Early Dynastic Egypt (54 page)

- a fragmentary label of Aha from Abydos, showing a bound prisoner being

- a fragmentary label of Aha from Abydos, showing a bound prisoner being

sacrificed; an officiant plunges a dagger into the prisoner’s breast, while a bowl stands between the two to catch the blood (after Petrie 1901: pl. III.6); (2) a wooden label of Djer from Saqqara, with an identical scene of prisoner sacrifice shown in the top right-hand corner (after Emery 1961:59, fig. 21). Not to same scale.

second register figures bring a bull standard and a panelled rectangle, perhaps representing the royal

serekh.

The procession of totem-bearers on the top register is followed by a smaller figure carrying a spear.

Divine images

The principal goal of cult practice was to bridge the twin realms of the divine and the human and invoke the presence of the gods on earth in their divine images (Baines 1991:91; and see also Figure 8.3). The dedication of divine images and statues is well attested in Early Dynastic sources, particularly those dating to the First and Second Dynasties (cf. Logan 1990:62). The Egyptian word used to describe the action is

ms,

literally ‘to give birth to’ and hence ‘to fashion’. However, there is some debate about the precise meaning of the phrase in relation to divine images. Some scholars think that the activity thus recorded is the dedication of the image by the king to the god, rather than the manufacture of the image (which would not have been carried out by the king himself, though he would doubtless have commissioned the work). In dedicating the image, possibly by means of the ‘opening of the mouth ceremony’, the king would have given life to the statue, and the word

ms

may refer to this aspect of the event. Leaving aside the precise significance of the verb

ms,

there is no doubt that the commissioning and dedication of cult images was a major royal activity in the Early Dynastic period (F.D.Friedman 1995:35). In the annals of the Palermo Stone and its associated fragments, there are some 21 references to the fashioning of divine images in the first two dynasties (Redford 1986:89). Many First Dynasty labels also record the practice. The creation of cult statues validated the king’s own claim to divinity by reinforcing his position as theoretical high priest of every cult and his role as intermediary between gods and humans.

The divine images dedicated by Early Dynastic kings were probably statuettes made from stone or precious metal. The Coptos colossi and a similar stone statue from the early temple at Hierakonpolis represent the earliest surviving cult images of anthropomorphic deities. A number of stone animal sculptures have also survived from the early dynasties, and these are generally assumed to have been cult statues of deities worshipped in animal form. They include a travertine baboon incised with the name of Narmer (perhaps the king who dedicated the image) (E.Schott 1969), a frog of the same material (Cooney and Simpson 1976), and a limestone hippopotamus (Koefoed-Petersen 1951:4, pl. 1). The Sixth Dynasty gold hawk from the temple of Horus at Hierakonpolis (Quibell and Green 1902: pl. XLVII) indicates that cult statues were also made of precious metals. Unsurprisingly, few have survived from antiquity. Cult statues were probably housed and

transported in carrying-chairs (cf. Troy 1986:79–82). Small model carrying-chairs of glazed composition and stone have been found in deposits of early votive offerings (Kemp 1989:93, fig. 33); one of these models may represent the carrying-chair as a deity in its own right, named

(r)p(y)t,

‘she of the carrying-chair’ (Troy 1986:80). The Scorpion macehead shows a number of figures on what appear to be sledges; these may also have been divine cult images (Roth 1993:39, n. 23; cf. Pinch 1993: pls 10, 21b, 24–5). Similar sledge-born figures are shown on a block from the Palace of Apries at Memphis which, although probably of Late Period date (contra Weill 1961:351), has important iconographic links with Early Dynastic religion (cf. Bietak 1994). Given the general conservatism of religious rituals, we may assume that cult statues were carried in procession, and that the appearances of divine

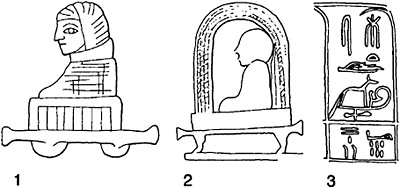

Figure 8.3

Divine images. Representations of cult images from contemporary Early Dynastic sources: (1) female figure on a sledge, possibly a divine image, shown on the Scorpion macehead (after Spencer 1993:56, fig. 36); (2) female figure in a carrying-shrine, again plausibly identified as a divine image, shown on the Narmer macehead (after Quibell 1900: pl.

