Dreamer

Table of Contents

- DREAMER: A NOVEL OF THE SILENT EMPIRE

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- PROLOGUE

- CHAPTER ONE

- CHAPTER TWO

- CHAPTER THREE

- CHAPTER FOUR

- CHAPTER FIVE

- CHAPTER SIX

- CHAPTER SEVEN

- CHAPTER EIGHT

- CHAPTER NINE

- CHAPTER TEN

- CHAPTER ELEVEN

- CHAPTER TWELVE

- CHAPTER THIRTEEN

- CHAPTER FOURTEEN

- CHAPTER FIFTEEN

- CHAPTER SIXTEEN

- CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

- CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

- CHAPTER NINETEEN

- CHAPTER TWENTY

- CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

- CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

- CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

- CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

- CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

- CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

- CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

- CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

- CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

- CHAPTER THIRTY

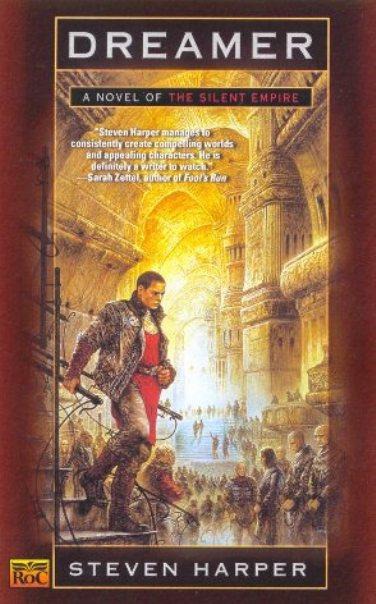

DREAMER: A NOVEL OF THE SILENT EMPIRE

by Steven Harper

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to offer heartfelt gratitude Sarah Zettel for her invaluable contributions to this novel. Without her creativity and insight (and ice cream supply), this book would not exist. Thanks, Comrade!

I would also like to thank the Untitled Writers Group of Ann Arbor (Erica, Jonathan, Karen, Lisa, Sarah, and Sean) for their patience in reading chapter after chapter and offering comment after comment.

PROLOGUE

PLANET RUST

For one thing to begin, another must end.

—Rustic Proverb

In the end, they walked to Ijhan. Vidya Vajhur started with swift steps, but Prasad slowed her down.

“You’ll tire quickly at that pace,” he told her. “We have a long way to go.”

Vidya nodded. She set her shoulders more firmly into the shoulder harness Prasad had made for the wheelbarrow and forced herself into a steady trudge. The wheelbarrow was piled with clothing, a tent, food, and other necessities. It was hard to think of it as everything she owned, so she didn’t.

Gravel crunched as Vidya walked. Beside her, Prasad pushed a cart containing the rest of their food. Hidden at the bottom were a few trinkets he said he didn’t want to leave behind. One was their wedding knot. Another was a set of red data chips, red for medical histories and gene scans. Prasad had tried to slip them into the cart without her seeing. Vidya had wordlessly her lips. Prasad’s cart was topped by a crate of a dozen quacking ducks, the only animals unaffected by the Unity blight.

“Imagine if the blight had left the kine,” Prasad had said. “Too valuable to leave and too difficult to take on the road. We’re lucky there.”

Leave it to Prasad,

Vidya thought wryly,

to find blessings in a pile of horse shit.

The harness bit into Vidya’s shoulders and she spared a glance at her husband of five years. He was a head taller than she was, with brown skin to match her own. His black hair had gotten shaggy of late. Dark whiskers dusted chin and cheeks, though he had shaved only yesterday, and curly hair coated his strong forearms as they strained against the hand cart. His beautiful black eyes were lined with stress and strain, though he was barely twenty-five.

Vidya’s eyes were a lighter brown beneath thin brows and a high forehead. Her face was a pleasing oval, and her body was long and lean. Too lean.

The crated ducks on Prasad’s cart quacked in annoyance. Vidya wished they would shut up. They were getting a free ride, weren’t they? She’d trade places with them in a second. It would be nice to be a duck. You could root around in a quiet pool to find food, and if there wasn’t any, you only had to fly somewhere else.

She found she was striding again and forced herself to slow down. Her legs wanted to carry her fast and far so she wouldn’t be tempted to look back at their ruined farm. She kept her eyes firmly on the gravel road before her. Watching out for the blast craters that made wheeled transport impossible was a good excuse to avoid looking at the fields. She could not, however, block out the smell. Every breath brought her the damp, moldy stench of standing crops destroyed by the Unity blight. Sometimes she caught a whiff of rotting meat, and once she smelled burned feathers. This made her speed up, and Prasad lengthened his own pace. Without a word, they pushed on as fast as they dared until the smell faded. Vidya heaved a soft sigh. Chickens mutated the blight into a form that attacked humans, and burning feathers could only mean a poultry farm someone was trying to cleanse. Except in that one instance, the blight—actually a series of diseases—left humans alone. Only now was Vidya realizing how that was, in some ways, even more horrible.

