Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History (65 page)

Read Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History Online

Authors: Robert Bucholz,Newton Key

We have already observed that Charles II had money problems. Despite what Parliament saw as a very generous financial package, he was constantly in debt. There were many reasons for this. First, Parliament refused to pay off his or his father’s obligations from before the Restoration: as a result, Charles II began his reign over £900,000 in the red. On the revenue side, a trade depression at the beginning of the reign reduced yield from the Customs and Excise. Soon after, London’s commerce was virtually paralyzed as the Great Plague (1665) and then the Great Fire (1666) laid waste to the metropolis. This was to be followed by a disastrous war against the Dutch (see below) which would raise the royal debts to about £2.5 million by the end of the decade. As always, the Crown was left with only two choices: reduce expenditure or raise revenue. The Treasury, which was becoming a fully-fledged bureaucracy, attempted financial retrenchments in 1662–3, 1667–9, and 1676–7. But all were undermined by rapacious courtiers pressuring the king to resume his spendthrift ways. Nor would Parliament raise the king’s revenue to fund mistresses and favorites or, worse, an army which might be used to reduce the liberties of the subject and impose a new religious policy on the nation.

Charles II’s religion was a matter of great anxiety to his subjects. During his formative years he had spent more time in the company of his Catholic mother than his Anglican father. Subsequently, he had been exiled in Catholic countries and courts. There, Roman Catholic splendor and pomp impressed him, prompting him to remark to the French ambassador that “no other creed matches so well with the absolute dignity of Kings.”

7

Nor could he have forgotten that, while Anglicans, Puritans, and Presbyterians had all questioned royal authority before and during the Civil Wars, some eventually working to kill his father, Catholics had either supported the Royalist cause unswervingly or had lived quiet, apolitical lives. He recalled with gratitude that he had been harbored by Catholics after his defeat at Worcester in 1651. What is not clear is how strongly Charles II felt this attraction to Catholicism. On the one hand, the king was never a particularly religious man and, knowing the strong anti-Catholic feelings of his subjects, he was far too cagey to admit such inclinations publicly. On the other, as we have seen, he recreated the fraught religious situation at his father’s court by marrying a Portuguese Catholic princess in 1662. Once again a Catholic queen of England worshipped in her Catholic chapel at St. James’s Palace, ministered to by Catholic priests and monks. Once again “Papists” were welcome at court. At least it appeared that the English people did not have to worry about Catholic heirs for, as the 1660s wore on, it became clear that Charles II and Catherine were unable to produce children. But just as this fact became obvious, so did another: the king’s brother and heir apparent, James, duke of York, was also inclined to “popery.” By 1670 he had probably converted secretly to Rome. A less subtle man than his brother, by 1673 he was shunning Anglican services. People began to wonder uneasily: would the next king be a Catholic?

Religious policy in England was always bound up with foreign policy. At the start of the reign, it appeared that the country had little to fear from its traditional external Catholic enemies, the Spanish and the French, because the Thirty Years’ War had exhausted them both. Rather, throughout the 1650s and 1660s England’s most important economic and military rival was the Dutch republic, the United Provinces of the Netherlands.

8

The Dutch possessed a commercial empire in North America and the Indian Ocean and the decay of Spanish power left them fighting with the English and French for dominance of world trade. The additional facts that the United Provinces was a republic which had frozen out Charles’s nephew, William, prince of Orange (1650–1702) from his traditional hereditary executive role as stadholder, and that Dutch Calvinist religion was theologically similar to Puritanism, did nothing to endear them to the new Anglican–Royalist regime. Rather, if one had asked a moderately conservative Englishman in the 1660s where lay the greatest danger to English liberties, he would have said with radical Dissenters at home and the Dutch republic abroad.

