Dreamers of a New Day (30 page)

Read Dreamers of a New Day Online

Authors: Sheila Rowbotham

(National Co-operative Archives)

Control over communications was recognized as vital, not only for governing a democracy but for persuading people to reorient their everyday desires. Advertisers were learning how to market not only things, but intangibles like aspirations and dreams. Advertising and the movies, as Christine Frederick astutely noted in

Selling Mrs Consumer

in 1928, were fostering a yearning for youth, beauty and leisure among a wide stratum of women. Blessing the arrival of the time-saving tin can, Frederick turned her attention to the beauty industry, reporting how worries about ‘physical charm’ were driving a huge consumer industry.

‘Enough lipstick is sold per year now – about two sticks per woman – to reach from New York to Reno.’

66

She also detected a newly emergent trend, ‘Selling Health and Naturalness’ through ‘toilet preparations’, predicting that ‘We are going to hear more about the health and beauty idea’.

67

Frederick, with her sharp eye for shifts within popular culture, was intrigued that so many American women were refusing to ‘give up their youth as their grandmothers did, at 35 or so’. She detected ‘flappers of sixty-four’ discovering that ‘Cosmetics, plus clothes, can do marvels’.

68

Utopia had been given a price tag.

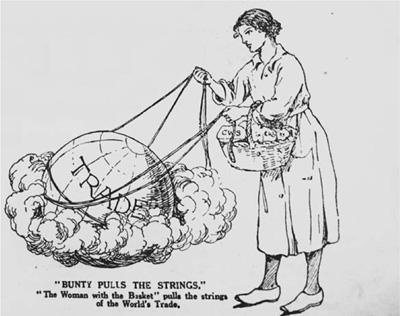

Mrs Consumer, in the kitchen or in front of the mirror, was the good/bad fairy in the new economic scenario. She could spend and keep the world of business happy, or she could wield, in Frederick’s words, ‘an ominous ruthless power’ by refusing to buy, as she had done in the consumer boycotts.

69

In both countries a powerful economic and ideological lobby was pushing for private household services and goods, along with individual home-ownership. This was not simply a matter of filling the cash tills; consumption was the site on which contesting ideologies were being fought out. Symbolically, in 1931 Ethel Puffer Howes’s co-operative housekeeping institute collapsed. She was, however, invited to participate in President Hoover’s national conference on Home Building and Home Ownership, which Dolores Hayden describes as ‘dedicated to a campaign to build single-family houses in the private market as a strategy for promoting greater economic growth in the United States and less industrial strife’.

70

Post-war radicals and reformers adapted their demands to the changing context with an amalgam of social measures, and efforts to raise the capacity of the working class to consume. In her 1923 study

A Theory of Consumption

, the American economist and labour educator Hazel Kyrk argued for the extension of ‘socialized consumption’. Pointing to services which were already accepted as public – from street-cleaning and garbage collection to libraries, parks and swimming pools – she proposed adding further public utilities. Eschewing a ‘city housekeeping’ approach to social consumption, she linked her civic vision to redistributive policies, favouring a minimum wage over price controls.

71

Influenced by the under-consumptionist theories of the economist J. A. Hobson, British socialists also put forward various suggestions for increasing workers’ spending capacity: minimum wages and ‘living’ wages, along with state allowances, the endowment of motherhood and, more radically, guaranteed basic incomes. In the early 1920s the

Independent Labour Party related the living wage to the specific needs of women and children; by the end of the decade it would be expressing a general concern for the ‘unemployed’.

72

A proposal for a citizens’ income was adopted in 1918 by the small revolutionary group, the Socialist Labour Party, which demanded maintenance for all adults, with extra amounts for parents. Like the endowment of motherhood, the demand for a citizens’ income was encouraged by the wartime maintenance grants paid to the wives of men in the armed forces, which seemed to link state policy and standard of living.

73

Women reformers continued to bring differing hopes to the endowment of motherhood. While Eleanor Rathbone saw it as a means for women to acquire an independent income, others thought the measure would help to redistribute wealth and boost purchasing power.

The move towards strategies which sought to increase working-class income through state benefits avoided the awkward problems the co-operative housekeepers had confronted in telling others how they should live. On the other hand, it also reduced the possibilities of altering the social organization of domestic activity and daily life. Ethel Puffer Howes’s warning that consumer goods could not tackle all aspects of domestic labour went unheeded: ‘Quite apart from the fact that millions of us are not able to command them, the washing machine won’t collect and sort the laundry, or hang out the clothes, the mangle won’t iron complicated articles, the dishwasher won’t collect, scrape and stack the dishes; the vacuum cleaner won’t mop the floor or clean up and put away’.

74

Also disregarded was the voice of the American ‘muckraking’ journalist Louise Eberle, writing in

Collier’s

magazine in 1910 on the yellow powder ‘Eg-o-lene’, which substituted for eggs in ‘egg custard’. In Eberle’s opinion, modern food was ‘made to sell and not to eat’. She grimly warned of worse to come: ‘Foodless food is not a passing fad, but is the sinister expression of the genius of the present day of the horseless carriage, the birdless wing, and the wireless message. What the human system thinks of it the bodies of the next generation will tell.’

75

With hindsight, this pessimism has taken on a prophetic ring.

8

Labour Problems

‘I love you – but I love my work better’, a decisive Beatrice told Sidney Webb during their courtship.

1

In 1887 she had already decided to make work, rather than personal relationships, the core of her existence; her aim was to achieve ‘the ideal life for work’.

2

Webb would pursue her autonomous course through the dangerous shoals of desire and marriage, determined she was not going to fade, like other intelligent women of her acquaintance, into living only for the work of her husband. Along with the other pioneering women of the 1880s who sought emancipation through work, she was heading into an uncharted future.

