Eagles of the Third Reich: Men of the Luftwaffe in WWII (Stackpole Military History Series) (23 page)

Authors: Samuel W. Mitcham

TABLE 8: LUFTWAFFE ORDER OF BATTLE, “EAGLE DAY,” AUGUST 13, 1940

5th Air Fleet (Stumpff)

X Air Corps (Geisler)

KG 26 (He-111s)

KG 30 (Ju-88s)

I/ZG (Me-110s)

3rd Air Fleet (Sperrle)

VIII Air Corps (Richthofen)

StG 1 (-) (Ju-87s)

StG 2 (Ju-87s)

StG 77 (Ju-87s)

JG 27 (Me-109s)

V Air Corps (Greim)

KG 51 (Ju-88s)

KG 54 (Ju-88s)

KG 55 (He-111s)

IV Air Corps (Pflugbeil)

LG 1 (Ju-88s)

KG 27 (He-111s)

StG 3 (Ju-87s)

3rd Fighter Command (Junck)

JG 2 (Me-109s)

JG 53 (Me-109s)

ZG 2 (Me-110s)

2nd Air Fleet (Kesselring)

I Air Corps (Grauert)

KG 1 (He-111s)

KG 76 (Do-17s and Ju-88s)

KG 77 (Ju-88s)

II Air Corps (Loerzer)

KG 2 (Do-17s)

KG 3 (Do-17s)

KG 53 (He-111s)

II/StG 1 (Ju-87s)

IV/LG 1 (Ju-87s)

Gruppe 210 (Me-109s and Me-110s)

9th Air Division (Coeler)

KG 4 (He-111s and Ju-88s)

I/KG 40 (Ju-88s and FW-200s)

KG 100 (He-111 “Pathfinders”)

1st Night Fighter Division (Kammhuber)

NJG 1 (Me-110s)

2nd Fighter Command (Doering)

JG 3 (Me-109s)

JG 26 (Me-109s)

JG 51 (Me-109s)

JG 52 (Me-109s)

JG 54 (Me-109s)

ZG 26 (Me-110s)

ZG 76 (=) (Me-110s)

Source: Bekker, p. 545.

Eagle Day started badly for the Germans. Because of poor weather, Kesselring had to cancel his part of the morning’s operation. To the South, Sperrle committed his air fleet, which included Richthofen’s Stukas. The weather improved as the day wore on, and Kesselring committed his forces in the afternoon. Like Sperrle’s units, they launched a number of heavy raids against a variety of targets but did not concentrate against Fighter Command—a major German failure through most of the battle.

In all, the Luftwaffe flew 1,485 sorties (most of them by fighters) against 727 by Fighter Command. The Germans lost forty-five aircraft (only nine of which were Me-109s) against thirteen for the R.A.F. The Me-110s and the Stukas, which climbed slowly after diving, had been particularly hard hit. The Me-110, in fact, was a major disappointment. Designed as a bomber escort, it had been unable to protect either the bombers or itself from the Spitfires and Hurricanes. During the early stages of the Battle of Britain it was proven to be technologically inferior to modern enemy aircraft, although Goering refused to withdraw it from the battle. In fact, he ordered that Me-109 units be detached to escort Me-110 units, so the Battle of Britain saw the absurd spectacle of fighters flying escort missions for other fighters!

16

The next three days were just as dismal as Eagle Day had been. The Luftwaffe lost nineteen aircraft on the August 14, seventy-five on the fifteenth, and forty-five on the sixteenth. R.A.F. losses were eight, thirty-four, and twenty-one, respectively. The weather cancelled most operations on the sevnteenth, but on the eighteenth, Fighter Command shot down seventy-one German airplanes and lost only twenty-seven itself. Goering and his intelligence branch now estimated that the British had only 160 fighter aircraft left; they only missed the mark by 590 planes. Still, Goering was far from satisfied with the Luftwaffe’s performance. He pulled the slow Stukas out of the battle and, on the 19th, held a meeting at Cape Blanc-Nez. Every leader down to squadron level heard the Reichsmarschall loudly reprimand the Luftwaffe’s pilots for a lack of aggressiveness. It was the first time the flyers had felt the rough side of his tongue. Goering also changed his tactics. No longer were naval vessels, radar sites, or military facilities to be the focus of operations. From now on his pilots were to concentrate exclusively against the enemy air forces in southeast England: its aircraft, its oil depots, and its sector stations, the nerve centers of the R.A.F.

17

There were also personnel changes. Kurt von Doering was replaced as Fighter Commander 2 by

Pour le Merite

–holder Col. Theo Osterkamp, commander of the 51st Fighter Wing, a seasoned veteran who had shot down thirty-two enemy airplanes in World War I and six more in the battles of France and Britain. Osterkamp, who was forty-eight years old in 1940, was eventually promoted to lieutenant general and was fighter commander Italy later in the war.

18

This rare ace of both world wars was replaced as commander of JG 51 by Maj. Werner Moelders, a twenty-eight-year-old group commander in the 53d Fighter Wing. In the succeeding days other wing and group commanders were also replaced by younger men, in whom Goering had greater faith.

