Duke (49 page)

Authors: Terry Teachout

It is Sunday morning. We are strolling from 110th Street up Seventh Avenue, heading north through the Spanish and West Indian neighborhood toward the 125th Street business area. Everybody is nicely dressed, and on their way to or from church. Everybody is in a friendly mood. Greetings are polite and pleasant, and on the opposite side of the street, standing under a street lamp, is a real hip chick. She, too, is in a friendly mood. You may hear a parade go by, or a funeral, or you may recognize the passage of those who are making our Civil Rights demands.

You may indeed hear all these things, though not necessarily in that order, for

Harlem

is not a conventional piece of first-this-happens-then-that program music. If you listen

very

closely, though, you might also hear a not-too-distant echo of the equally fanciful program concocted by Deems Taylor for the 1928 premiere of George Gershwin’s

An American in Paris,

the tone poem after which

A Tone Parallel to Harlem

was almost certainly modeled. While Ellington is not known to have acknowledged any resemblance between the two pieces, he was definitely familiar with

An American in Paris,

which Gershwin had interpolated into

Show Girl

two decades earlier as the score for a production number.

Harlem

is organized in the same manner, all the way from the introductory “strolling” music to the hymnlike major-key theme that Ellington states midway through

Harlem

and weaves throughout the rest of the work, just as

An American in Paris

pivots on the jazzy trumpet theme that will later supply the musical material for its climactic peroration. The main differences between the two pieces are that

Harlem

is jazz, not jazzy, while Gershwin’s thematic material, unlike most of Ellington’s, is straightforwardly melodic—which is why

Harlem,

musically rewarding though it is, holds together less well than

An American in Paris,

on whose tuneful themes the average listener has no trouble hanging his hat.

Who arranged the full-orchestra version of

Harlem

? By his own admission, Ellington had no wish to learn how to write for a string section. “What on earth would I want with strings?” he told Leonard Feather at the time of the Metropolitan Opera House premiere. “What can anybody do with strings that hasn’t been done wonderfully for hundreds of years? It wouldn’t be any novelty, anyway: Paul Whiteman used strings 30 years ago. No, we always want to play Ellington music—that’s an accepted thing in itself.”

¶¶¶¶¶¶¶¶

So he left the job to Luther Henderson, who knew quite well why Ellington wanted to hear his music performed by symphony orchestras: “He wanted me to legitimize him in this society we call classical music.” Henderson’s choice of words was perceptive. If Ellington had been seriously interested in the orchestra as a musical medium, he would have learned how to write for it himself. What he really wanted was the “legitimacy” that came from having his works performed by symphony orchestras, and he could get that without learning how to write for strings. It was because he never bothered to do so that his later “symphonic” works, interesting though some of them are, lack the defining touches of orchestral color that could only have been supplied by the man himself.

The critics mostly thought well of

Harlem,

less so of the band that played it. “Something important and vital is missing . . . at no point did the band or the evening really catch fire,” Mike Levin wrote, adding that “the Ellington rhythm didn’t seem to be booting the men as it should have.” That Greer was falling apart was obvious to everyone, including Ellington, who hired a second drummer, Bill Clark, to cover up for his inadequacies. Greer’s colleagues had long been troubled by the inconsistency of his playing. “Cootie [Williams] and I always sat near the drums and, whenever Greer wasn’t putting the beat down hard enough, we would both whip his flagging rhythm until it moved and swung,” Rex Stewart said. Even so, the subtlety with which he responded to the band’s playing had always kept Ellington content—but no longer.

Down Beat

reported in February that “Greer’s 30-year association with Duke might very soon be at an end.”

Ellington hated to fire anyone, and it’s hard to imagine him dropping the blade on the band’s last surviving charter member. Norman Granz relieved him of the responsibility, doing so in the most jaw-droppingly sensational way imaginable. Shortly after the premiere of

Harlem,

the hard-nosed promoter, whose Jazz at the Philharmonic concert tours had made him rich, announced that Johnny Hodges was leaving the Ellington band to start a Granz-managed combo of his own—and that Greer and Lawrence Brown were going with him.

