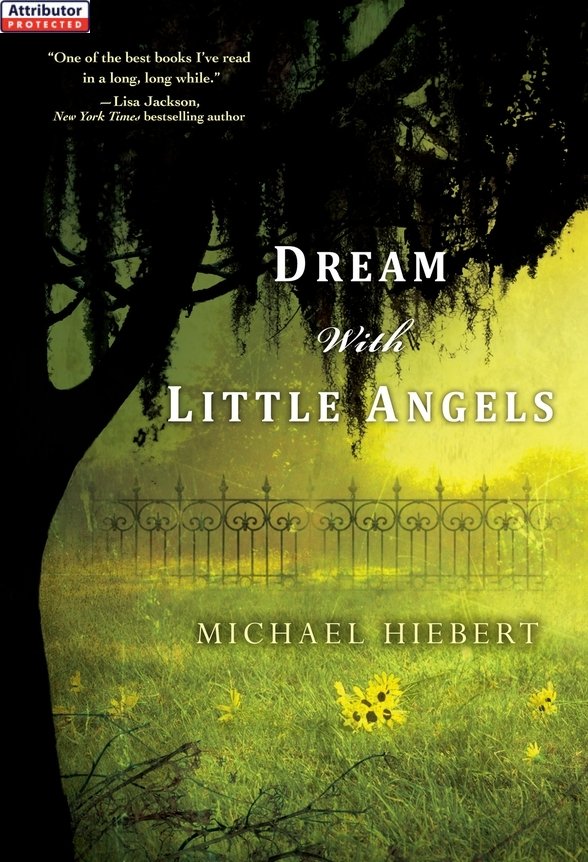

Dream With Little Angels

DREAM

With

LITTLE ANGELS

With

LITTLE ANGELS

MICHAEL HIEBERT

KENSINGTON BOOKS

www.kensingtonbooks.com

www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgments

P

ROLOGUE

C

HAPTER

1

C

HAPTER

2

C

HAPTER

3

C

HAPTER

4

C

HAPTER

5

C

HAPTER

6

C

HAPTER

7

C

HAPTER

8

C

HAPTER

9

C

HAPTER

10

C

HAPTER

11

C

HAPTER

12

C

HAPTER

13

C

HAPTER

14

C

HAPTER

15

C

HAPTER

16

C

HAPTER

17

C

HAPTER

18

C

HAPTER

19

C

HAPTER

20

C

HAPTER

21

C

HAPTER

22

C

HAPTER

23

C

HAPTER

24

C

HAPTER

25

C

HAPTER

26

C

HAPTER

27

C

HAPTER

28

C

HAPTER

29

C

HAPTER

30

A READING GROUP GUIDE

Discussion Questions

Copyright Page

Dedication

Acknowledgments

P

ROLOGUE

C

HAPTER

1

C

HAPTER

2

C

HAPTER

3

C

HAPTER

4

C

HAPTER

5

C

HAPTER

6

C

HAPTER

7

C

HAPTER

8

C

HAPTER

9

C

HAPTER

10

C

HAPTER

11

C

HAPTER

12

C

HAPTER

13

C

HAPTER

14

C

HAPTER

15

C

HAPTER

16

C

HAPTER

17

C

HAPTER

18

C

HAPTER

19

C

HAPTER

20

C

HAPTER

21

C

HAPTER

22

C

HAPTER

23

C

HAPTER

24

C

HAPTER

25

C

HAPTER

26

C

HAPTER

27

C

HAPTER

28

C

HAPTER

29

C

HAPTER

30

A READING GROUP GUIDE

Discussion Questions

Copyright Page

For my dad,

who never stopped believing in me.

Even when it all seemed so fantastic.

who never stopped believing in me.

Even when it all seemed so fantastic.

Â

and

Â

For my mom,

who has read nearly every single word

I've ever written. Even the bad ones.

who has read nearly every single word

I've ever written. Even the bad ones.

Acknowledgments

I'd like to thank John Pitts for his help in building the city of Alvin. I appreciate it so much that I even gave it his middle name. Also, Paul Tseng and kc dyer for being constant support systems. And I couldn't have done it without Julianna Hinckley, who read all these pages at least twice, and offered myriad suggestionsâall of which I implemented and all of which made this whole thing even better.

