Early Dynastic Egypt (32 page)

16) with the exception of cedar, the southern limit of which appears to have been Mt. Hermon on the present-day Israeli-Lebanese border (Ward 1991:14). The apparent intensity of Egyptian activity in southern Palestine in the reign of Narmer—sherds incised with his

serekh

have been found at Tell Arad (Amiran 1974, 1976) and Tel Erani (see above) as well as at Nahal Tillah —seems to represent the end of the second phase of Egyptian settlement in the region. After the early First Dynasty (EBII) the evidence points to a marked decline in Egypt’s contacts with southern Palestine (Hartung

1994:112). The Egyptian presence at En Besor seems to have been maintained at least until the reign of Anedjib, but contacts with other sites in the region decrease dramatically. The Sinai coastal route to Palestine apparently fell into disuse at the same time, no doubt linked to this reduction in Egyptian activity (Ben-Tor 1991:5). The growing authority and independence of southern Palestinian cities may have been a factor, whilst an increase in maritime trade may have released the Egyptians from their dependence on southern Palestine as a source of commodities (Brandl 1992:447–8). The fundamental change in Egyptian relations with southern Palestine mirrors developments in Nubia (see below). Instead of a ‘broad border-zone occupied by intermixed Egyptian and native trading-posts and villages’ in the northern Sinai and southern Palestine (Seidlmayer 1996b: 113), Egypt seems to have adopted a more exploitative and hostile attitude. This is reflected in military campaigns which are recorded from the beginning of the First Dynasty.

Military activity

Given the lack of any evidence for a military aspect to the late Predynastic and First Dynasty Egyptian presence in southern Palestine, the campaigns launched by Egypt’s early rulers perhaps amounted to nothing more than a series of occasional, punitive raids designed to ensure the continued co-operation of the local populace. It has been suggested that the Narmer Palette records a military campaign against Palestine. The determinative accompanying one of the king’s slain enemies does indeed bear a close resemblance to a ‘desert kite’, a stone-walled enclosure used by the nomadic shepherds of southern Palestine. It is possible, therefore, that the campaigns undertaken by the king to secure the borders of his newly unified realm included a skirmish with the people on Egypt’s north-eastern border. More certain evidence for Narmer’s dealings with Palestine is provided by a fragment of inscribed ivory from his tomb complex at Abydos (B17). It shows a bearded man of Asiatic appearance, wearing a curious pendulous head-dress and a long, dappled robe. The man holds a branch or plant in one hand and is depicted in a stooping posture, perhaps paying homage to the Egyptian king (Petrie 1901: pl. IV.4–5).

There are contemporary inscriptions suggesting military campaigns against ‘the Asiatics’ by several Early Dynastic kings (Figure 5.1). An ivory label of Den—originally attached to a pair of his sandals—from his tomb at Abydos shows the king smiting a kneeling captive (Amélineau 1899: pl. XXXIII; Spencer 1980:65, pls 49, 53 [Cat. 460], 1993:87, fig. 67). The caption can be translated as ‘First time of smiting the easterner(s)’, though the label could record a ritual event rather than an actual campaign. The identification of the conquered enemy is further aided by details of the local landscape which are depicted behind the captive. The sandy, hilly topography confirms the location of the campaign as the arid lands to the north-east of Egypt, in other words the Sinai or southern Palestine. The occurrence of Den’s name at En Besor (see above) confirms Egyptian activity in southern Palestine during his reign. Further evidence that Den carried

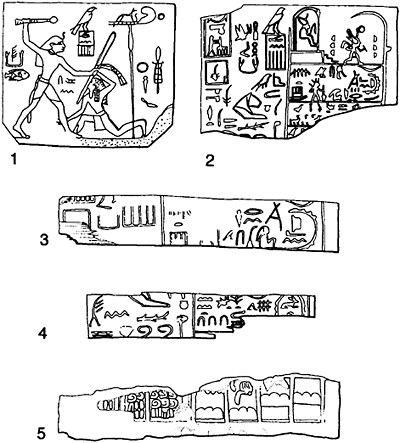

Figure 5.1

Campaigns against southern Palestine.

