Duke (37 page)

Authors: Terry Teachout

Duke asked Marable if he could sit in—they knew one another well. Duke and Blanton began playing together and still hadn’t exchanged a word. Duke kept changing key and Blanton was on to every move. The tune ended and Marable called out “How do you like my bass player?” Duke coyly said, “I was just going to ask you the same question.” Then he laughed and said, “He’s my bass player now.”

Duke already had a bass player but he added Jimmie Blanton to the band, bought him a white suit, and next night stood him out front of the band and featured him.

Word of the encounter spread quickly. “We wonder if the maestro is planning to add Jimmie Blanton, bass fiddler with Fate Marable’s band, to his aggregation,” a columnist for

The

St. Louis

Argus,

a black newspaper, reported a week later. Ellington never forgot his late-night visit to Club 49: “I flipped like everybody else . . . we didn’t care about his [lack of] experience. All we wanted was that sound, that beat, and those precision notes in the right places, so that we could float out on the great and adventurous sea of expectancy with his pulse and foundation behind us.” Blanton left St. Louis with the band on November 3, and Ellington started featuring him at once. Within weeks jazz-savvy journalists were taking note. An Indianapolis columnist who heard Blanton play “Sophisticated Lady” with Ellington told his readers that “it was really unique and fascinating and spine-chilling.” Less than three years later, he was dead.

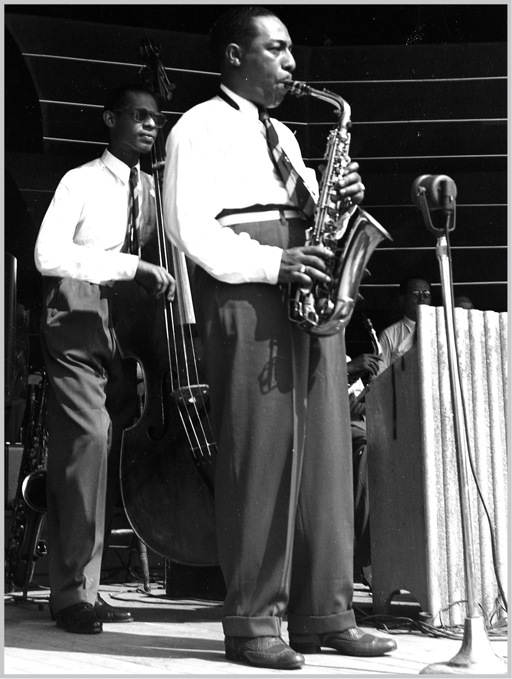

“All we wanted was that sound”: Jimmie Blanton and Johnny Hodges, Detroit, 1940. The outstanding jazz bassist of the forties accompanies the Ellington band’s most celebrated soloist. Blanton’s hard-swinging, technically advanced playing spurred his colleagues, Hodges included, to new heights of virtuosity

Because he died so young and appears never to have been interviewed, we know little about Blanton’s life beyond the barest of details. He was born in Chattanooga in 1918. Gertrude, his mother, was a professional musician who gave him piano lessons as a child, and he is also said to have played violin and alto saxophone in a family band before switching to bass around the time that he went to Tennessee State University to study music. It’s not known whether Blanton studied the instrument there, but he later made use of playing techniques with which few jazz bassists were then conversant, indicating that he took lessons from a classically trained teacher prior to meeting Ellington. Barney Bigard said that he was studying with an unnamed “professor” in 1939: “When he left St. Louis to join us his professor gave him a list of all the symphony bassists in the towns around the country and a letter of introduction to them. . . . Jimmy [

sic

] would go look them up and take his lesson.” (The “professor” in question appears to have been Karl Auer, the longtime principal bassist of the St. Louis Symphony.) Blanton started playing with Marable during his summers at TSU, then joined the Jeter-Pillars Orchestra, a St. Louis–based territory band with which he is believed to have cut his first records in 1937. He appears to have been working regularly with Marable when he met Ellington.

