Duke (5 page)

Authors: Terry Teachout

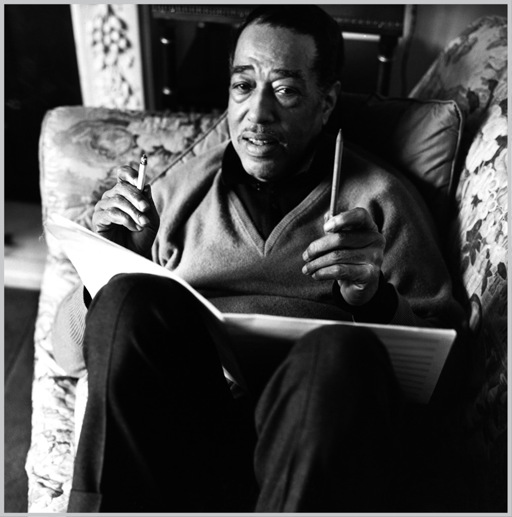

Behind closed doors: Composing at the Dorchester, his favorite London hotel, in 1963. Unposed offstage photos of Ellington are comparatively rare. He went out of his way to shape his public image to his liking—and to keep his private life out of the papers

Yet Ellington almost never fired anyone, having discovered the secret of making unwanted players depart of their own accord before he was forced to cut them loose. A rare exception was the bassist Charles Mingus, who claimed to have goaded Juan Tizol into pulling a knife and chasing him off the bandstand, thus triggering his own dismissal. Mingus set down Ellington’s farewell speech in his autobiography, and even if he embroidered it, as he surely did, you can hear the voice of the master in every petit-point sentence:

“Now, Charles,” he says, looking amused, putting Cartier links into the cuffs of his beautiful handmade shirt, “you could have forewarned me—you left me out of the act entirely! At least you could have let me cue in a few chords as you ran through that Nijinsky routine. . . . When you exited after that I thought, ‘That man’s really afraid of Juan’s knife and at the speed he’s going he’s probably home in bed by now.’ But no, back you came through the same door with your bass still intact. For a moment I was hopeful you’d decided to sit down and play but instead you slashed Juan’s chair in two with a fire axe! Really, Charles, that’s destructive. Everybody knows Juan has a knife but nobody ever took it seriously—he likes to pull it out and show it to people, you understand. So I’m afraid, Charles—I’ve never fired anybody—you’ll have to quit my band. I don’t need any new problems. Juan’s an old problem, I can cope with that, but you seem to have a whole bag of new tricks. I must ask you to be kind enough to give me your notice, Mingus.”

The charming way he says it, it’s like he’s paying you a compliment. Feeling honored, you shake hands and resign.

If it wasn’t true, it should have been. With Ellington, though, the truth was usually more than good enough, and the fact that so little of it can be found in

Music Is My Mistress

is frustrating. He of all people should have left behind a frank memoir, one in which he told the story of how a somewhat better-than-average stride pianist largely devoid of formal musical training managed to turn himself into a great composer—for that is what he was, and why he matters to us today.

In 1944 a journalist dubbed Ellington “the hot Bach,” a comparison that is likely to have vexed him. A decade earlier he had claimed that “you can’t stay in the European conservatory and play the negro music.” He insisted that his own achievement was unique unto itself, so much so that he refused to call his music jazz. “I don’t write jazz,” he said. “I write Negro folk music.” He was wrong: His music is one of the cornerstones of jazz. But he was right about the singularity of his music, just as he himself was as singular as a human being can be, an improbably gaudy bird of paradise who spoke at least one undeniable truth in the self-interview that ends his autobiography:

Q. Can you keep from writing music? Do you write in spite of yourself?

A. I don’t know how strong the chains, cells, and bars are. I’ve never tried to escape.

1

“I JUST COULDN’T BE SHACKLED”

Fortunate Son, 1899–1917

W

ASHINGTON IS A

theme park of power, a city to which fifteen million American tourists travel each year, there to gaze upon the marble monuments that enshrine their past and foreshadow their future. Few go looking for art, though no American city has more museums, and fewer still think of the nation’s capital as a center of jazz, though it’s said that before 1920 Washington was home to more nightclubs than Harlem. But even if that boast smacks of boosterism, it suggests the vitality to which there is ample testimony from those who saw it for themselves. And while only a handful of jazz greats grew up in Washington, one of them was Duke Ellington, who was born in a neighborhood whose name now evokes the black history that he would study in its schools as a boy and make for himself as an adult.

Robert Gould Shaw was the white colonel who commanded the otherwise all-black Fifty-Fourth Regiment at whose head he fell in 1863. Though a century went by before the creation of the Shaw urban renewal area in Washington’s northwest quadrant gave a new name to its principal black neighborhood, the exploits of the Fifty-Fourth and its martyred leader (which would be memorialized by Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Stanford White in Boston’s Shaw Memorial and, later, in the film

Glory

) would have been known to Ellington in his youth. The all-black schools that he attended made a point of teaching their charges such things. Late in life Ellington spoke of how R. A. Boston, his eighth-grade English teacher, had “spent as much time in preaching race pride as she did in teaching English,” explaining to her students that “everywhere you go . . . your responsibility is to command respect for the race.”