Granz had tried without success to make Duke Ellington, Inc. a wholly owned subsidiary of JATP. His proposal to Ellington sounded plausible enough on paper: “Why don’t you give up the band and I’ll pay you a weekly salary . . . and any time we get ready to tour, well, then, you can hire the cats and you can pay them more and be sure to get them, then the rest of the time they’ll find other gigs to do. And you can devote your time to writing.” But he failed to grasp what was apparent to anyone conversant with Ellington and his ways. “It was obvious when I was smarter about the band,” he later said, “that he needed [it] just for his compositions, to hear what they sounded like. . . . I think that the fact of the public recognizing the great Duke Ellington leading a great band—and Duke was obviously the most imposing of bandleaders—I think that was necessary to satisfy his ego.” So Granz chose instead to go after Hodges, who was willing to be lured. Ellington and the taciturn saxophonist had long had an abrasive relationship, mainly because Hodges resented having been suckered into accepting flat fees for riffs that his boss spun into big-money songs. “When Pop turned some of their songs into hits, Rab wanted the deal changed, and when he was refused he became unhappy,” Mercer recalled. “That explains why he would sometimes turn toward the piano onstage and mime counting money.”

By 1951 Hodges’s long-brewing spite was starting to boil over. The cornet player Ruby Braff testified to its intensity:

Duke and Johnny Hodges had long periods when they didn’t speak to each other. At one time they lived in the same apartment block. I was waiting with Johnny Hodges outside the building for a cab one time when Duke came down, also looking for a cab. They didn’t speak but Johnny said to me loudly, “What do you think about a guy who has to have a whole band to say what he wants to say? What do you think about a guy like Louis Armstrong, who can speak for himself all on his own and make the whole world listen?”

Hodges’s abrupt departure took Ellington by surprise. “He was incredibly

égoiste

in the French sense,” Granz recalled. “It disturbed him equally if the room service didn’t work somewhere, or if Johnny Hodges quit the band. Both upset his life, and he hated it. So he was really piqued when I took Johnny away.” More than that, he knew that Hodges had become the very essence of the band’s sound. Clark Terry later said that “even when he’s playing a harmony part in the section you can feel him through the whole band.” Not since Tricky Sam Nanton’s death had he lost a player whose departure was so devastating, and Hodges added insult to injury by scoring a jukebox hit with “Castle Rock,” a jump tune whose R & B–style riffs appealed to the same blacks who were deserting Ellington in droves.

The next man to abandon ship was Billy Strayhorn, though it took him longer to break with the band and his departure was never completely clear-cut. Strayhorn had started pulling away from Ellington in the wake of

Beggar’s Holiday

, and the process accelerated after an eye-opening chat with Lennie Hayton, a veteran Hollywood arranger who had recently married Lena Horne. Strayhorn mentioned that he had no formal publishing agreement with Ellington, and Hayton replied that he had to negotiate a deal at once. He then had a talk with Leonard Feather about the nuts and bolts of the music-publishing business. “The next time I saw him, a week or so later, I asked him if our conversation had been of any use to him,” Feather recalled. “He said, ‘Oh yes, thank you very much. I’ve found the skeletons. They give their regards.’” What he found was that several of his pieces had been copyrighted by Tempo Music in Ellington’s name (or, in some cases, the names of both men). The discovery, Mercer said, hit him between the eyes: “That was the first time I saw any conflict between the old man and Strayhorn. . . . They had a talk about it, but Strayhorn wasn’t satisfied, and he pulled away.”

Feather, who knew both men well, understood that Strayhorn’s anger was in part a response to the paternalism with which Ellington treated him:

Money wasn’t quite the problem. How could it be, when Billy had everything? The problem was the lack of independence that his business problems represented . . . he was totally dependent upon Ellington for all his needs. The actual source of his frustration was artistic. He hadn’t had very much of a chance to do much of his own thing since the whole period of “Chelsea Bridge,” during the ASCAP strike. Surely he knew he wasn’t being acknowledged for many of the things he was doing. He was obviously frustrated as an artist. He decided it was time to do something about it.

