Duke (24 page)

Authors: Terry Teachout

The Crosby-Ellington “St. Louis Blues” pits the singer against Barney Bigard, Johnny Hodges, Tricky Sam Nanton, and Cootie Williams, all of whom are in scene-stealing form, though Crosby holds his own without breaking a sweat, nonchalantly scatting his way through a climactic up-tempo chorus. But the flip side, a four-minute instrumental remake of “Creole Love Call,” is at least as interesting, for it gives us one of our first glimpses of Ellington’s penchant for revisiting and transforming the works of his youth. While he had recorded multiple versions of many of his best-known numbers, the remakes were usually closely similar to the originals. The 1932 “Creole Love Call,” by contrast, is a slowed-down version in which Adelaide Hall’s wordless vocal is played on trumpet by Arthur Whetsel and the orchestral part is enriched with new countermelodies and glints of dissonance. Is it an improvement on the 1927 version? That is beside the point: Ellington’s purpose was not to replace the original but to offer a different perspective on it. As Russell Procope, who joined the band in 1946, said of his later versions of “Mood Indigo,” “A new arrangement would freshen it up, like you pour water on a flower, to keep it blooming.”

The French jazz critic Hugues Panassié, who devoted an entire chapter to Ellington in

Le jazz hot,

his pioneering study of American jazz, heard several of these alternate versions for the first time when the band played in Paris in 1933. He found it fascinating that Ellington saw no need to prepare definitive texts of his compositions, preferring to leave them (in Clark Terry’s phrase) in a state of becoming:

What struck me strongly was the discovery that the arrangements themselves sometimes differed from those used on the records. I understood that some had been done over, improved, enriched over the years by new ideas that came to Duke or his men. For others, I realized with astonishment at the second concert, several quite different arrangements existed which Duke used alternatively—sometimes one, sometimes another. Thus the “Mood Indigo” of the first concert scarcely resembled that of the second.

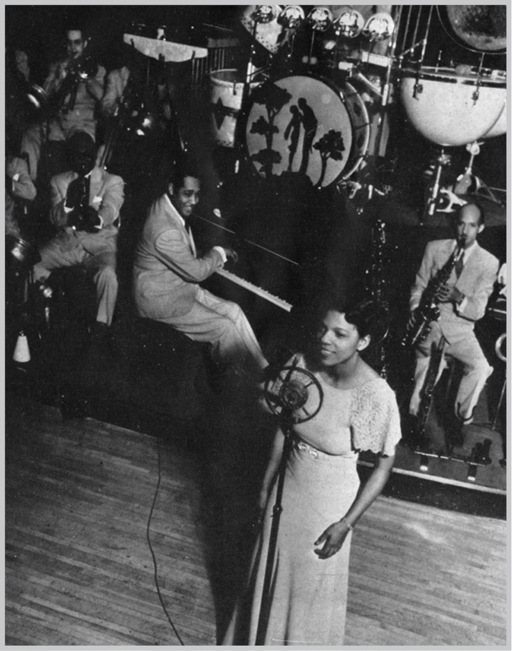

Another way in which Ellington enriched his music was to add musicians to the band. A year earlier he had hired his first full-time vocalist, Ivie Anderson, who had been singing with Earl Hines’s band in Chicago. Anderson had a low, pointed voice with crystalline diction and a cutting nasal edge. Her first records were too obviously influenced by the stagey style of Ethel Waters, but she soon loosened up and proved to have an infallible sense of swing. Though not conventionally attractive, Anderson had abundant sex appeal, and Ellington enhanced her gamine appearance by instructing her to dress only in white onstage, which set off her dark brown skin. He also gave her another piece of advice: “When I joined his band I was just an ordinary singer of popular songs. Duke suggested I find a ‘character’ and maintain it.” The character she assumed, that of a tough yet vulnerable woman who viewed the world with knowing irony, seems not to have been all that different from what she was like in private life. While a surviving radio interview reveals Anderson to have been cultivated and soft-spoken, she was also a card shark who could outplay anyone in the band but Ellington himself, and her toughness, Rex Stewart said, was no pose: “Off stage our Miss Anderson was another person entirely, bossing the poker game, cussing out Ellington, playing practical jokes or giving some girl-advice about love and life.” Asthma finally forced her out of the band in 1942, but by then her classic performances of “I Got It Bad (And That Ain’t Good),” “Rocks in My Bed,” and the anthemic “It Don’t Mean a Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing),” Anderson’s 1932 recording debut, had secured her reputation as the best singer ever to work with Duke Ellington.