The Cape Blanc-Nez meeting ended the first phase of the Battle of Britain. The Reichsmarschall’s tough words, plus the changes in tactics, opened the second phase, which came very near to winning the war for the Third Reich. Goering had correctly assumed that the R.A.F. would commit its precious fighters for the defense of their bases.

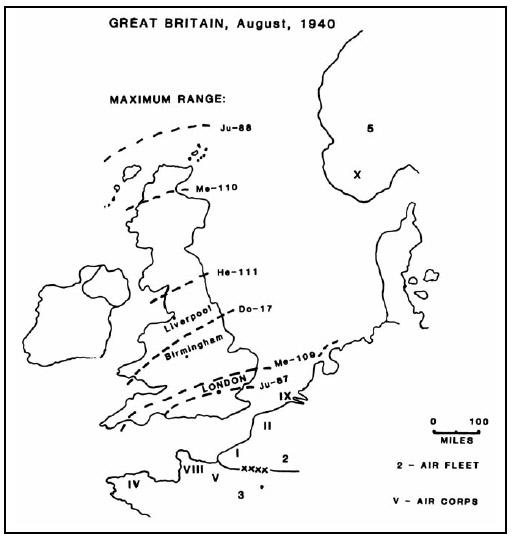

The second phase of the Battle of Britain began when the weather cleared on August 24 (see Map

5

). On the twenty-fifth the Fighter Command airfield and communications center at Warmwell was severely damaged, and the next day the Debden and Southhampton airfields suffered the same fate. The airfields at Rochford and Eastchurch were attacked on the 27th, and the big airfield at Biggin Hill was raided twice and severely damaged on August 29. On the 31st the Luftwaffe made its biggest effort to date, launching 1,450 daylight sorties against Fighter Command bases at Biggin Hill, Debden, Hornchurch, Croydon, and Eastchurch. Biggin Hill was visited again on September 1, Lympne and Hornchurch on the 2nd, North Weald and West Mall -ing on the 3rd, Lympe and Eastchurch again on the 4th, and Biggin Hill once again on the 5th. As a result the Biggin Hill air base was operating at one-third capacity on September 6, and several others were incapable of functioning normally. As Goering predicted, the R.A.F. committed its fighters to the battle for the airfields of southeastern England. In the period August 24 to September 6, 1940, the R.A.F. lost 273 fighters, against 308 Luftwaffe aircraft. During the first three days of September, the Luftwaffe had destroyed sixty-two vital British fighters, at a cost of only forty-three German airplanes. In the decisive category of fighter aircraft, however, the Luftwaffe had lost 146 Me-109s, but they had shot down 208 Spitfires and Hurricanes. British factories could no longer make good Fighter Command’s losses, because casualties exceeded production. The R.A.F.’s frontline strength remained more or less constant at 650 fighters, but the number in reserve declined from 518 in the first week of June to 292 by September 7.

19

Also, for the first time, Fighter Command was experiencing a shortage of trained pilots. It had lost about 300 trained pilots in France and Flanders, and there had been a continual drain since. In the week of August 24-September 1, it lost 231 pilots killed, wounded, or missing—more than 20 percent of its pilot strength in a single week. By the first week in September, the average British fighter squadron had only sixteen pilots out of a normal complement of twenty-six.

20

The survivors had to take up the slack by flying three or four missions a day—a physical and mental strain that could not be kept up indefinitely.

Map 5: Great Britain, August 1940

Map 5: Great Britain, August 1940

Fighter Command’s junior leaders, so essential to a successful air battle, were also disappearing. In July and August, 24 percent of its squadron leaders and 40 percent of its flight commanders had been killed or seriously wounded.

21

The R.A.F. Fighter Command was clearly nearing its breaking point. Air Chief Marshal Dowding was faced with two choices: lose the entire Fighter Command to attrition, or withdraw it north of London, out of the range of the Me-109s. If he did this, however, Germany would control the Channel and the airspace over southeastern England—including the invasion beaches. Either choice would mean a German victory and the fall of the United Kingdom. “What we need now,” Dowding muttered, “is a miracle.”

22

He got one. England’s savior was the same unlikely one who halted the panzers near Dunkirk: Adolf Hitler. The R.A.F. Bomber Command, beginning on August 25, made five minor raids on Berlin in eleven days, doing little material damage but infuriating the Fuehrer. On September 4, Hitler publicly announced: “When they declare that they will attack our cities in great strength, then we will erase theirs!”

23

Supported by Jeschonnek, he ordered massive retaliatory daylight bombing attacks on London, diverting the Luftwaffe from what should have been its real objective: air superiority over the invasion beaches.

Goering saw that terror bombing for retribution’s sake was a mistake. He asked Jeschonnek why he supported it. The chief of staff replied that it would force the British to sue for peace. The Reichsmarschall then asked him if he thought Germany would surrender if Berlin were bombed into ruins. No, Jeschonnek replied, but British morale was made of more fragile stuff than German morale. “That,” Goering responded, “is where you are wrong.”

24

However, if Goering expressed any objections to Hitler himself about meddling in his battle plan, that protest could not have been strong and has not come down to us.