By 1900 Washington was home to eighty-seven thousand blacks, a third of the city’s population. While the poorest of them lived on the southwest side of town, most of Washington’s other blacks clustered in the vicinity of U Street, which runs through the center of Shaw. Some were professionals—doctors, nurses, lawyers, teachers, preachers—and a fair number worked for the federal government. A handful taught at nearby Howard University, America’s most prestigious black college, and others at the Preparatory High School for Colored Youth, the country’s first public high school for blacks, which was later renamed after Paul Laurence Dunbar, the black poet who worked for a time at the Library of Congress. Together they comprised the core of the city’s black middle class, a group of Washingtonians as proud of their respectability as they were of their shared history. While they flocked to the fifteen-hundred-seat Howard Theatre, the city’s first black-only theater, to see traveling productions of Broadway shows like

Shuffle Along

and musical groups like James Reese Europe’s Clef Club Orchestra and Will Marion Cook’s Southern Syncopated Orchestra, many preferred

The Evolution of the Negro in Picture, Song, and Story

and the other race-oriented community pageants that were also mounted there. The churchgoers among them regarded ragtime and jazz as disreputable to the point of criminality, preferring to partake of the more decorous fare that was readily available. Glee clubs and choral societies, small orchestras and chamber ensembles, even a short-lived opera company: All could be found in the neighborhood at one time or another.

The goal of these men and women was to lift up their race through economic and cultural self-improvement to the point where whites could no longer ignore their achievements. Booker T. Washington would have approved of their plan wholeheartedly, and most of those who write about black life in turn-of-the-century Washington make a point of mentioning what he said about the city in

Up from Slavery:

During the time I was a student at Washington the city was crowded with coloured people, many of whom had recently come from the South. A large proportion of these people had been drawn to Washington because they felt that they could lead a life of ease there. Others had secured minor government positions, and still another large class was there in the hope of securing Federal positions. A number of coloured men—some of them very strong and brilliant—were in the House of Representatives at that time . . . Then, too, they knew that at all times they could have the protection of the law in the District of Columbia. The public schools in Washington for coloured people were better then than they were elsewhere.

But that was in 1878, a year after the close of the era of Reconstruction that had come in the wake of the Civil War. Soon the yoke of domination was set in place once more. George White, the last black congressman of the post-Reconstruction era, went back home to North Carolina in 1901, shortly after the Southern states disenfranchised their black citizens, and not until 1972 would a state that had once been part of the Confederacy send another black to Congress. Those were the days when books with titles like

The Negro a Beast

and

The Passing of the Great Race

were snapped up by white readers who learned from them that blacks were not only genetically inferior to whites but were breeding so rapidly that Western civilization was at risk. In 1913 Woodrow Wilson, the first Southern-born politician to be elected president since Reconstruction, segregated the federal bureaucracy by administrative fiat, thereby delivering a brutal blow to the fortunes of the city’s middle-class blacks. “I have recently spent several days in Washington,” Booker T. Washington wrote to a colleague shortly afterward, “and I have never seen the colored people so discouraged and bitter as they are at the present time.”

The blacks of U Street, demoralized though they were by Wilson’s actions, kept on striving, but their white neighbors took little note of their efforts. A historian of race relations in Washington later described the ghetto in which they lived as “a secret city all but unknown to the white world round about . . . white citizens of the District of Columbia manifestly were acquainted with only the most obvious facts about how free Negroes lived and knew almost nothing about what they thought.” Neither the well-to-do professionals who owned Victorian row houses nor the laborers who rented tumbledown shacks in the alleys and side streets were thought worthy of coverage by the city’s newspapers, which ignored anything that happened there short of actual violence.

Today that section of town, transformed almost beyond recognition by gentrification, is an integrated neighborhood where condos and renovated row houses change hands for six-figure sums—and where many aging black residents who grew up there can no longer afford to live. A

New York Times

reporter who visited U Street in 2006 described it as “the newest and hottest place in town for getting out on weekends after dark.”

*

But when Duke Ellington was a boy and for long afterward, it was the only place in town where blacks could buy a house, see a movie, eat in a restaurant, rent a hotel room, attend a public school, or shop in a department store. Even the pet cemeteries maintained a color bar. In a 1948 report on racial segregation in Washington, the owner of a dog cemetery explained that “he assumed the dogs would not object, but he was afraid his white customers would.”

Behind the invisible walls that separated them from the rest of Washington, better-off blacks salved their pride by erecting their own walls of disdain. They could never escape the daily shame of segregation, but they held their heads as high as they could, high enough to look down their noses at their less successful neighbors. “I could play the dances,” Sonny Greer said, “but I couldn’t mingle with all the highfalutin doctors and lawyers and all the fancy chicks from the university.” Langston Hughes, who lived in Washington in the twenties, was disgusted by their snobbery: “So many pompous gentlemen never before did I meet. Nor so many ladies with chests swelled like pouter-pigeons whose mouths uttered formal sentences in frightfully correct English.” He was disgusted, too, by the way that the city’s light-skinned blacks treated “the usually darker (although not always poorer) people who work with their hands,” taking scathing note of how “several of the light young ladies [he] knew were not above passing a dark classmate or acquaintance with only the coolest of nods” and “apologies were made by the young men for the less than coffee-and-cream ladies they happened to know.” Such intraracial prejudice was (and is) the dirty little secret of America’s black middle class, and jazzmen of Ellington’s generation were well aware of its existence. The New Orleans bassist Pops Foster minced no words about it: “The worst Jim Crow around New Orleans was what the colored did to themselves. . . . The lighter you were the better they thought you were.”