I have to mention my children: Valentine, Sagan, and Legend, who, I suspect like the kids of most authors, gave up a portion of their father to writing. The act of putting pen to paper (or, in my case, fingers to keys) is a severe balancing act with normal, everyday life that I don't know I'll ever master completely.

Then there's my girlfriend, Shannon, whose constant love and support keep me stable and at the computer cranking out words. I think she was the last one to do a read-through of the final manuscript. I couldn't have done it without you, babe.

And finally, I'd like to thank my mentors, Dean Wesley Smith and Kristine Kathryn Rusch, who taught me more about writing over the years than anyone else ever could have.

Â

Michael Hiebert

July 2013

British Columbia, Canada

July 2013

British Columbia, Canada

P

ROLOGUE

ROLOGUE

Alvin, Alabamaâ1975

Â

T

he grass is tall, painted gold by the setting autumn sun. Soft wind blows through the tips as it slopes up a small hill. Near the top of the hill, the blades shorten, finally breaking to dirt upon which stands a willow. Its roots, twisted with Spanish moss, split and dig into the loam like fingers. The splintery muscles of one gnarled arm bulge high above the ground, hiding the small body, naked and pink, on the other side. Fetal positioned, her back touches the knotted trunk. Her eyes are closed. Above her, the small leaves shake together as their thin branches shiver in the cold breeze. The red and silver sky gently touches her face. Her breath is gone. The backs of her arms, the tops of her feet, are blue. She's too small for this hill, too small for this tree.

he grass is tall, painted gold by the setting autumn sun. Soft wind blows through the tips as it slopes up a small hill. Near the top of the hill, the blades shorten, finally breaking to dirt upon which stands a willow. Its roots, twisted with Spanish moss, split and dig into the loam like fingers. The splintery muscles of one gnarled arm bulge high above the ground, hiding the small body, naked and pink, on the other side. Fetal positioned, her back touches the knotted trunk. Her eyes are closed. Above her, the small leaves shake together as their thin branches shiver in the cold breeze. The red and silver sky gently touches her face. Her breath is gone. The backs of her arms, the tops of her feet, are blue. She's too small for this hill, too small for this tree.

She's too small to be left alone under all this sky.

C

HAPTER

1

HAPTER

1

Twelve Years Later

Â

W

hen she was nearly fifteen, my sister Carry got her first boyfriend. At least that was my mother's theory when I asked why Carry suddenly seemed to live in a world I no longer existed in. She used to goof around with me and Dewey after school. Then, in the summer, she stopped paying much attention to us. After school started, she just ignored us altogether.

hen she was nearly fifteen, my sister Carry got her first boyfriend. At least that was my mother's theory when I asked why Carry suddenly seemed to live in a world I no longer existed in. She used to goof around with me and Dewey after school. Then, in the summer, she stopped paying much attention to us. After school started, she just ignored us altogether.

“I reckon she's shifted her interests,” my mother said, washing a plate at the kitchen sink. “She's round 'bout that age now.”

“Age for what?” I asked.

“For boys.” She sighed. “Now we're in for it.”

“In for what?”

“The hard part. My mama said my hard part started when I was thirteen, so I guess we should consider ourselves lucky.”

I didn't rightly know what she was talking about, but it sounded like something bad. “How long does the hard part last?” I asked.

“With me it lasted 'til I was seventeen. Then I got pregnant with Caroline.” She let out a nervous laugh. The Virgin Mother dangling from the silver chain around her neck swayed as she laughed. My mother always wore that chain. It had been a gift from my grandpa. “Let's just hope hers ends differently and not worry about what stretch of time it takes up, okay?”

I agreed I would, even though I still didn't rightly know what it was she was talking about. But I had other, more important things to worry about anyhow. A month ago, the Wiseners sold their house across the road because Mr. Wisener got work in Pascagoula, Mississippi. The house was purchased by a Mr. Wyatt Edward Farrow from Sipsey, who moved in shortly thereafter. My mother took me and Carry over two days later with a basket full of fresh-baked biscuits, golden delicious apples, and ajar of her homemade blueberry jam, and introduced us. The jam even had a pink ribbon tied around its lid. She made me carry the basket.