XXVIB); (3) entry from the third register of the Palermo Stone, referring to a year (in the mid-First Dynasty) as ‘the year of dedicating (an image of the god) Sed’ (after Schäfer 1902: pl. I). Not to same scale.

images in such circumstances were an important feature of Egyptian cult practice in the Early Dynastic period, as they were in the New Kingdom (Kemp 1989:185–8). The open plan characteristic of Early Dynastic provincial shrines may be as much practical as symbolic, designed to accommodate this particular aspect of cult practice (Roth 1993:39).

Votive offerings

From the detailed analysis of Egyptian sources, combined with general observation of contemporary and ancient religious practice, a leading scholar has concluded that individuals visiting a shrine or temple engage in three types of activity: ‘prayer, sacrifice, and the dedication of votive offerings’ (Pinch 1993:333). For the Early Dynastic period, there is a complete absence of textual information or elaborate depictions of religious activity; we therefore remain ignorant about the first two categories of private activity, prayer and sacrifice (but, as we have seen, there is limited evidence for human sacrifice at ritual occasions attended by the king). We are slightly better off when it comes to the dedication of votive offerings since, at several sites, the objects themselves have survived. It is likely that visitors to shrines would have routinely brought with them simple offerings of perishable commodities, especially foodstuffs. On certain (perhaps rare?) occasions, however, a visitor would demonstrate particular piety—and/or concern—by donating an object made specifically for this purpose. In the Early Dynastic period, as in later times, these votive offerings were most often made of glazed composition, although stone and pottery examples are known.

Four sites have yielded large numbers of votive objects which, by their style or archaeological context, can be dated to the Early Dynastic period: Abydos, Hierakonpolis, Elephantine and Tell Ibrahim Awad (see below, under individual site headings, for further information about the archaeology of these early shrines). In addition, a fifth, unprovenanced deposit of early votive material was unearthed by illicit digging in the 1940s or 1950s; it is quite possible that this deposit, too, came from Abydos, although other sites, such as Naqada, have also been proposed (Kemp 1989:79). The date of the material from the first two sites, Abydos and Hierakonpolis, is still the subject of some controversy (Kemp 1968:153). In particular, the excavation of the Hierakonpolis ‘Main Deposit’ was carried out without detailed recording, so that the precise archaeological context of the finds cannot now be established (B.Adams 1977). By, contrast, the Satet temple at Elephantine and the shrine at Tell Ibrahim Awad have both been excavated in modern times, providing reliable stratigraphic evidence for the date of the votive material (Dreyer 1986; van Haarlem 1995, 1996). This in turn provides an important reference point against which to date comparable objects from Abydos and Hierakonpolis. Hence, although some questions remain, an Early Dynastic date for most of the material can be accepted with some confidence.

In its general character, the votive material from the four sites is substantially similar. Most of the objects are made of glazed composition and depict animal or human figures. Natural pebbles and flint nodules, many in suggestive shapes, also occur (Petrie 1902: pl. IX.195–6), whilst stone and ivory figurines are also represented at all four sites. However, within this broad homogeneity, a few notable distinctions emerge which may be attributable to local customs or preferences. Hence, a distinctive feature of the votive material from Hierakonpolis is the frequency of scorpions and scorpion tails, modelled in faience or stone (Kemp 1989:75). Two stone vases, also from the ‘Main Deposit’, were decorated with scorpions in raised relief (Quibell 1900: pls XVII, XXXIII top left, pls XIX.l, XX.l). By contrast, scorpion figurines were not found at Abydos or Elephantine and have not been reported from Tell Ibrahim Awad. It is tempting to make a connection with the late Predynastic king whose ceremonial macehead was found in the same deposit at Hierakonpolis and whose name is read as ‘Scorpion’. However, it is perhaps safer to

