Duke (44 page)

Authors: Terry Teachout

“Beige” does indeed recall the structure of “Harlem Air-Shaft,” containing as it does such improbably varied elements as a faux-sophisticated waltz, an interpolated section by Billy Strayhorn that sounds like a super-suave film-music foxtrot, and a Broadway finale that reprises “Come Sunday” to pointless effect, flinging about here-comes-the-coda gestures (including a piano cadenza that bears a suspiciously close resemblance to

Rhapsody in Blue

) for two full minutes. Ellington always found it hard to write convincing finales, and this one sounds as though he ran out of time before figuring out how to weave together the disparate strands of his narrative into a clinching conclusion.

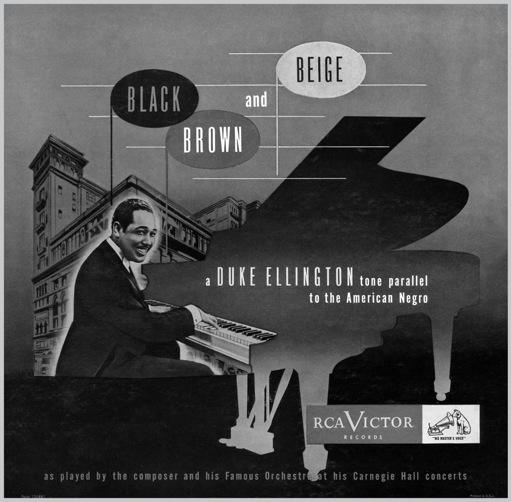

“Well, I guess they didn’t dig it”: Victor’s 1944 album of excerpts from

Black, Brown and Beige

. Ellington believed passionately in the most ambitious of his large-scale compositions but shelved it after Paul Bowles and other critics panned the Carnegie Hall premiere. After 1943, Ellington never again played the complete work in public

In

Music Is My Mistress

Ellington incorrectly remembered the running time of

Black, Brown and Beige

as fifty-seven minutes. Even allowing for the error, a three-movement work that ran for three-quarters of an hour was still a staggering departure from anything that he, or any other jazz composer, had done in the past. That he managed to finish it in six weeks is no less staggering, and no less indicative of its weaknesses, on which the critics pounced. Right though they were, too many of them failed to praise

Black, Brown and Beige

for what it was, just as later critics would make the equal and opposite mistake of praising it for what it wasn’t, claiming for the piece a structural cohesion that it lacks. Eight years after

Reminiscing in Tempo,

Ellington had yet to acquaint himself with the elementary principles of symphonic musical organization known to all classically trained composers, and it showed.

To be sure, he himself insisted that

Black, Brown and Beige

ought not to be judged by the standards of classical music, while simultaneously denying that it was jazz: “We stopped using the word jazz in 1943. That was the point when we didn’t believe in categories.”

¶¶¶¶¶¶¶

Yet it was Ellington’s own decision to premiere the piece in the temple of the American classical-music establishment. By doing so, he exposed himself to the scrutiny of knowledgeable listeners who were naturally inclined to measure his efforts against more traditional yardsticks—some of whom, like Paul Bowles, were also familiar with jazz and thus predisposed to take him seriously, which made their criticisms all the more painful. Had they said what they had to say about

Black, Brown and Beige

in a more encouraging way, he might have learned from the experience and tried again. But they didn’t, and neither did he.

Black, Brown and Beige

might have made a stronger impression had it been recorded in its entirety after the premiere, thus allowing critics and other interested parties to listen to it at leisure. But RCA Victor did not reach an agreement with the American Federation of Musicians until November of 1944, and Eli Oberstein, the label’s new recording director, refused to record the complete work after the AFM strike was settled. He opted instead for eighteen minutes’ worth of excerpts, most of them from “Black” and “Brown,” out of which Ellington chose the handful of snippets that he later played in concert. “What I’m trying to do with my band is to win people over to my bigger composing ideas,” he explained. “That’s why I pared down

B, B and B . . .

maybe they’ll say, ‘Gee, this guy isn’t so bad at all,’ and they’ll listen to the longer and more ambitious works and maybe even enjoy them.” Perhaps—and perhaps, too, he realized that the haste in which he wrote “Beige” compromised its artistic worth so severely as to make the movement unrevivable in its original form.