The door was answered by a tall, thin man, with dark brown hair trimmed short and flat. His most distinguishing feature was his square jaw that, from the look of it, hadn't been shaved in at least a few days. The rest of his facial features, like his forehead and eyes, were more or less pointed.

“I'm Leah Teal,” my mother said, “your neighbor from across the way. An' this here's Caroline, and this is my little Abraham.”

“Here,” I said, holding up the basket.

“I'm Wyatt Edward Farrow,” he said after a hesitation. I got the feeling he wasn't used to strangers showing up on his doorstep with baskets of biscuits, and he didn't know how to properly respond to our welcoming. When he spoke, his voice was quiet and pensive.

I don't think he trusted us.

“Pleased to meet ya,” he said, but by the way he said it, I had a hunch he didn't like meeting people much. There wasn't a trace of a smile on his thin lips. I was relieved when he finally took the basket from me, though. It was getting heavy with all them apples in it.

An uncomfortable silence followed that my mother broke by asking what it was Mr. Farrow did for work.

Something flashed in his gray eyes, and I got the distinct feeling Mr. Wyatt Edward Farrow didn't like being asked questions just as much as he didn't like strangers on his doorstep. “I'm a carpenter,” he said. “Work out of my home. Hope the noise don't bother ya none.”

“Hasn't yet,” my mother said with a warm smile.

Mr. Farrow didn't smile back. Something about him didn't sit right with me. It was like he was being sneaky or something. “Haven't been doin' nothin' yet,” he said. “Still settin' up my tools in the garage.”

“Well, I'm sure it will be fine,” my mother said.

“Sometimes I work in the evenings,” Mr. Farrow said. He narrowed his eyes and looked from me to Carry as though daring us to tell him we took exception to evening work.

“I usually do, too,” my mother said, “so that should work out fine.” That my mother just told this suspicious-looking stranger that me and my sister spent most nights alone in our house didn't settle so good with me at all. I was glad when she followed by telling him what she did for work. “I'm a police officer. My schedule's a bit irregular too, at times.” I saw a slight twitch in one of his eyes when she relayed this information, though he hid his reaction well.

Three days later, Mr. Wyatt Edward Farrow finished setting up his tools. The sun had just dropped behind my house and me and Dewey were in the front yard trying to see who could balance a rock on the end of a branch the longest. It was an almost hypnotic exercise, especially with the quiet singing of the cicadas drifting by.

That was until a loud roar suddenly ripped through the evening.

Dewey and I both jumped, our rocks tumbling to the ground. My heart raced against my chest. Trembling, we both stared across the road. Behind Mr. Farrow's garage door, something had sprung to life.

“Sounds like a mountain lion,” Dewey said, his eyes wide. Dewey was my best friend for as long as I could remember. He lived eight houses down Cottonwood Lane, on the same side of it as me, and we were almost exactly the same age. His birthday came two days before mine.

My heart was slowing back down to normal again. “Must be a saw or somethin',” I said. I told him about Mr. Farrow being a carpenter. “Least that's what he claimed. At the time, I didn't believe him.”

“Why not?”

I shrugged. “He just seemed to me like he was lyin' about it.”

“Why would he lie about somethin' like that?”

“I don't know. I just didn't trust him.”

“Sure is loud.”

With a whir, the sound stopped. Me and Dewey stood there in the dim purple light of early evening, watching the garage door expectantly. From underneath it shone a narrow strip of white light. Sure enough, a few minutes later something else started up and we both jumped again. This thing was higher pitched than the other and even louder.

“Sounds like a hawk,” Dewey said.

“Lot louder than a hawk,” I said.

That night, me and Dewey heard ten different animals screaming from inside that garage. For the week following, we spent most of our evenings lying in my front lawn, our chins propped up on our hands, staring across the road, listening to Mr. Farrow work and speculating on what it was he could possibly be building. Far as we could tell, he never left that garage. The windows in the rest of the house were always dark.

“Part I can't figure out,” Dewey said, “is when does he go to the bathroom? We should at least see lights come on

sometime

for that, shouldn't we?”

sometime

for that, shouldn't we?”

“Maybe he just goes in the dark.”

“Maybe.”

A few days after that, Dewey made the observation about the roadkill.

