E=mc2 (14 page)

Authors: David Bodanis

Germany also had the world's best engineers, and a strong university system—despite having expelled so many Jews—and above all, they had that head start: two precious years when Heisenberg and his colleagues had been working full out, while Briggs had mostly been musing at his desk. These were the quirks of fate that would influence who ended up using the equation first. E=mc

2

was far from the pure reaches of Einstein's inked symbols now. The Allied effort would have to go faster.

The German effort would have to be sabotaged.

British intelligence had been monitoring the German program from the beginning, and identified its one weak spot. It was not the uranium—there was too much in Belgium to try to destroy, even if anyone could get at it. Nor was it Heisenberg himself: no assassination squad could reach him in Berlin or Leipzig, and even his family's summer resort in the Bavarian Alps was too far away, and probably too well guarded as well.

The most vulnerable target, rather, was the heavy water. A reactor couldn't fully ignite without slowing down the neutrons from the first atom explosions, so they could find the other nucleus specks, and jostle them to start exploding their hidden energy in turn. Heisenberg had decided on heavy water for that, but it takes a very large factory—using a great amount of energy—to separate that from ordinary water.

Some cautious members of Heisenberg's staff had proposed that Germany construct a factory of its own, safely on German soil, to produce the heavy water. But Heisenberg, backed by army officials, knew there already was a perfectly sound heavy water factory in operation, using the abundant, power-generating waterfalls of Norway. It's true that until recently Norway had been an independent country, but now wasn't it merely a conquered province?

It was a fateful decision, but generations of German nationalists had felt their country was suffocated, entrapped. Heisenberg backed the decision to rely on the Norwegian factory, for he backed the idea of the new Reich's right to dominate all of Europe. Through the war he excitedly visited one subject nation after another, striding through the offices of his onetime colleagues, local collaborators nearby; in the Netherlands explaining to the aghast Hendrik Casimir that although he knew about the concentration camps, "democracy can't develop sufficient energy," and he "wanted Germany to rule."

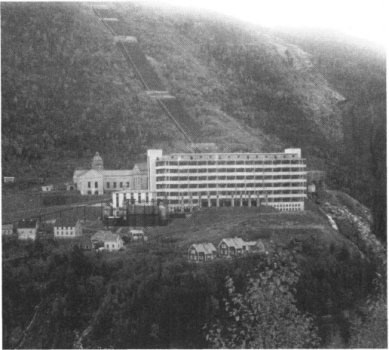

The Norwegian factory was located up a mountainous ravine, at Vemork, 90 miles by winding road from Oslo. Before the war it had produced only 3 gallons—24 pounds—of heavy water a month, for laboratory research. Engineers from the great I. G. Farben industrial combine in Germany had asked for more, and offered to pay above market rates, but the Norwegian managers had refused, unwilling to help Nazis. A few months later the Farben engineers asked again; this time—for the Wehrmacht had destroyed the Norwegian army—they were backed by troops with machine guns. The Vemork staff had no choice but to agree. Production had been accelerated to an annual rate of 3,000 pounds by mid-1941. Now, in mid-1942, it was up to 10,000 pounds per year, steadily shipped to Leipzig, Berlin, and the other centers for atomic research.

There were only a few hundred troops guarding the factory, for the site seemed impregnable. The Norwegian resistance was clearly too small and untrained to be feared for an assault on such a huge factory. The complex was surrounded by barbed wire and arc lights, with only a single suspension bridge giving access. It was located in a setting so deeply cut in the mountains that for over five months of the year shadows from the surrounding peaks kept direct sunlight entirely away, and workers had to be taken up by cable car, to a higher plateau, to get a daily dose of light.