Whether or not he knew that he had fumbled the ball just short of the goal line, Ellington never admitted to having been shattered by the critics’ response to

Black, Brown and Beige

. He kept a stiff upper lip, describing the piece as “the history of the Negro with no cringing and no bitterness” and saying, “I’d love to see [it] staged on Broadway as an opera or pageant.” He recorded “Black” for Columbia in 1958, and in 1963 he recycled parts of the complete work into a stage revue called

My People

that was received almost as tepidly as the Carnegie Hall premiere. Two years later he made a private recording of “Black,” “Brown,” and most of “Beige” that was not released in his lifetime, and shortly thereafter he included “Come Sunday” in the “concert of sacred music” that he presented at San Francisco’s Grace Cathedral. But he never again played all of

Black, Brown and Beige

after 1943, a fact that speaks eloquently of his enduring hurt.

• • •

What had he been thinking? Was his decision to premiere

Black, Brown and Beige

at Carnegie Hall motivated solely by musical considerations? Or had he also been driven by a different kind of desire? Even though he chose not to lead a conventional middle-class life, Duke Ellington always believed devoutly in preserving the outward appearances of respectability. Trained from childhood onward to “act on behalf of the race,” he was so determined not to embarrass his brethren that he would go to no end of trouble to cover up his deviations from the gentleman’s code of propriety. It made sense that he should have hated the word

jazz,

whose original gutter connotations were still part of America’s collective memory. In 1965 he complained that most Americans “still take it for granted that European music—classical music, if you will—is the only really respectable kind . . . jazz [is] like the kind of man you wouldn’t want your daughter to associate with.” He sought the same respect for his own music, in which the seeming contradictions of his background, part bourgeois and part street, were productively embodied. From “Black and Tan Fantasy” to

Black, Brown and Beige,

he had sought to fuse the nostalgic sentimentality of his mother’s beloved salon ballads with the blunt sexuality of the blues. He longed to make a lady out of jazz—even though she was already his mistress. That was why he brought her to Carnegie Hall: He had something to prove.

Ellington returned to Carnegie Hall six more times between 1943 and 1948, and each time he premiered another new work. None was as grandiose as

Black, Brown and Beige,

but all were conceived specifically for concert-hall performance, and while he would later claim that the Carnegie Hall appearances were “really a series of social-significance thrusts,” they were also meant to solidify his reputation as a composer whose musical significance extended beyond the sphere of jazz. At the first of these concerts, in December of 1943, he grafted musical ambition onto social significance by premiering

New World A-Coming,

a fourteen-minute concerto in one movement for piano and band whose title was borrowed from a newly published book in which the black journalist Roi Ottley called for racial equality in America: “Spiritually aligned with the vast millions of oppressed colored peoples elsewhere in the world, giving American black men strength and numbers, Negroes are no longer in a mood to be placated by pious double-talk—they want some of the gravy of American life.”

While Ellington apparently never got around to reading Ottley’s book, he had his own ideas about the world to which the title referred, imagining it as “a place in the distant future where there would be no war, no greed, no categorization, no nonbelievers, where love was unconditional, and no pronoun was good enough for God.” Accordingly,

New World A-Coming

was subdued and meditative in tone, a spacious work that Barry Ulanov described in

Metronome

as “a series of florid piano passages, in and out of tempo, amplified with great tonal beauty by the orchestra, rich in its chord structure, in its soft, sensuous mood.” It was, in other words, a rhapsody—a jazz counterpart of

Rhapsody in Blue,

to be exact. Ellington was fond of the piece and performed it often in later years, but

New World A-Coming

never caught on with the listening public, no doubt because it contained none of the indelible melodies that make it easier to forgive the twenty-five-year-old George Gershwin his own youthful ignorance of how to put together a large-scale musical composition.

After

New World A-Coming

Ellington moved in a different direction, collaborating with Billy Strayhorn on

Perfume Suite,

first performed at Carnegie Hall in December of 1944. The four movements, “Balcony Serenade,” “Strange Feeling,” “Dancers in Love,” and “Coloratura,” endeavored (in Ellington’s words) “to capture the character usually taken on by a woman who wears . . . different blends of perfume.” In fact, such thematic unity as

Perfume Suite

purported to have was factitious. Ellington simply threw together a quartet of unrelated pieces, the first two of which had previously been written by Strayhorn, and premiered them under a portmanteau title confected after the fact.