We were coming home from school when he said it. Dewey and I had walked to school together for as long as I could remember, but that would all end after this year. Being so small, Alvin had only an elementary school. For middle school and high school, you had to go down to Satsuma. For four years, Carry spent over two hours total on the bus going to and from school and I listened to her complain about it every day. Well, until this year. Now that she was the right age for boys, she didn't talk much at all to me anymore. I wasn't looking forward to going to middle school. I enjoyed my and Dewey's walks.

Autumn was doing its best to settle in. We walked along Hunter Road, beneath the tall oak trees, sunlight filtering down on us through their almost orange and yellow leaves. Neither of us had said much since leaving school. I was hitting the ground in front of me with a piece of hickory I found a couple blocks back, and Dewey had his head down and his hands stuffed into the pockets of his jeans. By the way he walked, he seemed to me like he was thinking hard about something, and I didn't want to interrupt.

Finally he looked up and said, “Have you noticed anything different lately?”

I thwacked the trunk of an oak with my hickory. “Different like what?” I asked.

He hesitated like he was thinking whether or not to tell me. “I just . . . a week ago I started noticing there weren't no dead animals on the road anymore.”

I laughed, but he was serious.

“So I have been payin' attention to it ever since. And for a week now, I ain't seen a single piece of roadkill anywhere.”

“I guess the raccoons are getting smarter,” I said and laughed again. I reckoned this was a strange thing to have spent so much time over.

Dewey stopped walking, so I did, too. “Abe, you don't think it's strange? For a whole week I ain't seen a single dead squirrel, chipmunk, snake, possum, nothin'. Hell, not even a skunk. Even when old Newt Parker was still alive, you still saw at least a couple skunks most weeks.”

“Newt Parker never really ate roadkill,” I told him. “That was all just third grade stories going around.”

“He did so. Ernest Robinson said he saw so himself. Said he was riding his bike past the Parker place one afternoon and old man Parker was sitting right there on a chair out in the front lawn munching on road-killed raccoon.”

“Ernest Robinson is full of crap. How did he know it was 'coon?”

“Said it looked like one,” Dewey said. “What else looks like raccoon but raccoon?”

He had a point there, but I still wasn't convinced. “How did he know it was road killed?”

Dewey had problems answering that one. Eventually we started walking again and I resumed hitting the ground with my hickory stick. “I still think it's strange that I haven't seen any for a week,” he said.

“You want me to go find a rabbit and throw it in front of a car for you?” I threw the hickory into the woods as we turned down our street.

“I just think it's weird, is all,” he said, and that was the end of it.

Except after Dewey had brought it to my attention, I couldn't help but start looking for roadkill everywhere I went. Soon I understood Dewey's concern. After only three days of seeing none, a feeling of uneasiness began creeping into my stomach. By the time a whole 'nother week went by, we knew we had stumbled onto evidence of foul play of some sort. Only neither of us could come up with an idea of what sort of foul play could possibly result in cleaning up dead animals from every street in Alvin.

It was a mystery that wove through my brain nearly every minute I was awake. While I ate breakfast, while I sat through school, always. Even while Dewey and I laid in the grass staring at the strip of light beneath Mr. Farrow's garage door on the side of his darkened house, and pretended to ponder what he might possibly be constructing, we were actually trying to puzzle out the roadkill phenomena. When I finally went to bed, at least an hour was spent staring up at my ceiling while my mind made one last attempt at solving the riddle before shutting down for the day. Neither me nor Dewey could come up with any sort of explanation for what we were witnessing or, I suppose,

weren't

witnessing would be more precise. Even if an entire

family

of Newt Parkers moved into Alvin, they couldn't possibly eat up all the roadkill in the whole town. Nothing about it made any sense.

weren't

witnessing would be more precise. Even if an entire

family

of Newt Parkers moved into Alvin, they couldn't possibly eat up all the roadkill in the whole town. Nothing about it made any sense.

Then, four days later, Mary Ann Dailey disappeared.

Other books

Something New by Janis Thomas

Night Swimming by Laura Moore

Magia para torpes by Fernando Fedriani

Santa's Pet by Rachelle Ayala

Georgia on My Mind and Other Places by Charles Sheffield

Blood and Sympathy by Clark, Lori L.

That's Amore! by Denison, Janelle, Carrington, Tori, Kelly, Leslie

Worth Any Price by Lisa Kleypas

The Outcast by Michael Walters

Belle of Batoche by Jacqueline Guest