The Norsk Hydro plant at Vemork, Norway

NORSK HYDRO

This was the target the British government chose to attack. If Vemork had been on the coast, then members of the Royal Marines could have tried to go in, but since it was 100 miles inland, a team from the First Airborne Division was chosen. These troops were good. Many were working-class London boys, fists trained from surviving the Depression, and now in their twenties, undergoing more serious training: weapons, radios, explosives. They weren't told where they were going, of course—that would only come on the day of the mission. Until then they believed they were being prepared for a paratrooper competition with the Yanks. That their fate was being directed in an effort to control what Einstein's equation and Rutherford's investigations were leading to—of that they had no idea at all.

Two glider teams took off after dark from northern Scotland, towed by the new high-speed Halifax bombers. There were about thirty troops in all. (Today we think of a typical glider as a single-man device, but then, before helicopters were widespread, they were often much bigger, resembling small cargo airplanes without motors.) It was a terrible night. Huge ore deposits in the mountains they passed seem to have disoriented the compass

of one

of the planes, guiding the pilot into a mountain edge.

The pilot of the other team's glider was an Australian, who found himself caught

in

an impossible dilemma in this disorienting northern hemisphere snowstorm at night: if he stayed with the towing Halifax when it was high, his wings and cable lines would

ice

up so heavily that he would crash. But if he released and flew low too early, swirling gales in the mountains would

toss him away from any

controlled path. The Australian's glider finally released, in heavy cloud, but something went wrong and it too came down in a heavy crash landing.

At each crash site there were a number of survivors, and in both cases a few of the troops—injecting themselves with morphine for their injuries; popping amphetamines to get through the snow—managed to reach local farmhouses for help. But all were soon arrested by German troops or local collaborators. Most were shot immediately; the others were tormented for a few weeks first.

. . .

Just a few years earlier, R. V. Jones had been a promising astronomy researcher at Balliol College, Oxford. Now, barely out of his twenties, he was director of intelligence on the air staff: faced with the sort of ethical dilemma that is an occasion for cleverness at an Oxford dinner; haunting in real life. Thirty Airborne specialists had been sent in, and every single one was dead. The factory hadn't even been reached.

"It fell to me," Jones remembered decades later, "to say whether or not a second raid should be called for. It came all the harder because I should be safe in London, whatever happened to the second raid, and this seemed a singularly unfitting qualification for sending another 30 men to their deaths. . . .

"I reasoned that we had already decided, before the tragedy of the first raid and therefore free from sentiment, that the heavy water plant must be destroyed; casualties must be expected in war, and so if we were right in asking for the first raid we were probably right in asking that it be repeated."

This time the Norwegians themselves took over. Six volunteers who'd made it to Britain were selected. One was an Oslo plumber, another had been an ordinary mechanic. Contemporary records suggest that the British had little confidence the Norwegians would succeed where dozens of crack Airborne troops had failed. Minimal attention, for example, was given to their possible escape afterward. But what else was there to do? As more heavy water continued to be shipped to Germany, work in Leipzig could progress; the Virus House unit in Berlin could catch up as well.

The six Norwegians were trained as well as possible, then sent to a luxurious safe house—S.O.E. Special Training School Number 61—outside Cambridge for final preparations, and also to wait for the weather to clear. There were chatty English girlfriends, and the occasional dinner out in Cambridge. Then in February 1943 the meteorological reports improved; the house suddenly emptied.

After being parachuted in to Norway, they met up with an advance party of a few other Norwegians, which had waited in isolated huts all winter. Together, on cross-country skis, they reached Vemork a few weeks later, at about 9 P.M. on a Sunday night.

"Halfway down we sighted our objective for the first time, below us on the other side The colossus lay like a medieval castle, built in the most inaccessible place, protected by precipices and rivers."

It was the furthermost ripple of what had begun in Einstein's quiet thoughts: a handful of armed Norwegian men, panting in deep snow, staring at a lit fortress in the night. It was clear why the Germans had left only a small guard. The only way in was across the single suspension bridge, over an impassable stone gorge several hundred feet deep. It might be possible in a strong firefight to kill the guards on the bridge, despite their protected emplacements, but if that happened, the Germans would simply start killing the local townspeople. Both sides knew this. When a radio transmitter had been uncovered on Telavaag island the year before, every house and boat was burned, and all the women, and all the children—and of course all the men—who'd lived on the island were sent to concentration camps. Jones in London would probably not accept that again; the nine Norwegians looking down on the factory now definitely wouldn't. But this didn't mean they were going to go back. They had another way in.