They trudged on, Vidya’s eyes on the ground, until Prasad gasped. Vidya looked up. They had reached the main road, and it was in worse condition than the one they had been traveling. Flyers from the Empire of Human Unity had bombed and strafed it thoroughly. Craters pocked some places, piles of shattered pavement blocked others. It was passable, but only with difficulty. Prasad, however, was looking straight ahead. Vidya set the wheelbarrow down with an angry thump.

“This is a treat!” she cried. “A gift!”

“Hush,” Prasad murmured. “We shouldn’t call attention to ourselves.”

Vidya glared at him, then swallowed her sharp retort. Sarcasm wouldn’t improve the situation, and it wasn’t Prasad who deserved her anger.

“What do you think we should do?” Vidya asked at last. “I have no ideas.”

Prasad shrugged. “What else can we do?”

He lifted the handles on the hand cart and trudged forward. The ducks quacked again. Vidya hesitated, then set her shoulders, hefted the wheelbarrow, and joined him.

The streaming mass of people on the road made grudging space for them. Thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, crowded the broken pavement. Most carried bundles or pushed carts and barrows. Many were injured. All were heading toward Ijhan.

The crowd shuffled along in eerie silence. Those who spoke did so in subdued voices. Occasionally a baby whimpered or a small child cried, but the sounds were quickly hushed. It was as if the throng feared being noticed.

“They must have heard the rumors, too,” Vidya murmured. Her eyes flicked left, right, forward, behind, constantly scanning the crowd.

“Relief in Ijhan,” Prasad agreed softly. “I wish we could’ve checked with Uncle Raffid to see how true it is. I wish—”

“You make a hundred wishes before breakfast,” Vidya said. “Wishing will not take the networks from the Unity’s hands or make it possible to call—”

“Poultry!” shrieked a voice. “My god—

birds!”

Vidya’s head snapped around. A silver-haired man was staring at Prasad’s duck crate in horror. Prasad blinked. The people around them began to draw away.

“The blight!” the man screeched. “They’ll bring the blight!”

He lunged for the crate, intending to smash it, but Vidya was already moving. Her hand snatched a small bundle from the wheelbarrow and whipped the cloth away.

“Stop!” she barked. “Or die.”

The man froze. So did the people around him. After a split-second, the crowd edged away, leaving the man in an ever-widening circle. Vidya held a short rod in rock-steady hands. It glowed blue, and a single spark crackled at the end.

“This is an energy whip for herding kine,” she said, standing in the wheelbarrow harness. “At half power it stuns a full-grown bull. It is now set to full. Leave the ducks alone.”

“The blight—” the man gasped.

“—is only found in chickens,” Prasad said in his soft voice. “Ducks don’t carry it.”

“Back away,” Vidya repeated. “I will press the trigger in three...two...”

The man fled into the crowd. Vidya watched until he was out of sight. Then she slid the whip into her belt, shrugged her shoulders in the harness, and continued on her way. Prasad followed. The crowd watched for a moment, then slowly closed about them.

“My wife has fine reflexes,” Prasad observed. “It did not occur to me that our own people would wish to harm us or take our property.”

“My husband is trusting,” Vidya said, not sure at that moment whether she was annoyed at him or fond of him. The adrenaline rush was wearing off and her hands would have been shaking had they not been gripping the wheelbarrow staves.

Prasad reached over and squeezed her hand twice. She smiled at him. The gesture, born on their wedding night, had originally meant “I love you,” but it had, over the years, become a more all-purpose signal of anything positive. Here, Vidya took it to mean “you did well.”

Hours passed. Hunger pinched Vidya’s stomach—she and Prasad had skipped breakfast to save food—and she was sweating even though a thick layer of clouds blocked the sun. It was warm for early fall. The world of Rust had an even, temperate climate because it had no moons to stir wind and water to anything greater than a balmy breeze or gentle rain. Vidya had dim memories of torrential rains and rushing winds, but after her parents emigrated to Rust, all her experiences with weather involved slow, easy swings from sun to clouds to rain and back again. Now the above-average temperature made her uneasy. Had the Unity done something to the weather as well as spreading the blight? Vidya’s stomach growled, and a hunger headache coiled behind her forehead.

“We need to eat,” Prasad said. “Perhaps over there.”

They guided cart and barrow to the edge of the road and into what had been a hayfield. Mushy stalks squelched under Vidya’s shoes, and the fetid smell lessened her appetite. A waist-high stone wall divided the field in half, however, and this was Prasad’s goal. Other people were taking advantage of the wall as a place to rest, but Prasad, Vidya noticed with satisfaction, warily kept his distance from them. They wheeled their respective conveyances to a likely spot and pulled themselves up to the wall’s bumpy top. Vidya groaned as her weight left her aching feet.

“May I sit with you?”

The whip was already in Vidya’s hand and pointed at the speaker. It was a woman with a pack on her back and two small children at her side. Vidya didn’t lower the whip.