While Blanton was not the first classically trained jazz bassist, he was the first one to develop into an improvising soloist of the top rank. “Listen, you’re going to hear something you never heard before—a bass player who plays melody, and in tune,” Ellington told Leonard Feather in 1941. Blanton was all that and much more. His focused sound was slender but penetrating, his pizzicato playing awesomely fleet, his sense of swing unerring. “He shocked us all . . . he had those tremendously long fingers and he really knew his positions,” Milt Hinton said. Best known for his unprecedented ability to play hornlike solos in the upper register of his instrument, Blanton was one of the few jazz bassists of his generation who, like Slam Stewart, was also adept with the bow. Not only did his playing stun jazz musicians and buffs, but it caught the ear of classical musicians who had never heard a bass plucked with such fluency. Rex Stewart claimed that Igor Stravinsky “spent [an] entire evening enjoying Blanton” at a New York club. “Despite his youth, there was a certain calm assurance which vibrated visibly, and you could sense this permeating his public and private life,” he added. “When he spoke, which was rarely, people listened, feeling, truthfully, that he was wise beyond his years.” Photographs show that he was boyishly handsome, and it amused Ellington’s sidemen that he preferred making music to carrying on with the girls who pursued him. “They’d find out the hotel he was staying in and they would call his room,” Bigard said. “He’d answer and say, ‘Yes. Just a minute. I’ve just got to finish what I was doing.’ Don’t you know he would just leave that receiver down and forget that they were on the line. Just go right back to that bass and start in with his practicing again.”

They also worried about his health, for the physically fragile Blanton was thought to be taking his life in his hands by frequenting late-night jam sessions with compulsive regularity. “What really struck me when I finally saw him was how slight and frail a young man he was,” said George Duvivier. “It kind of frightened me because I knew all about the Ellington orchestra: how they lived and traveled and their after-hours escapades. The thought occurred to me, ‘My Lord, this guy just might not make it!’” None of his new compatriots seems to have been surprised when Blanton was diagnosed with tuberculosis (a disease that in the thirties and forties was vastly more common among blacks than whites) two years later. The speed with which it laid him low suggests that he was already ill at the end of 1939, and that he might even have known that his time was short.

Ellington rushed Blanton into a recording studio as soon as he could. On November 22, three weeks after he joined the band, the two men cut a pair of duets in Chicago. “Blues” and “Plucked Again,” the first bass-and-piano jazz duets ever to be commercially recorded, are top-of-the-head improvisations remembered today only because they allow us to hear Blanton’s playing up close for the first time. A year later he and Ellington recorded four more carefully prepared sides, the best of which is “Pitter Panther Patter,” that show off his pizzicato work to much better effect (while also showing that his bowed intonation was iffy). By that time Blanton had been featured on two full-band recordings, “Jack the Bear” and “Sepia Panorama,” though his springy ensemble playing is audible on every side that he recorded with Ellington. “He wouldn’t interfere with your solo—playing riffs behind your riffs—he would play a good, solid beat for you,” Bigard said. Blanton’s virtuosity stunned his less facile section mate. In January of 1940 the Ellington band arrived in Boston, and Billy Taylor quit the band there. “Right in the middle of a set, [he] packed up his bass and said, ‘I’m not going to stand up here next to that young boy playing all that bass and be embarrassed,’” Ellington wrote in

Music Is My Mistress

. “He left the stand . . . and went on out the front door. I think it takes a big, big man to acknowledge the facts and take low.”

It was in Boston that Ellington made an equally consequential addition to the band. A columnist for the

New York Amsterdam News

reported in January, “Ben Webster denies plans to switch from Teddy Wilson to Duke Ellington, but the grapevine has him making the change.” (In those far-off days the hiring of a new musician by a top bandleader was thought worthy of note by the entertainment columnists of black newspapers.) Once more the rumor was true, and Ellington’s sidemen, who liked to affect a blasé pose, rejoiced at the arrival of a saxophonist who was, after Johnny Hodges and Sidney Bechet, the greatest soloist ever to pass through their ranks.

Born in 1909 in Kansas City, Benjamin Francis Webster was the son of a violent drunk who quit the scene shortly before his birth. His mother and great-aunt, both of them churchgoers, endeavored to raise him in the paths of righteousness. “My mother, she wanted me to be a little Lord Fauntleroy, with that big Buster Brown collar, and take violin lessons,” Webster recalled. He had other ideas. Having inherited his father’s temper, the boy smashed his violin to bits at the age of twelve, taught himself how to play stride piano, and started haunting the nightclubs of the ghetto on whose fringes he lived, where he discovered the pleasures of hard drinking and loose women. Webster spent two years at Wilberforce University in Ohio, the oldest private black college in America, but all he cared about was music, and when he heard Fletcher Henderson’s band, his fate was sealed. An adequate but undistinguished pianist, he took up the alto saxophone in 1928. A year later he was playing alongside Lester Young in the reed section of Young’s father’s band. Soon afterward he switched to tenor and started working his way up through the ranks of the best black bands. Henderson, Bennie Moten, Cab Calloway, and Teddy Wilson were all impressed enough by his still-unfinished playing to hire him, though his personality gave some of them second thoughts.