attribute the preponderance of scorpion images at Hierakonpolis to an aspect of the local cult. This particular local allegiance may have been acknowledged in the name chosen by a local ruler. At Elephantine, a common type of votive offering is a small, oval, faience plaque, with the head of an animal (apparently a hedgehog) modelled at one end (Kemp 1989:73, fig. 24.1). Forty-one examples of this strange object were recovered from the Satet shrine, but the type is not attested at Abydos or Hierakonpolis (although an object from Abydos described as a ‘rough mud doll’ may be a crude hedgehog plaque [Petrie 1902:28, pl. XII.264]). Recent excavations at Tell Ibrahim Awad have yielded a few examples of ‘hedgehog plaques’, but not in the numbers in which they occur at Elephantine. They may therefore represent a local tradition of worship (although the original purpose of these enigmatic objects is lost in the mists of time). The votive material from the early shrines at Hierakonpolis and Elephantine thus hints at local or regional traditions of belief. This is an aspect of Egyptian culture which is difficult to establish in the face of the overwhelming evidence from a court-inspired ‘great tradition’. None the less, it appears to be an important feature of early civilisation in the Nile valley, manifest in other classes of small object such as stamp-seals and also in the architecture of local shrines (Kemp 1989:65–83, 89–91).

Of course, ‘a votive offering is not simply an artefact, it is the surviving part of an act of worship’ (Pinch 1993:339). Rituals were probably performed ‘to link a votive object with its donor’; and the actual presentation of an offering was, no doubt, accompanied by prayers and perhaps other acts of which no traces have survived. Little is known for certain about who made votive offerings and how they were acquired by donors (Pinch 1993:326–8). It is dangerous to try and deduce the social status of donors from the quality (or lack of it) of their votive offerings (Pinch 1993:344). None the less, a key question about shrines and temples at all periods of Egyptian history is the degree of access enjoyed by members of the general population. From the earliest times, state temples are likely to have been off limits to all but temple personnel, the king and his closest officials. Already in the temple enclosure at Hierakonpolis, constructed in the Second or Third Dynasty, we see the architecture of restricted access (see below). To what extent smaller shrines were accessible to members of a local community remains a moot point. Votive offerings are a potentially useful source of information, if it could be established where they were made and what type of person dedicated them. Unfortunately, these questions are difficult to resolve. There is no doubt that royal workshops producing high- quality craft items existed in Egypt from Predynastic times. However, the marked separation between state and private religion, discussed below, makes it unlikely that the small votive offerings found at sites like Elephantine and Tell Ibrahim Awad (both remote from the centres of Early Dynastic political power) were manufactured in royal workshops. Rather, they were probably produced by skilled craftsmen, either working for their own benefit or attached to the local shrine. How they would have been purchased by donors, operating within a barter economy, is difficult to envisage (Pinch 1993:328). The votive objects from Abydos, Hierakonpolis and Tell Ibrahim Awad were all found in deposits, representing accumulations of material gathered up and buried at periodic intervals long after it was initially dedicated. Only at Elephantine were votive offerings found

in situ,

on the floor of the Satet shrine. Whether the donors themselves were able to penetrate the inner rooms of the shrine, or whether the offerings were carried there by priests, cannot be established. Evidence from the New Kingdom would favour the latter

interpretation, but the situation may well have been different in the Early Dynastic period. To summarise, for the early dynasties many questions about the donation of votive offerings—and about private religious observance in general—must remain unanswered. We cannot be certain, but it is tempting to suggest that Early Dynastic local shrines were used by all members of a community, from the head-man down to the lowliest peasant.

Other books

Reye's Gold by Ruthie Robinson

Rogue (Book 2) (The Omega Group) by Andrea Domanski

A Soldier's Story by Blair, Iona

The Dragons of Argonath by Christopher Rowley

Falling for the Groomsman by Diane Alberts

Not What It Seems (Escape to Alaska Trilogy) by Sinclair, Brenda

A Dark Beginning: A China Dark Novel by Paula Hawkes

A Good School by Richard Yates

Final Score by Michelle Betham