Iconographic evidence for Egyptian aggression (real or ideological) against lands to the north-east: (1) year label of king Den from Abydos, bearing the legend ‘First time of smiting the east(erners)’ (after Spencer 1980: pl. 53, cat. 460); (2)

(3) (4) year labels of Den referring to the destruction of enemy fortresses, presumably in southern Palestine; on the most complete label, the reference to the destruction of a fortress is at the right- hand side of the second register (after Petrie 1900: pl. XV.16–18); (5) fragment of stone relief from a building at

Hierakonpolis erected under Khasekhemwy, giving the names of (conquered?) foreign localities (after Quibell and Green 1902: pl. XXIII, bottom). Not to same scale.

out campaigns against Western Asia is provided by four fragmentary year labels from Abydos (Petrie 1900: pl. XV.16–18, 1902: pl. XI.8). They fall into two pairs of similar or identical inscriptions. Each mentions a fortified oval enclosure, preceded by the sign

wp,

‘open’, probably with the meaning ‘breach’ (cf. Weill 1961:21). On one type of label, the enclosure is labelled as

wn(t),

a word which can be translated as ‘stronghold’ from its occurrence in the Old Kingdom Inscription of Weni (Sethe 1903:103, line 12; Lichtheim 1975:20; cf. Weill 1961:18). Like the

wnwt

destroyed by Weni, the stronghold(s) breached by Den probably lay in northern Sinai or southern Palestine. The other two enclosures, on the second type of label, are named as

3 n

or, more simply,

3n.

It is tempting to interpret this as the Semitic word ‘En/‘Ain: ‘well’ (Weill 1961:21), referring to a settlement founded at the site of a spring (for example, En Besor). In each case the enclosure is shown breached on one side, and the hoe depicted next to it probably symbolises destruction. The presence of Palestinian vassals or captives at the Egyptian royal court is again hinted at later in the First Dynasty. An ivory gaming-rod from the tomb of Qaa at Abydos shows a bound Asiatic captive. The hieroglyphs above his head clearly label him as an inhabitant of

S t

(Syria-Palestine) (Petrie 1900: pl. XII.12–13=pl. XVII.30).

At the end of the Second Dynasty, sealings of Sekhemib include the epithet

ỉnw h 3st,

‘conqueror of a foreign land’ (or, alternatively, ‘foreign tribute’), suggesting military activity on Egypt’s frontiers. A sealing of Peribsen from his tomb at Abydos bears the similar epithet

ỉnw S t,

‘conqueror/tribute of Setjet’. Whilst Setjet usually signifies Syria-Palestine, the determinative in this case is the town sign, rather than the sign for ‘foreign land’. This suggests that Setjet was a locality on Egypt’s north-eastern border, possibly Sethroë. The late Second Dynasty witnessed fundamental changes in Egypt’s relationship with Palestine. In the reign of Khasekhemwy an official is attested, for the first time, with the title

ỉmỉ-r(3) h 3st,

‘overseer of foreign land(s)’. If this refers to southern Palestine rather than the Sinai (see below), it indicates that a new era had begun in Near Eastern geo-politics. Egypt was now secure enough within its own borders to place its dealings with Palestine on a proper administrative footing.

Imports from Syria-Palestine in the Early Dynastic period

It is likely that the lucrative and important trade with southern Palestine remained a state monopoly throughout the Early Dynastic period. The preservation of such a monopoly may have been one of the factors which contributed to the further centralisation of the state during the first three dynasties (Marfoe 1987:26–8). An idea of the volume of Early Dynastic trade may be gained from the huge quantities of copper found in some élite and royal burials of the First and Second Dynasties. Tomb S3471 at North Saqqara, dating to the reign of Djer, contained some 700 copper objects, including 75 ‘ingots’ (Marfoe 1987:26). A smaller but similar hoard was found in the tomb of Khasekhemwy at

Abydos. By the Fifth Dynasty, copper had become sufficiently common for a long drain- pipe to be made of the metal for Sahura’s funerary complex (Marfoe 1987:26).

