Duke (40 page)

Authors: Terry Teachout

11

“A MESSAGE FOR THE WORLD”

Jump for Joy, 1941–1942

I

ALWAYS CONSIDER my

problems opportunities to do something,” Duke Ellington told Ralph Gleason. “Like Jimmy Valentine or Houdini.” At the beginning of 1941, a few weeks after Cootie Williams left the band, Ellington was confronted with another “opportunity,” this one of an unusually nerve-racking kind. The American Society of Composers and Publishers, America’s largest musical performing-rights organization, was determined to extract more money from the radio networks for the privilege of airing songs written by its members, on whose behalf ASCAP collected and distributed performing-rights fees. The networks responded by setting up a competing organization called Broadcast Music Incorporated (BMI). At BMI’s behest, the networks stopped airing ASCAP-registered songs. That amounted to some 1,250,000 songs, including nearly all of the top hits of 1940. The boycott went into effect on January 1, forcing bands that performed on the radio to play either BMI-controlled or public-domain songs during their programs. Soon every bandleader was frantically commissioning arrangements of nineteenth-century ballads (the most frequently aired of which was Stephen Foster’s “Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair”) and unknown tunes by BMI songwriters.

Two days after the boycott went into effect, Ellington and his men began a seven-week stand at the Casa Mañana, a popular nightclub not far from the MGM studios that had a broadcast wire, and its leader was caught flat-footed. From the time that Irving Mills took over the management of the band in 1927, it had specialized in the music of Duke Ellington—and he had been a member of ASCAP since 1935. That was where Billy Strayhorn came in. “When we opened . . . we had air time every night, but could not play our library,” he recalled. “We had to play non-ASCAP material. Duke was in ASCAP, but I wasn’t. So we had to write a new library.” Strayhorn, however, was still finding his footing: Ellington had only recorded three of his full-band arrangements in 1940, and none was of an original composition. Though his versions of “Chloë,” a twenties ballad that he had adapted from a stock arrangement, and “Flamingo,” a brand-new pop tune sung by Herb Jeffries, were dazzling, they were mere drops in an empty bucket that had to be filled as quickly as possible.

Ellington thereupon proceeded to pull a rabbit out of his hat, advising the press that his son would be joining the band. “After spending $8,000 for a musical education for my son I will now have a chance to realize the returns,” he said. “Mercer will sit at my right hand during 1941 and write compositions under his own name. He’ll do much arranging as well as composing.” It sounded believable enough, and it was true that Mercer, a classically trained musician who had studied at the Juilliard School with William Vacchiano, the longtime principal trumpeter of the New York Philharmonic, aspired to write for his father’s band. Nor did he need to be told twice what had fallen into his and Strayhorn’s laps: “Overnight, literally, we got a chance to write a whole new book for the band. It could have taken us twenty years to get the old man to make room for that much of our music, but all of a sudden we had this freak opportunity. He needed us to write music, and it had to be in our names.” But Mercer was even less seasoned than Strayhorn. He had written as yet only one piece of music that the old man had been willing to record, a formulaic school-of-Ellington instrumental called “Pigeons and Peppers” that was cut by a Cootie Williams–led small group in 1937, seven months after Mercer’s eighteenth birthday. Nevertheless, Ellington had no choice but to rely on his son and his protégé, who holed up together in a hotel room, chugged blackberry wine and chain-smoked, and turned out charts as fast as they could.

A month after the ASCAP boycott went into effect, Ellington took the band into a Hollywood studio and recorded five new compositions by Strayhorn and Mercer. The first one was a brisk, engagingly tuneful swing number that Strayhorn had previously scrapped, believing that it sounded too much like one of Fletcher Henderson’s charts to pass muster. Mercer thought otherwise, and “Take the ‘A’ Train” went straight into the book, together with a puckish riff tune called “John Hardy’s Wife” and “After All,” a ballad whose melody was intoned by Lawrence Brown’s trombone. Mercer’s contributions were “Blue Serge,” a midnight-black orchestral study to which Ben Webster contributed one of his most impassioned solos, and “Jumpin’ Punkins,” a carefree medium-tempo feature for Sonny Greer that bore Duke’s stamp on every page. Later that year the band cut Mercer’s “Moon Mist,” a slowly swaying, pastel-colored ballad in which Ray Nance’s sweet-toned violin playing was heard to sumptuous effect.

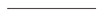

“Every note of music, every lyric, meant something”: A souvenir program for

Jump for Joy,

Ellington’s first stage musical, which opened in Los Angeles in 1941. The all-black, socially conscious revue delighted West Coast audiences but never made it to Broadway

It was no coincidence that all of the pieces that Mercer produced during this time sounded as though his father had composed them, for they were written under Ellington’s close supervision: “He’d set problems for me, scratch out what he thought was in poor taste, and preset harmonies for me to write melodies against.” Strayhorn, by contrast, needed no hand-holding from Ellington, who promptly made “Take the ‘A’ Train” the band’s new theme song. Over the next few months he continued to write and arrange pieces that were recorded as soon as the copyist’s ink was dry. Among other things, Hodges cut combo versions of “Day Dream” and “Passion Flower,” Barney Bigard recorded a similar tune called “Noir Blue,” and the full band weighed in with “Chelsea Bridge,” a Ravel-influenced nocturne inspired, Strayhorn said, by James McNeill Whistler’s

Nocturne: Blue and Gold—Old Battersea Bridge

. By the time that ASCAP agreed to cut its fees, bringing the boycott to an end, Strayhorn was solidly established as a composer of consequence. Even after Ellington’s own music returned to the airwaves, “Take the ‘A’ Train” remained his theme song, and the band would play it at least once a night for the rest of his life.

