Eagles of the Third Reich: Men of the Luftwaffe in WWII (Stackpole Military History Series) (27 page)

Authors: Samuel W. Mitcham

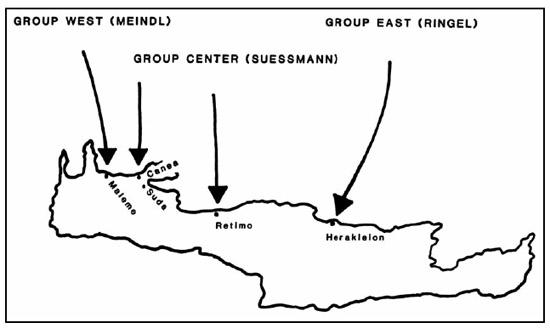

Map 6: Crete, 1941

Map 6: Crete, 1941

Richthofen’s first task, however, was to establish air supremacy over the battlefield from the very first day of operations. Attack-day had to be postponed until the third week in May because of logistical problems. It was necessary, for example, to stockpile 792,000 gallons of aviation fuel for XI Air Corps alone. All of this fuel had to be transported over Balkan roads and/or railroads, which were chaotic enough even in peacetime. Of course VIII Air Corps also had to be supplied, so it was not until May 20 that the assault could begin. Between 5:30

A

.

M

. and 6

A

.

M

. that day, Baron von Richthofen’s fighters and dive-bombers struck the British airfields at Maleme, Heraklion, and Canea, completely neutralizing the Allied air defenses. Only seven of the 493 Ju-52s employed that day were lost.

25

Richthofen’s initial air attack was about the only success the Germans experienced on the first morning of the battle. Enemy resistance was much heavier than anticipated. Many paratroopers were killed by enemy infantrymen before they touched the ground or could disengage their parachutes. Many of those who survived were instantly pinned down and unable to reach their weapons containers, which contained their mortars and crew-served machine guns. Col. Richard Heidrich’s 3rd Parachute Regiment was cut to ribbons south of Retimo, where it was surrounded by about a brigade of Australians. Heidrich did well to save the remnants of his command; seizing the airfield was totally out of the question.

26

Elsewhere, Major General Suessmann, the commander of the 7th Air Division and Group Center, was killed instantly when his tow-cable broke and his glider crashed into the Aegean Sea, many miles closer to Athens than to Crete. Shortly afterwards, Major General Meindl was seriously wounded by a burst of machine-gun fire from a New Zealand unit. Eleventh Air Corps had thus lost two of its three group commanders just as the battle was beginning. Confusion reigned for the rest of the day as parachute drops were badly scattered and the German units were unable to form up due to enemy opposition. Individual paratroopers fought on under the ranking officer or NCO available. Surviving officers did not know where their men were and privates often could not find their own squads or commanders and did not even know if they were alive. The fighting evolved into a series of uncoordinated small-unit actions, with the Allies definitely getting the better of it. The para-troopers of Lieutenant General Ringel’s Group East were also decimated near Heraklion, and the German naval flotilla, carrying desperately needed reinforcements and heavy weapons from the mainland and the German-held island of Milos, was turned back by the British Mediterranean Fleet. As night fell, not one of the four vital airfields was in German hands. Student’s men had, however, scored one important victory: during the afternoon, two detachments of the assault regiment, led by a first lieutenant and the regimental surgeon, had captured Hill 107 overlooking Maleme airfield with pistols and hand grenades. They had no heavy weapons and were almost out of ammunition, but the New Zealanders failed to counterattack. It was the turning point of the battle. That night Student decided to shift the focus of the attack to Maleme. He ordered the Ju-52s carrying elements of the 5th Mountain Division to crashland on the beaches west of Maleme the following day. This, of course, was a very expensive way to ferry in reinforcements and supplies, but it worked. Richthofen’s Stukas also played a major role in the Battle of Maleme by fiercely protecting the defenders of Hill 107. Nearby New Zealand assembly areas were bombed and strafed, and Freyberg’s troops were completely pinned down by the dive-bombers, while Col. Hermann Ramcke (who had replaced Meindl) tried to secure the airfield. At 4

P

.

M

. a flight of Ju-52s carrying elements of a reinforced mountain battalion landed on the airfield, despite heavy enemy artillery and machine-gun fire. Several aircraft were destroyed, but the town of Maleme was captured by 5

P

.

M

., and the airfield was made safe. Before nightfall, the entire 100th Mountain Infantry Regiment (Col. Willibald Utz) had landed at Maleme. The following day Lieutenant General Ringel was given command of Group West, and three more battalions of his 5th Mountain Division landed at Maleme.

27

“Maleme was like the gate of hell,” General Ringel later reported. Eighty Ju-52s—every third transport to land—were destroyed. The single runway was cleared by pushing the damaged transports off with a captured British tank. Bekker described the sides of the airstrip as a “giant aircraft cemetery.”

28

It was nevertheless secured by the morning of the twenty-second. Although the Battle of Crete was not yet decided, the crisis had, for the moment, passed. Richthofen was now in a position to turn his attentions to his other mission: clearing the sea lanes to Crete. This meant engaging the British Mediterranean Fleet in an air-sea battle, something the baron and his pilots were extremely eager to do.

The air-sea battle had actually begun on the twenty-first, when an Italian naval flotilla carrying heavy weapons to Crete was dispersed and ten small vessels sunk by a British task force. Richthofen immediately committed his corps reserve (which he had been withholding for just such an eventuality) against this task force and sank the British destroyer

Juno

and damaged the cruiser

Ajax

. On the twenty-second, however, the battle between Richthofen and Admiral Cunningham became general. At 5:30

A

.