********

An attractive but minor effort,

Perfume Suite

is important mainly for what it foreshadowed: After 1944, virtually all of Ellington’s “large-scale” pieces would be multimovement suites to which Strayhorn contributed. These works, as Walter van de Leur explains, were usually “a mix of (retitled) old and new compositions by Ellington and Strayhorn, unified by a programmatic title and explanatory remarks.” Some of them were striking, like

The Deep South Suite

(1946), whose finale, “Happy-Go-Lucky Local,” is a sketch of a rickety train in which Ellington musicalizes the sounds of the bluesy steam whistles that he loved. Others, like

A Tonal Group

(1946),

Liberian Suite

(1947), and

The Symphomaniac

(1948), were less memorable. But even the best of them make no attempt to scale the heights of

Black, Brown and Beige

. They are collections of cameos, no different in scope or style than any of Ellington’s other miniature masterpieces.

Only twice more, in

The Tattooed Bride

(1948) and

A Tone Parallel to Harlem

(1951), did he move beyond his self-imposed limitations to write single-movement works that appeared to essay what Gunther Schuller has called “organically larger form.” But while both of these pieces break the three-minute barrier (each is fourteen minutes long), neither aspires to the systematic thematic development of

Reminiscing in Tempo

or the longer episodes of

Black, Brown and Beige

. Instead they are extended pieces of programmatic “symphonic jazz” that consist of more or less end-stopped musical episodes played in continuous succession, capped by codas that reprise the main themes in order to create an impression of structural unity. And despite their harmonic resourcefulness and matchlessly colorful scoring,

Harlem

and

The Tattooed Bride

are melodically nondescript, making them sound more aimless than they are.

“We didn’t like the tone poems much,” Johnny Hodges admitted. Neither did most of the critics. Howard Taubman’s

New York Times

review of the 1946 Carnegie Hall concert sounded a sharp note of skepticism: “There is, however, the danger of becoming pretentious. The Duke’s best friends had better tell him—some of his program last night was arty, and that, in the words of a number Ellington used to do, ain’t good.”

Time

’s unsigned review was even harsher:

But for fans of the Duke’s “Mood Indigo,” “Sophisticated Lady” and “It Don’t Mean a Thing” days, the concert had the taste of a stale highball. They had come for ginmill stuff and had been served something more like a bad-year champagne. The Duke once more dragged out such pretentious symphonic items as Black, Brown and Beige . . . Until late in the evening, when the band got back to being itself on easy-riding bounce tunes, the whole thing sounded more like André Kostelanetz than a night in Harlem. Four sessions in Carnegie Hall had had an unmistakably mopey, not to say arty, effect on the Duke.

Yet Ellington kept on writing suites long after the band had stopped making annual visits to Carnegie Hall, and after it was evident to all but the most fanatical of his devotees that they were no substitute for the true large-scale works from which he had steered clear ever since

Black, Brown and Beige

. What was the reason for his persistent devotion to a pseudo-form that so often failed to bring out the best in him? In 1956 Ellington said that he was tired of “having the John Hammonds of the world tell me I should stick to three-minute songs.” It seems not to have occurred to him that in writing the suites, he was doing just that.

• • •

Despite the lukewarm response to

Black, Brown and Beige,

Ellington’s Carnegie Hall debut was still a pivotal moment in his career—and a profitable one.

Variety,

as always, took a hardheaded view of its outcome: “Whether or not the concert was an artistic success, it is agreed that the comment it created was invaluable to Ellington’s future. . . . The Duke should cash in plenty henceforth.” And so he did. According to

Billboard,

he received “the greatest pre-performance press ever accorded a jazz man, and on the strength of it William Morris Agency has boosted the price of the aggregation $500 a night” ($6,400 in today’s dollars). The band’s annual gross leaped from $160,000 in 1939 to $405,000 in 1944. Ellington claimed $394,000 in expenses that year, paying himself a weekly salary of $500, and everyone else in the band was paid commensurately. “I heard musicians made this kind of money, but I’d never made any,” said Jimmy Hamilton, who replaced Chauncey Haughton in May of 1943.