swam behind that gaze, feared them

enough to wake, sweat-sodden, when even dreaming of them.

And the order lay before

him still, to have her removed, the one other remaining member of his

bloodline. As soon as he had a true-blood son of his own it would be done. He

would take no pleasure in it, no more than he would take in the fathering. He

understood his own father’s life now, whose shadow he raced to outreach. Yet

how envied he was! How his generals and courtiers and advisers cursed their

luck, that he should sit where he did, and not they. Yet they could not know

that, from the seat of a throne, the whole weighty ziggurat of state was turned

on its point, and the entire hegemony’s weight from the broad base of the

numberless slaves, through the subject peoples and all the ranks of the army to

the generals, was balanced solely upon him. He represented their hope and their

inspiration, and their expectations were loaded upon him.

The servants who washed

and dressed him were all of the true race. At the heart of a culture built on

slavery there were few outlander slaves permitted in the palace, for who among

them could be trusted? Besides, even the most menial tasks were counted an

honour when performed for

him

. Of foreign slaves,

there were only a handful of advisers, sages, artificers and others whose

skills recommended them beyond the lowly stain of their blood, and though they

were slaves they lived like princes while they were still of use to him.

His advisers, yes. He

was to speak with his advisers later. Before that there were matters of state

to attend to. Always the chains of office dragged him down.

Robed now as befitted

his station, his brow bound with gold and ebony, His Imperial Majesty Alvdan

the Second, lord of the Wasp Empire, prepared to reascend his throne.

*

The Emperor kept many

advisers and every tenday he met with them all, a chance for them to speak on

whatever subject they felt would best serve himself and his Empire. It was his

father’s custom too, a part of that clamorous, ever-running life of his that

had taken him early to his grave as the Empire’s greatest slave and not its

master. This generation’s Alvdan would gladly have done without it, but it was

as much a part of the Emperor as were the throne and the crown and he could not

cut it from him.

The individual advisers

were another matter. Each ten-day the faces might be different, some removed by

his own orders, others by his loyal men of the Rekef. Some of his advisers were

Rekef themselves, but he was pleased to note that this was no shield against

either his displeasure or that of his subordinates.

Some of the advisers

were slaves, another long tradition, for the Empire always made the best use of

its resources. Scholarly men from conquered cities were often dragged to

Capitas simply for the contents of their minds. Some prospered, as much as any

slave could in this Empire, and better than many free men did. Others failed

and fell. There were always more.

His council, thus

gathered, would be the usual tedious mix. There would be one or two

Woodlouse-kinden with their long and mournful grey faces, professing wisdom and

counselling caution; there would be several Beetles, merchants or artificers;

perhaps some oddity, like a Spider-kinden from the far south, a blank-eyed Moth

or similar; and the locals, of course: Wasp-kinden from the Rekef, from the

army, diplomats, Consortium factors, members of high-placed families and even

maverick adventurers. And they would all have counsel to offer, and it would

serve them more often than not if he followed it.