Middle-class rebels like Webb were confronted by contradictory attitudes. In aspiring to the public recognition which educational endeavour and intellectual or professional work promised, they were echoing the high value placed on work in Victorian society. They had been shaped by a culture which ascribed virtue to work while delineating a separate female destiny for women through marriage. Work promised a sense of self-worth as a human being which transcended gender; it represented a means of securing a new identity as an individual. Yet, because a feminine identity was so bound up with domesticity and service to kin, the desire to work involved a certain defiance of gender boundaries.

Many of the middle-class dissidents had been reared in families which believed in education and social service, and they brought high ideals to the limited opportunities on offer. Yet the reality of their working lives proved rather more grubby; most of the middle-class women who struggled so hard for higher education and employment were in fact condemned to what Sidney Webb in 1891 called ‘routine mental work’.

3

C. Helen Scott, who sought to deepen her education by attending University Extension lectures, urged workers in 1893 to accept

that ‘there are toilers in middle-class life too, who leave the study and the desk, the school and the sick-room, and the social weariness of the drawing-room, with bodies as tired, with brains more weary, but with minds and hearts as hungry and eager as those of their, so-called, humbler brethren . . .’

4

Not all new women who struck out on their own were from well-padded upper-middle-class families. Eleanor Marx Aveling, who earned a living from journalism and translation, was badly paid and faced considerable insecurity. Her childhood friend Clara Collet, who like Beatrice Webb worked on Charles Booth’s social survey,

Life and Labour of the People

(1889), was the daughter of a principled radical Unitarian who had scraped together a living from journalism and music teaching. She, in turn, would find that being a jobbing intellectual curtailed her choices. Around 1900 she was recording in her diary, ‘Gave five lectures on rent at Toynbee’, adding, ‘And what I am going to live on next year I don’t in the least know.’

5

In 1902 Collet was drawing on her own experience when she noted in

Educated Working Women

that the types of employment middle-class women could enter were overstocked and underpaid. Her advice to the next generation was to become designers, chemists, foreign correspondents and factory managers.

Whatever problems beset educated working women, those of the uneducated were far worse. Concerned by the lack of any collective safeguards for women, and inspired by the organizations formed by American women craft workers, Emma Paterson, a book-binder, had started the Women’s Protective and Provident League in 1874; this later became the Women’s Trade Union League. The League incorporated the welfare services provided by workers’ friendly societies in a form of social unionism which gained middle-class support. Its co-operative offshoots included a Halfpenny Savings Bank, the Women’s Labour Exchange, a workers’ restaurant and a swimming club.

6

Like many ‘new women’, the Leeds socialist and feminist, Isabella Ford, saw work as a vital form of self-expression, but recognized such an ideal was remote from the lives of the Northern working-class women she knew in the textile and clothing factories of Bradford and Leeds. Their conditions convinced her of the need for trade unions and women factory inspectors.

7

Along with several other middle-class ‘new women’, including Eleanor Marx Aveling, Ford encouraged women workers to join the militant New Unionism of the late 1880s and early 1890s. Unlike the craft unions, this democratic trade unionism was open to the unskilled and to women.

The difficulty of organizing women workers led some of their middle-class supporters to adopt other forms of action to complement union organizing. In 1889 the socialist Annie Besant, who the previous year had helped to publicize a strike by East London match women, persuaded the Tower Hamlets School Board to only tender with firms that did not exploit their workers. Besant and the Women’s Trade Union League leader, Emilia Dilke, challenged the firm of Eyre and Spottiswoode which produced cheap bibles, pointing out the irony of women folding bibles for wages that were so low they could be forced into prostitution. The following year the WTUL Secretary, Clementina Black, would extend this precedent by getting the London County Council to determine a fair wage for clothing workers producing its supplies. Not only was this innovatory in proposing that the consumer rather than the employer should decide on pay, she was asserting that women workers were entitled to a living wage.

8

The women Black was defending were not only non-unionized but working, like many others, in what were loosely termed ‘the sweated trades’. High rents discouraged the growth of large factories in the larger cities, so a flexible network of sub-contractors put out the work to small ‘sweatshops’ or to women working in the home. In London, immigrant Irish and Jewish women were often forced to take on this kind of low-paid and insecure work. Homework was vital for those unable to seek employment outside, such as mothers and the infirm, who would often be helped by children. Though attempts were made to organize homeworkers, these scattered and vulnerable workers remained at the very bottom of the labour market. Their predicament defeated the efforts of such resolute new women as Helena Born and Miriam Daniell in Bristol, Eleanor Rathbone in Liverpool and Isabella Ford in Leeds. From the 1890s the WTUL began to adopt a strategy of bolstering organization by lobbying for state intervention.

Labour-intensive ‘sweated’ work proliferated in American cities as well as in Britain. The radicals and reformers who exposed its existence and investigated its extent were troubled to find not only adults but children working at home and in small workshops. The Illinois Woman’s Alliance was formed in 1888 after a journalist’s exposure of ‘City Slave Girls’ in the garment industry. It included social reformers as well as socialists keen to expose child labour along with the low pay, long hours and health hazards associated with women’s ‘sweated’ work. In 1891

two members of the Alliance, Elizabeth Morgan and Corinne Brown, made their way down a dark, narrow passage in Chicago. After lighting matches to see, they reached a basement workroom where ten men, four girls and two little children under ten worked on trousers and cloaks. Morgan reported that ‘Lack of air, smell of lamps used by the pressers, and stench of filth and refuse made this a most horrible hole’.

9

It was typical of the small clothing workplaces.