From aerial reconnaissance photographs, highly magnified in England, one of the team—Knut Haukelid— had noticed a clump of scrub plants a little further along the gorge. "Where trees grow," he'd remarked, "a man can make his way." One of their members had reconnoitered the day before, to confirm this. They started the climb down, cursing their heavy backpacks, then crossed the river, which was ominously oozing water above its ice, and then cursed their backpacks even more on the climb up to the factory. Since no one wanted to disappoint the others, they all furtively quickened their pace; the speed was soon exhausting.

Outside the factory perimeter they had to rest, sharing chocolate to get some strength. There was a loud noise of turbines, for due to the orders from Leipzig and Berlin, the factory worked on a twenty-four-hour schedule. What do nine highly armed men talk about? One was teased for how he was trying to pick rations out from between his teeth without the others noticing; others spoke, more seriously now, about two young married couples they'd met on the final night before their skiing journey to Vemork. One of the parachuted fighters had been at school with the young man in one of the couples, but at first they'd been scared at coming across armed strangers: they hadn't recognized him. Then when they finally did, each side had realized it was too dangerous to talk, even though the parachuted newcomers were desperate to hear what ordinary life had been like in Norway this past year. They'd had to spend the night aware of the lamps on in the couples' cabin, and the sight of smoke from their hearth fire; busying themselves so they would have no thoughts of home; just checking rifles and grenades and explosives, and waxing their cross-country skis for this assault.

One of the men looked at his watch; the short rest was over. They lifted their packs, and went to the gates. There were advantages to having a big ex-plumber with them, for he now took out oversized wire-cutters and snapped right through the iron. They were inside.

It was the central moment. Heisenberg and the German army's Weapons Bureau had been constructing a "machine": avast apparatus composed of uranium, and trained physicists, and engineers, and electricity supplies, and containment vessels, and neutron sources. Only when every part was in place could the mass from the center of uranium atoms be sucked out of existence, to be replaced by roaring energy in fast, unstoppable E=mc

2

explosions. The heavy water that controlled the flight of the triggering neutrons, slowing them down enough to "ignite" the uranium fuel, was the last part of this machine that had to be put in place. Germany's power—of troops and radar stations and local collaborators and SS inquisitors—had swatted down the British Airborne forces that had tried to obstruct the "machine" that would allow the power of E=mc

2

to emerge.

The nine Norwegian men were now all that were left. One group took up positions outside the guard barracks. Others watched the huge main doors to the factory. Blasting those open would have been possible, but again would have resulted in reprisals. An engineer who'd worked at the factory, though, had told the Resistance about a little-used cable duct that went in from the side. Two of the team, now loaded with all the explosives they'd carried, found it and crawled in.

The workers inside had no love for I. G. Farben, and were only too willing to let them go ahead. Within about ten minutes the charges were set. The workers were sent out, and the two men quickly followed.

At about 1 A.M., there was a slight thud; a brief flash at a few of the windows. The eighteen "cells" that separated out the heavy water were chest high and built of thick steel, looking a bit like overbuilt gas-fired boilers. No explosives that nine men could carry in their climb would totally destroy them. Instead, the Norwegians had set small plastic charges at the bottom of each one. The charges opened up holes, and also sent enough shrapnel flying out to cut exposed pipes.

The warm wind known as the

foehn

had started blowing, and the Norwegians could feel the snow starting to melt on their way back down the gorge. Searchlights came on as well as the air raid sirens, but this didn't matter. The terrain was rough enough to cover the men. As they climbed and then skied away, the heavy water gushed from the factory's drains, rejoining the mountain's streams.