• • •

While Ellington’s two “yearlings,” as he liked to call them, were courting writer’s cramp by creating a new book of arrangements for him to play on the air, he was otherwise occupied. In February he took to the pulpit of Los Angeles’s Scott Methodist Church to deliver a secular sermon in honor of the local black community’s annual Lincoln Day services. The title of his remarks was “We, Too, Sing ‘America,’” an allusion to Langston Hughes’s poem “I, Too, Sing America,” and what he had to say was both proud and eloquent:

I contend that the Negro is the creative voice of America, is creative America, and it was a happy day in America when the first unhappy slave was landed on its shores. . . . We—this kicking, yelling, touchy, sensitive, scrupulously demanding minority—are the personification of the ideal begun by the Pilgrims almost 350 years ago.

Five months later he put that pride onstage when

Jump for Joy: A Sun-Tanned Revu-sical,

his first full-length stage show, opened at the Mayan Theatre in Los Angeles. Ellington had often spoken of his longing to write a Broadway musical, and though he had composed the music for two Cotton Club revues,

Jump for Joy

was a show of a different color, an all-black revue whose goal, he said, was “to give an American audience entertainment without compromising the dignity of the Negro people. . . . The American audience has been taught to expect a Negro on the stage to clown and ‘Uncle Tom,’ that is, to enact the role of a servile, yet lovable, inferior.” He had spent too many nights playing for rich whites at the Cotton Club to settle for less, but in 1941 it was daring for a black man even to consider such an undertaking, and it stands to reason that

Jump for Joy

should have been the brainchild of an unusual cast of characters.

The sparkplug for the show was Sid Kuller, a second-string Hollywood gagman and part-time lyricist who had written special material for movies by the Ritz Brothers and was currently at work on

The Big Store,

a Marx Brothers film. A jazz buff, Kuller heard Ellington at the Casa Mañana and invited him to hold weekend jam sessions at his house in Hollywood. One night the writer came home late from the studio. “Hey, this joint sure is jumpin’!” he said. “Jumpin’ for joy,” Ellington replied. Kuller then suggested that they should collaborate on a stage revue called

Jump for Joy,

and raised twenty thousand dollars on the spot from the Hollywood personages who were present. “Count me in,” said John Garfield, a stage actor who in 1941 was turning himself into a well-paid silver-screen tough guy. In due course he became one of the principal investors in and de facto producers of

Jump for Joy

.

It is a lovely tale, one that Kuller would repeat to interviewers for the next half century. But the backstory of

Jump for Joy

was more complicated than he let on. Years later he casually referred to the show’s backers as “the leftist Hollywood crowd.” He spoke more truly than most jazz historians know. In addition to writing jokes by the bushel, he had worked on

Meet the People,

a revue that had run for 160 performances on Broadway in 1940.

Meet the People

was cut from the same political cloth as Marc Blitzstein’s

The Cradle Will Rock

and Harold Rome’s

Pins and Needles,

the most successful of the many left-wing musical revues and straight plays that grew out of the WPA’s Federal Theatre Project.

‡‡‡‡‡‡‡

Both shows figure prominently in the history of the Popular Front, the “anti-fascist” alliance through which agents of the Soviet Union sought to infiltrate and co-opt liberal groups in America and Europe in order (among other things) to manipulate public opinion by fostering the emergence of a “progressive,” Communist-friendly middlebrow culture. To speak of American culture in the thirties and forties is in large part to speak of the Popular Front and its adherents, both witting and unwitting. The plays of Lillian Hellman and Clifford Odets, the novels of John Steinbeck, the Western-themed ballet scores of Aaron Copland, the prolabor shows of Blitzstein and Rome: All were in their varying ways exercises in Popular Front–style cultural populism, and the makers of

Jump for Joy

meant to follow in their footsteps.

The success of

Pins and Needles

on Broadway inspired a group of Hollywood-based writers, among them Dashiell Hammett, Lillian Hellman, Langston Hughes, and Ira Gershwin, to launch the Hollywood Theatre Alliance, whose purpose was to mount similar shows in Los Angeles. The HTA first tried to produce a “Negro Revue” whose book would be cowritten by Hughes and Donald Ogden Stewart, author of the screenplay for

The Philadelphia Story

. When that venture fell through, Kuller approached Ellington, who was involved in preliminary discussions with the group, about writing a similar show. Ellington and the HTA then joined forces to start another group called the American Revue Theatre, under whose auspices

Jump for Joy

was produced. It was no secret that the HTA, like other such organizations in Los Angeles and New York, was full of Communists—including Hammett, Hellman, and Stewart—and the House Un-American Activities Committee would later describe it as a “Communist-front organization.” True or not, many of the members of “the leftist Hollywood crowd” who were involved in the creation of

Jump for Joy

were card-carrying Communists and fellow travelers (like John Garfield) whose goal was to advance the agenda of the Popular Front by creating a black counterpart of

Pins and Needles

.