Duke (26 page)

Authors: Terry Teachout

Ellington also recorded a two-minute promotional interview with Percy Brooks, the editor of

The Melody Maker

and the man who had dubbed Louis Armstrong “Satchmo” in 1932. “Souvenir of Duke Ellington” is a studied performance in which both men are almost certainly reading from a script. First we hear Ellington tinkling away at “Mood Indigo” on the studio piano, after which Brooks asks him a series of obvious questions to which he makes stilted replies: “Just as soon as possible, we will be back again. If it doesn’t turn out to be an annual trip, I will be the most disappointed man in the world. . . . It has been positively embarrassing at times to be asked the most analytical questions about work which I have nearly forgotten by now.” Even so, it is touching to listen to their chat, in which Brooks treats Ellington with manifest respect, in much the same way that it is touching to listen to “Ellingtonia,” a snappy three-minute medley of “Black and Tan Fantasy,” “It Don’t Mean a Thing,” “Mood Indigo,” and “Bugle Call Rag” that Jack Hylton and his all-white dance band recorded in London four months later.

On July 24 Ellington and his men left for a brief tour of the continent, playing one concert in Holland and three in Paris at the Salle Pleyel, the two-thousand-seat hall where Armstrong had made his Paris debut. Hugues Panassié was there, and was impressed: “Duke directed his orchestra in lordly fashion. At the piano, with a quick, elegant gesture, he would lift an arm from time to time to indicate a nuance to his musicians. The ease and nobility of his manner . . . were indescribable.” Dick de Pauw, the band’s tour manager, set down an equally vivid pen portrait of the offstage Ellington:

Duke never shows the slightest sign of life before five o’clock in the evening. Indeed, this business of rousing him and getting dressed in time for the first house was the most bewildering task of the tour. . . . I discovered that Duke suffered from a kind of nervous complex in the matter of time, because, no matter how early he happened to be, he would never commence to dress until the last possible second, and then when everybody around was all worked up and yelling, “The show’s on!” he would scramble on his coat while running down the corridor and, with that bland smile of his, stride onto the stage and commence playing—all in one breath as it were. He simply could not face the ordeal of being dressed-up and waiting back-stage all ready for the curtain to rise—he had to run on in a whirl of excitement in order to get the right mood for that opening number.

Needless to say, there was also time for carousing, including a visit to Le Chabanais, the luxurious Paris brothel whose celebrated patrons included Salvador Dalí, Guy de Maupassant, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and King Edward VII. Ellington and Irving Mills went there together, accompanied by Mills’s interpreter and an unnamed companion whom the composer later described as “some society woman, one of those dowagers . . . from America.” The visit was the source of an oft-told anecdote that Mercer thought to be apocryphal but to whose accuracy Ellington gleefully attested in an unpublished 1964 interview. The madam, he said, invited him to choose a female companion for the evening. At first he hesitated, but Mills and the dowager cheered him on, and in due course he changed his mind: “I was feeling my champagne . . . so finally I stood up and I waved to the madam and I says, ‘Madame? I’ll take the three on the end.’”

Ellington and his sidemen returned to New York on August 9, where they learned that they had been written up in

Time

on the same day that they opened at the Palladium. The story, entitled “Hot Ambassador,” was the first time that the weekly newsmagazine had mentioned the band other than in passing, and though it was written in

Time

’s condescending, self-parodic house style, it was still good news for Ellington and Mills:

Pianist Percy Grainger has likened the texture of Ellington’s music to that of British Composer Frederick Delius. Scholarly musicians are looking forward to a Duke Ellington review which is scheduled for New York next season. Such lofty recognition has injected no jarring, self-conscious note into Ellington’s performances. . . . Ellington’s arrangements, apparently tossed off in the approved hot, spontaneous manner, have been carefully worked out at rehearsals beginning often at 3 A.M. after his theatre and night-club engagements, which gross as much as $250,000 a year. Ellington will sit at the piano, play a theme over, try a dozen different variations. Spidery Freddy [sic] Jenkins may see an ideal spot for a hot double-quick trumpet solo. Big William Brand [sic] may be seized with a desire to slap his double-bass, almost steal the percussion away from Drummer Sonny Greer. Duke Ellington lets all his players have their say but listens particularly to the shrewd advice of pale Cuban [sic] Juan Tizol, his valve trombonist.

They also read “Introducing Duke Ellington,” an article published in the August issue of

Fortune

that described Ellington’s rise to fame in such a way as to leave no doubt of his musical achievements: “Ellington has never compromised with the public taste . . . He has played

hot

music, his own music, all the way along.” But it also stressed the profitability of Duke Ellington, Inc., making the band sound like nothing so much as a blue-chip stock: “Cleverly managed by Irving Mills, [Ellington] has grossed as much as $250,000 a year, and the band’s price for a week’s theatre engagement runs as high as $5,500. . . . The top salary in this group is $125 a week—approximately equal to the best symphonic wages.”