The other main archaeological evidence for trade contact between Egypt and the Near East in the Early Dynastic period consists of a large number of imported Syro-Palestinian vessels found in royal and private tombs, particularly during the mid-late First Dynasty (Adams and Porat 1996). Precise parallels excavated in Israel have helped to confirm the correlation between the First Dynasty in Egypt and the EBII period in Palestine, one of the best-attested chronological connections in Near Eastern archaeology (Bourriau 1981:128). Imported Syro-Palestinian vessels were first identified in Egypt by Petrie in the royal tombs of Djer, Den and Semerkhet at Abydos, and were thus nicknamed ‘Abydos ware’. In fact, this group of foreign pottery comprises three distinct wares. The first, and most common, is a red-polished ware characterised by a drab or brown fabric with gritty mineral inclusions, fired at relatively low temperatures. The second type is a ware with a distinctive metallic ring, produced by high firing; the surface may be plain, burnished, lattice-burnished or combed. The third and rarest ware is of a similar fabric to the red-polished ware, but light-faced or white-slipped, with painted geometric designs in brown or red (Kantor 1965:15). Painted ware is not found in Egypt before the reign of Den (Adams and Porat 1996:98), and is most common in contexts dating to the end of the First Dynasty. The first two wares are diagnostic for EBII Palestine, Byblos and other southern Syrian sites. Comparative

petrographic analysis

of vessels from Egypt and the Near East indicates that these wares were probably manufactured in northern Israel or the Lebanon, in the vicinity of Mt. Hermon (Adams and Porat 1996:102). Although the light- faced ware also occurs, sporadically, in Phase G of the

Amuq

sites in northern Syria, it too seems to have originated in Palestine, probably in Lower Galilee in the vicinity of Lake Kinneret (Adams and Porat 1996:104). It seems, therefore, that the combination of pottery types represented by these imports was characteristic for Palestine and the Syrian coast, regions which were connected by both land and sea routes to Egypt (Kantor 1965:16). The appearance of painted ware in Egyptian contexts from the reign of Den onwards may indicate a shift in patterns of trade, with Palestine playing an enhanced role compared to the situation earlier in the First Dynasty.

Imported vessels in Egypt occur in a range of shapes, suggesting that they may have been used to transport a variety of commodities (Bourriau 1981:128). Oils and aromatic resins were probably amongst the most important trade goods (O’Connor 1987:33), and a large vessel excavated at Abu Rawash was found to contain a hard black substance, identified as resin (Klasens 1961:113). Scientific analysis—by gas chromatography/ mass spectrometry—of the contents of vessels from the tomb of Djer indicates that vegetable oils were a major imported commodity. However, one vessel apparently contained resin from a member of the pine family, though it is impossible to identify the species more precisely (Serpico and White 1996). The vast majority of imported Syro-Palestinian pottery comes from sites in Lower Egypt, notably North Saqqara. This is not so surprising, given the greater proximity of northern sites to the Near Eastern trade routes. The few imported vessels from Upper Egypt derive exclusively from the royal burial complexes at Abydos. Obviously, there was no difficulty for the king and the royal court in acquiring imported commodities (especially if foreign trade was a royal monopoly). Altogether, some 124 complete or fragmentary Syro-Palestinian vessels are known from Early Dynastic Egyptian contexts, plus several dozen unrestorable fragments. Two-thirds

of the vessels (81) come from tombs dating to the reign of Den. The others range in date from the very early First Dynasty, probably the reign of Narmer (from Abu Rawash tomb 389 [Klasens 1958:37–8]), to the Second Dynasty, with a particular cluster at the end of the First Dynasty in the reigns of Semerkhet and Qaa (29 vessels). The apparent concentration of imports in the reign of Den is more likely to be a reflection of the large number of élite burials of this date, rather than evidence for an upsurge in trading activity, although the latter possibility cannot be ruled out. Similarly, the paucity of evidence for trade with the Near East after the end of the First Dynasty is probably due, to a large extent, to the relatively small number of élite burials which can be securely dated to the Second and Third Dynasties (Kantor 1965:17). The single imported vessel from a Second Dynasty tomb at Helwan suggests that trade contacts did continue, albeit perhaps at a reduced level. Egyptian and Egyptianising objects of Second Dynasty date from Ai in southern Palestine provide further evidence for the continuity of trade between the two regions (Kantor 1965:16), as do the Syro-Palestinian imports found in Old Kingdom contexts.

Other books

Loving Lies by Julie Kavanagh

The Devil's Seal by Peter Tremayne

The Wedding Favor by Unknown

Killings on Jubilee Terrace by Robert Barnard

Pyxis: The Discovery (Pyxis Series) by K.C. Neal

Four Scarpetta Novels by Patricia Cornwell

Picked-Up Pieces by John Updike

A Brooding Beauty by Jillian Eaton

The Potty Mouth at the Table by Laurie Notaro

Better Than Chocolate by Lacey Savage