Tough yet vulnerable: Ivie Anderson at the London Palladium in 1933. The band’s first female vocalist, Anderson was prominently featured at Duke Ellington’s European debut. Her tart, ironic singing meshed perfectly with his urbane musical style, and after she left the band in 1942, he never found another singer who suited him so well

A few weeks after recording with Crosby, Ellington made an even more consequential hire, that of the trombonist Lawrence Brown, whom Irving Mills had heard playing in the house band at Frank Sebastian’s Cotton Club in Los Angeles, which shared its name with the Harlem nightspot. Born in 1907, Brown was a thoroughly schooled musician from Kansas who had moved to California as a child. The son of an African Methodist Episcopal minister, he was a nonsmoking teetotaler who was promptly and permanently dubbed “Deacon” by his new bandmates. Though he loathed the nickname, he earned it many times over: Ellington described his demeanor as “very staid, a little stuffy, really,” and no one made him stuffier than Ellington himself. From the outset, the two men found it inordinately difficult to get along. “I never knew you, I never met you, I never heard you,” Ellington told Brown at their first meeting. “But Irving says get you, so that’s that.” The exchange set the tone for a four-decade relationship so contentious that they stopped speaking to one another save at rehearsals, ultimately parting company not with frigid civility but in a shocking burst of violence.

It was understandable that Brown should have disliked Ellington. Not only did the trombonist believe that his new boss had stolen “Sophisticated Lady” from him, but he undoubtedly feared that Ellington would also steal back Fredi Washington, whom he married a year after joining the band. He may well have been right to be afraid. Jean Bach, who knew both Ellington and Washington, later claimed that the bandleader arranged the marriage in order to cover up his continuing romance with the actress: “Duke decided and they plotted. He said, ‘There’s this young guy coming in from California. He’s obviously not married. So you two should get married. And there would be a reason to travel with the band.’ Lawrence didn’t know what hit him. He just thought this gorgeous woman wants to get married.” True or not, he came to regard Ellington not merely with distaste but with a contempt that flowered into full-blown hatred. At the end of his life, Brown dismissed him as “an exploiter of men and a seducer of women,” a judgment as summary as a slap in the face. For his part, Ellington spoke distantly of Brown in

Music Is My Mistress,

summing up his playing with a left-handed compliment: “As a soloist, his taste is impeccable, but his greatest role is that of an accompanist.”

In fact, he was one of the orchestra’s most identifiable solo voices, a masterly technician with a chocolate-smooth, cellolike tone whose section mates marveled at his skill. “I sat next to him in the Ellington band for five years and never heard him make one mistake,” said Claude Jones. “I can’t say that for any other trombonist I know.” Brown’s style bore no resemblance to the raucous playing of most jazz trombonists of his generation: “It was my own idea. Why can’t you play the melody on the trombone just as sweet as on the cello? I wanted a big, broad tone, not the raspy tone of tailgate. . . . To get the smoothness I wanted, I tried to round the tone too much, instead of keeping it thin. Mine, to my regret, has become too smooth.” The self-doubt revealed in that remark encompassed his solo work: “I can’t play jazz like the other guys in the band. All the others can improvise good solos without a second thought. I’m not a good improviser.” It was true that Brown, like many other jazzmen of the thirties and forties, preferred to map out his solos in advance instead of spinning them off the top of his head, but he was also capable of playing with swaggering abandon, as he does in the devil-take-the-hindmost interlude with which he caps Ellington’s 1942 recording of “Main Stem,” and except for the nonpareil Tommy Dorsey, no trombone player was better at caressing a tune.

Though Ellington rushed to feature Brown in numbers like “The Sheik of Araby” that highlighted his sure-footed virtuosity, it was the trombonist’s lyricism to which he responded most strongly, and “Sophisticated Lady” was the first of the many ballads, including “Solitude” and “In a Sentimental Mood,” with whose worldly air the two men (and, later, Johnny Hodges) would long be identified. The band would play “Sophisticated Lady” thousands of times in dozens of different versions, and it evolved at last into a feature for Harry Carney, who invested the melody with a dark-brown richness all his own. The 1933 recording, by contrast, has a brisk, even youthful air, and it opens not with Carney but with Brown, who plays his own tune warmly and sensitively, first “straight,” then with graceful ornamentation. The performance, which also contains an elaborate saxophone-section variation on the theme, ends with eight fluttery bars from Hardwick that have a near-Victorian air.