The combined effects of the tour and the burst of publicity that followed it put an end to Ellington’s funk. Even in the sober account that he wrote for

Music Is My Mistress

, he made clear how much it had meant to him to have his music taken seriously in Europe: “The atmosphere in Europe, the friendship, and the serious interest in our music shown by critics and musicians of all kinds put new spirit into us, and we sailed home . . . in a glow that was only partly due to cognac and champagne.” He had put it more emphatically after returning to America in 1933: “The main thing I got in Europe was

spirit,

it lifted me out of the groove. That kind of thing gives you courage to go on with a lot of things you want to do yourself. . . . If they think I’m

that

important, then maybe I have kinda said something, maybe our music does mean something.”

Part of what he meant by “that kind of thing” was that he now had an inkling of what it would be like to live in a land where the color of his skin mattered less than the size of his talent: “Europe is a very different world from this one. You can go anywhere and talk to anybody and do anything you like. . . . When you’ve eaten hot dogs all your life and you’re suddenly offered caviar it’s hard to believe it’s true.” Years later, on a return visit to England, Ellington was staying at a luxury hotel, standing on the veranda and chatting idly with a white acquaintance. “You know, I love this place,” he said. “I don’t know if you realize this, but I have the utmost difficulty staying in a hotel like this in the United States.” The knowledge that there were places in the world where he could check into such hotels without wondering whether his reservation would be honored buoyed him up for some time to come, and its effects on his music were immediate—and audible.

7

“THE WAY THE PRESIDENT TRAVELS”

On the Road, 1933–1936

E

LLINGTON AND HIS

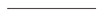

musicians paused in New York just long enough to cut four sides for Brunswick. Then they went back on the road, not to return until January. This time, though, they played for two months in Dallas, San Antonio, and Oklahoma City before heading north to Chicago. While the band had long been reluctant to tour the South—only a handful of black groups from the north had dared as yet to do so—it was received with enthusiasm everywhere. Moreover, the newspapers that covered the tour did so no less enthusiastically (though most of them refused as a matter of policy to print a photograph of a black man, opting instead to run respectful caricatures, one of them drawn by Al Hirschfeld, that were commissioned and distributed by the Mills office). The

Dallas News

went so far as to call Ellington “something of an African Stravinsky.” Prior to 1933 it had been unthinkable for Ellington to be described as a composer of significance other than in a black paper. Soon it would become a cliché.

Duke Ellington by Al Hirschfeld, c. 1931. Irving Mills commissioned the jazz-loving theatrical cartoonist to draw a sketch that could be published by newspapers whose editors were unwilling to run photos of a black person—even one who, like Ellington, was an international celebrity. This witty (and respectful) art-deco caricature was included in one of the advertising manuals sent out by Mills’s office

Ralph Ellison, who saw the band when it came to Oklahoma City in November, never forgot the impression that it made on him:

And then Ellington and the great orchestra came to town; came with their uniforms, their sophistication, their skills; their golden horns, their flights of controlled and disciplined fantasy . . . Where in the white community, in any white community, could there have been found images, examples such as these? Who were so worldly, who so elegant, who so mockingly creative? Who so skilled at their given trade and who treated the social limitations placed in their paths with greater disdain?

Ellington and his men had become a symbol of racial aspiration, one that cut across the dividing lines of region and class. In December

The

Pittsburgh Courier,

one of the country’s most influential black papers, ran a story about their appearance in Amarillo, proudly reporting that they had been “the talk of the city.” To the readers of the

Courier,

it was stop-press news that Ellington had been a hit with southern whites, just as it was news that he made big money at a time when no one else seemed to be making any money at all: “Carrying more than $30,000 worth of musical and uniform equipment and the startling earning power of over $5,500 weekly, the debonair Duke Ellington’s brilliant band . . . has earned the unique distinction of being the highest paid and most glamorous musical aggregation in all America.” Nowhere does money talk more eloquently than to poor but proud men and women who fight every day to put bread on their tables.

Having successfully dipped his toe into the muddy waters of the South, Ellington now jumped in headfirst. In July of 1934 the band performed in Atlanta. From there it went to Birmingham, Chattanooga, and Nashville. After that its trips below the Mason-Dixon Line became more frequent. Somewhere along the way, Ellington (or, more likely, Mills) learned how to insulate himself and his men from the hostile world around them by traveling not in a rented bus but on two private Pullman sleepers and a seventy-foot baggage car:

Everywhere we went in the South, we lived in them. On arrival in a city, the cars were parked on a convenient track, and connections made for water, steam, sanitation, and ice. This was our home away from home. . . . When we wanted taxis, there was no problem. We simply asked the station manager to send us six, seven, or however many we wanted. And when we were rolling, of course, we had dining-car and room service.