Apprehensive friends soon nicknamed Webster “the Brute,” and Rex Stewart, who called him “the hoodlum swingster,” seems to have been the first person to compare him to Dr. Jekyll, whose rampaging alter ego, the sadistic Mr. Hyde, terrorized the citizens of London. Alcohol was the potion that unleashed his demons. Webster was, in the words of his friend Jimmy Rowles, “kind of an introvert, always respectful when he was sober.” But drinking disabled his inhibitions and made him as violent as his father had been. He never allowed the Lord’s name to be taken in vain in his presence, and when anyone broke his rule in a bar, he beat them up. Predictably enough, he treated his lovers like whores. To the saxophonist Garvin Bushell, he was “an unusual character, very humorous, also very tough. He didn’t get along with the girls at all because he’d knock them down if they said the wrong thing to him. . . . I think Ben was influenced by the hustlers and pimps—he had their mannerisms.”

It was Webster’s dream to work with Duke Ellington. “Every time I’d run across some of Duke’s men I would ask for a job,” he said. In August of 1935 he got his chance, if only for a brief time: “Barney Bigard took a little vacation . . . and I joined Duke when the opportunity popped up.” He can be heard playing a thrusting solo on the band’s recording of “Truckin’,” a song written by Rube Bloom and Ted Koehler for a Cotton Club show, in which Ivie Anderson celebrates a Harlem dance craze. At a time when other Swing Era bands featured tenor-sax solos, none of Ellington’s men specialized in the instrument. From then on, he said, “I always had a yen for Ben.” But he would not poach a member of a band in which he had a financial interest, and Webster was playing with Cab Calloway at the time, so the flirtation went no further—for the moment.

After Ellington broke with Irving Mills and traded his interest in the Calloway band back to his ex-manager, such niceties became irrelevant. In January of 1940 Webster joined the band of his dreams, and gave as good as he got. Playing Ellington’s big-band charts alongside Johnny Hodges, a longtime idol, knocked the rough edges off Webster, whose mature style combined lyricism with pile-driving swing. He described it as “a kind of alto approach to the tenor,” influenced by Hodges and Benny Carter, but it was also a manifestation of his own split personality. For a time he had been obsessed with Coleman Hawkins, but when a friend suggested that emulation had become imitation, Webster changed his ways, retaining the older man’s voluminous tone while embracing Lester Young’s tunefulness, punctuating his solos with pungent growls that were all his own.

Off the bandstand Webster was warm, generous, and a good comrade—when sober. He became close to and protective of Jimmie Blanton, who nicknamed him “Frog.” Rex Stewart was touched by his solicitousness: “Ben was a different man as he watched over Blanton like a mother hen . . . he cut way down on his whiskey and would sit by the hour counseling young Jimmy [

sic

] on the facts of life.” One night he carried Blanton home on his back through a blizzard, the young man’s bass tucked under the saxophonist’s arm. The closeness of their mutual understanding can be heard in a version of “Star Dust” recorded at a dance in 1940, in which Webster all but whispers Hoagy Carmichael’s melody as Blanton accompanies him with self-effacing simplicity.

• • •

A month after he joined the band, Webster played alongside Blanton on Ellington’s final sessions for Columbia, which took place in Chicago. Columbia seized the opportunity to cut sensitively sung vocal versions of “Mood Indigo” and “Solitude” by Ivie Anderson, plus Anderson’s only commercial recording of “Stormy Weather,” which she had sung onstage with the band ever since Ethel Waters premiered the song at the Cotton Club in 1933, and a pleasant but uneventful instrumental remake of “Sophisticated Lady.” Webster is heard throughout the date, proclaiming his arrival with relaxed authority. When it was over, Ellington signed a contract with Victor and hit the road to play a string of stage shows in Michigan and Indiana. The next time he set foot in a studio, he would cast off from the past and set eager sail on the sea of expectancy.