That cut to the heart of the matter. In recent years Ellington had used his protégé more as an arranger than as a composer—at least sixty of his vocal charts were played on

Your Saturday Date with the Duke

—and when he gave Strayhorn credit for his work, it was only when it suited him to do so. Onstage he was careful to acknowledge Strayhorn’s contributions, though his habitual use of the royal “we” confused the issue. At the 1944 Carnegie Hall premiere of

Perfume Suite,

for instance, Ellington announced from the stage that the work had been “prepared by Billy Strayhorn and myself,” but the

New York Times

review described the work as “his [i.e., Ellington’s] ‘Perfume Suite.’” On record he was less scrupulous. It had long been common for the two men to share credit on record labels for songs that, like “Brown Penny” and “Something to Live For,” were the work of Strayhorn alone, and Ellington sometimes even took credit for Strayhorn-written instrumentals like “The Air Conditioned Jungle” and “Flippant Flurry” (both of which were composed with Jimmy Hamilton, who got the same treatment when he wrote the instrumental accompaniment to “Pretty and the Wolf,” Ellington’s comic monologue about the shrewd country girl and the slick city man).

For years Strayhorn had looked the other way, presumably out of gratitude for all that Ellington had done for him. But gratitude, like guilt, is a rope that wears thin, and his failure to receive credit for

Masterpieces by Ellington

may have put an end to his patience. Nat Cole’s 1949 recording of “Lush Life” had brought his name to the attention of a wider public, and after 1951 Strayhorn started working independently of Ellington on compositional projects of his own. He could easily have set up shop as a freelance composer-arranger had he wished to do so, but his lack of ambition, coupled with the need to stay out of sight so that he could keep his homosexuality out of the spotlight, made it hard for him to sever his ties to his patron. The result was a depression that led him to start drinking to excess. “He drank just constantly,” a close friend said. “If he was down, he drank to drown it, and if he was up, he drank to celebrate.”

• • •

Unlike Strayhorn’s break with Ellington, the departure of Hodges, Brown, and Greer took place in full view of the public. It thus demanded a countercoup, and Ellington’s response was appropriately dramatic: He talked Louis Bellson, Willie Smith, and his old colleague Juan Tizol into quitting Harry James’s band in March and going to work for him, a masterstroke that some unknown journalistic wag dubbed “the Great James Robbery.” The three men left with James’s blessing—the trumpeter was an Ellington fan—and their presence made an immediate difference. Tizol’s talents were, of course, a well-known quantity, while Smith, best remembered today as the lead saxophonist of Jimmie Lunceford’s band, was as capable of filling Hodges’s chair as anyone in the business. It was Bellson’s hiring that caused the loudest talk. After Buddy Rich, he was jazz’s leading drum virtuoso, a powerhouse whose crisp, extroverted playing was different in every way from Greer’s more subdued style—and he was white. Ellington had never before hired an unequivocally white sideman, and even in 1951, it was daring for him to do so. Bellson feared that his presence might cause trouble, but Ellington finessed the issue: “During our first 1951 tour, just before we headed south for Birmingham, Alabama, he said, ‘We’re going down South so we’re going to make you a Haitian.’ That’s how they described me so we wouldn’t wind up in trouble. I stayed in hotels where they stayed.”

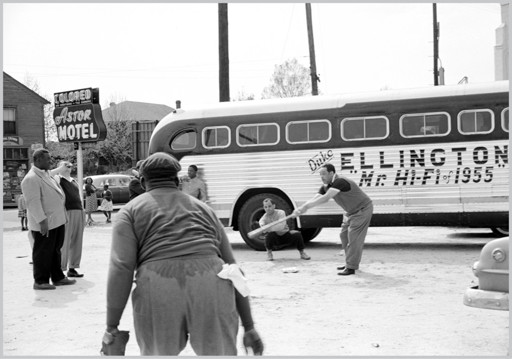

“I stayed where they stayed”: At play in a Florida parking lot, 1955. In the thirties, Ellington and his musicians traveled by rail in private Pullman cars. Two decades later, though, they rode a chartered bus from town to town and stayed in segregated motels like this one whenever they ventured south of the Mason-Dixon Line. Ellington passed off the white drummer Louis Bellson as a Haitian after he joined the band in 1951