Ellington had worked this vein before, and to him it was as “black” as the blues, but there would always be a small clique of critics who thought otherwise, treating Brown as an alien presence who put his authenticity at risk. The first of them was Spike Hughes, formerly one of Ellington’s most unswerving advocates:

The one person, to my mind, who is definitely out of place [in the band] is Lawrence Brown. This artist is a grand player of the trombone, and would be a tremendous asset to any other band on account of his original style, but his solo work is altogether too “smart,” or “sophisticated,” if you will, to be anything but out of place in Duke’s essentially direct and simple music.

John Hammond, who liked nothing more than to offer unsolicited advice to musicians and nothing less than to have it ignored, agreed with Hughes, calling Brown a “brilliant musician [who] is out of place in Duke’s band. He is a soloist who doesn’t respect the rudiments of orchestral playing. Constantly he pushes himself to the foreground. In any other orchestra no objection would be raised; but Duke’s group is very properly the voice of one man, and that gent is not Mr. Brown.”

Eight decades later, the lofty condescension of these reviews still grates. You can almost see Hammond and Hughes patting their precocious charge on the head, warning him not to get too big for his britches. For the moment he kept his mouth shut, but he knew what they were writing about him and found it galling, though he also knew that his listeners disagreed. Ellington’s “sophisticated” ballads would always rank among the band’s most popular numbers, and a time would come when he felt secure enough to strike back in print at the meddlers who prided themselves on knowing what was best for him. As for the notion that Brown was too much the soloist to fit into Ellington’s trombone section, one can only laugh at its absurdity, since there has never been a less well-matched trio. No one in his right mind would have dreamed of asking three musicians as dissimilar in sound and style to play ensemble passages together—no one, that is, but Duke Ellington, who gloried in their incongruity. “Your poppa likes to hear the trombones play loud,” Tizol told Mercer Ellington, and he never missed an opportunity to turn them loose and let them tear up the joint.

• • •

Brown was later to claim that even after Ellington hired him, he did not allow the trombonist to play with the band until he added another musician to the roster. The problem, Brown said, was that he would otherwise have been the thirteenth man on the bandstand, an anomaly that the triskaidekaphobic composer allegedly refused to tolerate. This sounds too good to be true, especially since Ellington had decided that thirteen was his lucky number after opening a successful engagement at Chicago’s Oriental Theatre on February 13, 1931 (a Friday, no less). But Brown did not cut his first record with the band until May 16, 1932, the same day that Otto Hardwick, Ellington’s wandering prodigal, returned once more to the studio, suggesting that there may be something to the story.

Either way it is a matter of amply attested record that Ellington was superstitious to a fault, and a catalogue raisonné of his phobias would fill a closely packed page or two. He hated the color green because it reminded him of grass: “When I was eight, I decided that grass was unnatural. It always makes me feel sort of creepy. It reminds me of graves.” He hated brown even more because he happened to be wearing a brown suit on the day his mother died. “Once someone gave him a sweater flecked with brown,” Don George recalled. “He turned away, saying, ‘It isn’t blue.’” It was his lifelong habit to throw away any garment with a loose button, and Mercer Ellington said that he would not buy socks or shoes for anyone because he was convinced that it would cause them to “walk away from him.” He feared sea travel, air travel, drafts, yellow manuscript paper, people who whistled or ate peanuts backstage . . . the list goes on and on.

Many of his superstitions centered on death, of which he was so afraid that it was said that he would walk out of a room whenever the subject was broached, and most of them were both irrational and unproductive. But the day that Brown and Hardwick joined the band was lucky by any stretch of the imagination. For the next eight years, the instrumentation of the Ellington band (save for the number of bass players, which fluctuated between one and two) remained constant, as did nearly all of the faces on the bandstand. After endless trial and error, he had found the lineup that he wanted—three trumpets, three trombones, four saxophones, and four rhythm-section players—and he had also found the men he wanted, all of whom played their instruments in ways so personal that each one was instantly identifiable. Having created the conditions necessary for the proper functioning of the Ellington Effect, he now reaped its rewards. One by one, week by week, the scores piled up, and what had once been a band book now became an oeuvre.