M

. several Stukas, diving from 12,000 feet, bombed the cruisers

Gloucester

and

Fiji

but did not sink them. These vessels then took positions further west, nearer the main fleet (task forces A, B, and D), located about thirty miles west of Crete. Meanwhile, Rear Admiral King’s Task Force C patrolled the waters north of Crete with four cruisers and three destroyers. They located and pursued a German flotilla that was trying to ship heavy weapons to Crete. Just before King could catch the small vessels, however, he was attacked by the Ju-88s and Do-17s from the VIII Air Corps. Two of the cruiser

Naiad

’s gun turrets were knocked out, and her side was ripped open. Her bulkheads held, however, and she managed to limp off at half speed. Meanwhile, the cruiser

Carlisle

suffered a direct hit and her captain was killed, but she also remained afloat.

29

The air-sea battle continued that afternoon when the battleship

Warspite

suffered serious damage under a direct hit and the destroyer

Greyhound

went to the bottom following a Stuka attack. Admiral King ordered the destroyers

Kandahar

and

Kingston

to pick up survivors from the

Greyhound

and recalled the cruisers

Gloucester

and

Fiji

from the west, to provide them with antiaircraft covering fire. King did not realize that the cruisers had expended virtually their entire supply of antiaircraft ammunition that morning. When he was informed of this fact, he promptly ordered them to retire, but it was already too late. Several schwarms of Ju-87s and Ju-88s spotted the

Gloucester

and attacked her. Soon her entire deck was afire, and her damage control teams were unable to check the blazes. At 4

P

.

M

. the flames must have reached her fuel or her magazine, for she was racked by an internal explosion and sank. Admiral King made the difficult though necessary decision to leave the crew of the

Gloucester

to its fate, because any vessels attempting a rescue would only themselves fall victim to the Stukas and Ju-88s. About 500 members of the crew were saved during the night by the small German flotilla and by Luftwaffe sea rescue aircraft.

30

Escorted by destroyers, the

Fiji

attempted to escape to the main British naval base at Alexandria, Egypt. At 5:45

P

.

M

. she was spotted by a lone Me-109 fighter-bomber carrying a single 500-pound bomb. As fate would have it, the bomb struck the

Fiji

on the side, below the water line, and exploded, fracturing the hull. It was listing heavily and was almost defenseless when a second Me-109 (summoned by the first pilot), attacked and scored a direct hit. The

Fiji

capsized at 7:15

P

.

M

.

31

During the night of May 22–23, the destroyers

Kelly

and

Kashmir

shelled the German airfield at Maleme and, when dawn broke, were off the northern coast of Crete, in a position to block any German-Italian seaborne attempt to bring heavy weapons to the parachute and mountain troops on Crete. The sun did not bring to light Axis ships, however, but rather twenty-four Ju-87s from I Group, 2nd Stuka Wing. Both destroyers were soon sunk by direct hits. Despite exhortations from Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Admiral Cunningham signaled London that they would have to accept defeat: the losses involved were simply too heavy for the Royal Navy to continue trying to prevent seaborne landings at Crete. The British had at last learned the lesson that Gen. Billy Mitchell had tried to teach the Americans in the early 1930s: ships without air cover could not survive against an enemy with air superiority. Richthofen’s air-sea victory had opened the German supply lines. The Battle of Crete was now decided, although Churchill was not yet ready to recognize the fact. New German ground units with heavy weapons and artillery now arrived and, by nightfall on the twenty-third, had linked up with Group Center west of Canea.

32

The British Mediterranean Fleet had not yet seen the last of the Luftwaffe at Crete, however, for it was ordered to reinforce and resupply Freyberg’s corps. The aircraft carrier

Formidable

was committed to a battle to provide air support for the fleet, but it suffered two direct hits from German bombers on the twenty-sixth and had to be withdrawn. By the next day the first panzers were landed on the northern coast of Crete and Gen. Sir Archibald Wavell, the commander-in-chief, Mediterranean, signaled London that the island was untenable. The battered Mediterranean Fleet now conducted the evacuation of Crete, under continuous harassment from VIII Air Corps, and suffered further damage. The Battle of Crete ended on June 1, when the last Allied troops on the island surrendered. Table

9

shows the losses suffered by the British fleet during the battle.

| |

| TABLE 9: THE BRITISH MEDITERRANEAN FLEET, MAY 1941 | |

Battleships | |

Barham | Damaged, May 27 |

Queen Elizabeth | |

Valiant | Damaged, May 22 |

Warspite | Severely damaged, May 22 |

Cruisers | |

Gloucester | Sunk, May 22 |

Fiji | Sunk, May 22 |

Orion | Severely damaged, May 29 |

Ajax | Damaged, May 22 and 28 |

Perth | Severely damaged, May 30 |

Dido | Damaged, May 29 |

Naiad | Severely damaged, May 22 |

Phoebe | |

Coventry | |

Calcutta | Sunk, June 2 |

Carlisle | Damaged, May 22 |

Destroyers | |

Napier | Damaged, May 30 |

Nizam | |

Kandahar | |

Kingston | |

Kimberly | |

Kelly | Sunk, May 23 |

Kashmir | Sunk, May 23 |

Kipling | |

Kelvin | Damaged, May 30 |

Juno | Sunk, May 21 |

Janus | |

Jervis | |

Jackal | |

Jaguar | |

Nubian | Damaged, May 26 |

Isis | |

Imperial | Sunk, May 29 |

Ilex | |

Hero | |

Hotspur | |

Hereward | Sunk, May 29 |

Hasty | |

Havock | |

Griffin | |

Greyhound | Sunk, May 22 |

Decoy | Damaged, May 29 |

Defender | |

Stuart | |

Voyager | |

Vendetta | |

Totals: 3 cruisers and 6 destroyers sunk; 3 battleships, 1 carrier, 7 cruisers, and 4 destroyers damaged. | |

|