“Of course,” Prasad said gently. “Do you need help?”

“Prasad,” Vidya warned. “We can’t—”

“Our old community was destroyed,” Prasad replied. “If we wish to survive, we must build a new one.”

“We can be three more pairs of eyes to watch for thieves.” The woman nodded at Prasad’s cart. “Or duck-nappers.”

A laugh popped from Vidya’s mouth before she could stop it. She motioned for the woman and her children to sit. The woman’s name was Jenthe. The children were her sister’s.

“My sister was Silent,” Jenthe continued. “Her owner planned to hide just her—not her husband or children—in case the Unity won the war. I think she was planning to run away, but then she and her husband disappeared. Now we’re traveling to Ijhan because they have food.”

Vidya shot a glance at Prasad’s cart. “Do the children belong to your sister’s owner?” she asked bluntly. “Are they Silent, too?”

“Vidya,” Prasad said. “We don’t need to be rude.”

“We need to know,” Vidya replied. “If the children are Silent, they’re valuable.”

Jenthe pulled both children closer to her. They looked at her with wide eyes. Vidya sighed. Jenthe’s gesture had answered Vidya’s question as clearly as a shout.

“I’m not going to take them from you,” Vidya said quietly. “But someone else might. It isn’t duck-nappers we have to worry about.”

“I’ve worried about that since we left,” Jenthe said, and changed the subject. “Have you heard if we’ve surrendered to the Unity yet?” She rummaged around in her backpack and took out half a piece of flat bread. She divided it between the children but took none for herself. Vidya sighed and waited. On cue, Prasad offered Jenthe a piece of their own flat bread. Jenthe refused, but finally accepted after minimal pressure from Prasad. Vidya mentally went over their tiny store of food, all that remained after six months of bombs and blights. It would take them three days to reach Ijhan, maybe four, and they could do it without slaughtering the ducks if they ate two small meals a day. If they fed three more mouths, though, they’d have to eat the ducks, and Vidya had been counting on using them as trade goods. She had a feeling that the money they carried wouldn’t be worth much.

“I haven’t heard of surrender,” Prasad was saying. “Perhaps we’re winning.”

Vidya glanced at the river of refugees on the road and suppressed an acidic remark. There really was no point. Words wouldn’t change their situation.

“May we sit with you?” said a cautious voice. Vidya sighed and chewed her bread.

It took four days to reach Ijhan. In that time, their group had grown to twenty people. Prasad’s crate had four ducks left.

Vidya had visited Ijhan half a dozen times in her life. She remembered it as a sprawling city of trees and low buildings. It still was, but now a refugee camp had sprung up around it like a moat around a castle.

“They aren’t letting anyone in,” Mef reported. He was fourteen and on his own now. Prasad charged him with scouting ahead because he still had energy for it and he had a knack for gathering information. “They’ve built sandbag walls around the whole city. Trucks came out with food four days ago, but that’s been it.”

A murmur went through the group and Vidya bit her lip. Counting the ducks and Gandin’s two geese, the group had enough food for two or three days. The filter on Vidya’s water bottle would also give out soon, and she didn’t want to think about what filth had accumulated in the ponds and streams. The area around the city already smelled like a sewer.

“There aren’t letting

anyone

in?” Prasad asked. The desperate note in his voice made Vidya’s heart lurch. The past several days had been hard on all of them, but it showed most on Prasad. The skin around his eyes sagged with hunger and fatigue and he spoke little. When they curled next to each other to sleep, she had felt the tension in his body grow with each passing night. She wanted to comfort her husband, this strong man, but she didn’t know how to do it other than to stand beside him.

Mef shook his head. “No one goes in. The famine is just as bad in the city.”

Vidya took Prasad’s hand and squeezed twice. He squeezed back, but the gesture lacked any strength.

Vidya clasped her hands around her shins beneath the overturned hand cart. Soft, gentle rain washed down from the sky to form soft, gentle mud. The latrine pits had already overflowed. Turds mixed with dirt and piss mixed with water until it was impossible to tell one from the other in a mix like sloppy pudding. Cholera and dysentery swept the camps. Babies and young children, already weak from lack of food, fell sick and died in mere hours. Vidya’s last meal had been a handful of beans four—or was it five?—days ago. They had cost her and Prasad the tent. The only water Vidya had was what she could catch from the sky. Her skin was waterlogged and flaccid, with white sores Prasad said were a form of mold.

At first, all Vidya had been able to think about was food. Thoughts of tender goose, crunchy felafel, sizzling beef, and hot flat bread with sweet honey bombarded her until she thought she would go insane. Now she wasn’t thinking of food, or anything else. Her stomach no longer cried out and it had long ago become a dull ache inside her. Prasad had left several hours ago on an errand he refused to discuss, but Vidya didn’t have strength to care. She stared into the rain from the scant shelter of Prasad’s cart, not even wondering what would happen next.