Parliament challenged the Dutch and their trading empire by renewing the Navigation Acts of 1650–1 in 1660 and passing the Staple Act in 1663. This legislation forbade foreign ships to trade with English colonies and required that certain goods shipped to and from those colonies pass through an English port. This, plus Stuart support for William of Orange, led to a second Anglo-Dutch War in 1664–7. The war began in North America in 1664, with the English taking New Amsterdam (renaming it New York). However, after a series of inconclusive naval battles in the Channel in which the duke of York, as lord high admiral, distinguished himself, the English laid up their fleet in 1667 in order to save money. This was a fatal mistake. It allowed the Dutch to sail unmolested up the Thames and Medway, burning the docks at Chatham and capturing English shipping, including the flagship of the Royal Navy, the

Royal Charles.

This humiliating defeat eventually led to peace with the Dutch, the fall and exile of Clarendon, and the rise of a group of courtier-politicians whose initials, taken together, conveniently formed the word “Cabal” (that is, a small coterie involved in intrigue): Thomas, afterwards Baron, Clifford (1630–73); Henry Bennet, earl of Arlington (1618–85); the duke of Buckingham; Anthony Ashley Cooper, Lord Ashley (1621–83); and John Maitland, duke of Lauderdale (1616–82). This group is sometimes seen as a precursor to the modern cabinet, for each member took on a particular ministry or responsibility: Clifford at the Treasury, Arlington focusing on foreign policy, etc. In fact, real power still lay with the king, who often withheld information from his ministers and played them off against each other. As this implies, the Cabal did not really operate as a team and felt little loyalty to each other. What they did have in common, besides their former opposition to Clarendon, was an inclination toward religious toleration (although for quite different groups) and a desire to increase royal power as well as their own.

One way to do all of those things was to reform the king’s government and retrench its vast expenditure so as to be less dependent on Parliament. There was a pressing need for such reform because the Second Dutch War had exposed naval and military inefficiency and corruption, added £1.5 million to the national debt, and depressed trade. This last caused the royal revenue to fall to about £650,000 a year – just over half of its intended yield. The new ministry established a Treasury Commission to centralize financial control in one office (the Treasury), to reform the collection of revenue, and to examine the minutest details of royal expenditure. Their short-term goal was to get the king out of debt; their long-term goal was to increase his power by saving him money and so decreasing his reliance on Parliament. Another way to do this was to gain the diplomatic and financial support of Louis XIV’s France.

The Declaration of Indulgence and the Third Dutch War, 1670–3

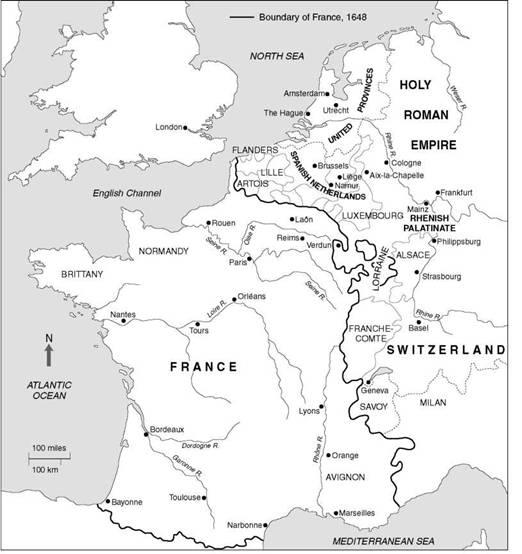

By the end of the 1660s, Louis XIV was, to most Protestant Europeans, the living embodiment of royal absolutism and intolerant Catholicism, much as Philip II had been a century previously. His Protestant critics accused the Sun King of intending a universal Catholic monarchy dominating all Europe. This was probably an exaggeration. At first, Louis’s likely goal was simply to establish France, in succession to a declining Spain, as Europe’s greatest economic, military, and colonial power. But gradually, that ambition evolved into a more specific and grander scheme: the absorption of the Spanish Empire. Since the sixteenth century, Spain had governed a vast expanse of territory that included the southern or Spanish Netherlands (what is today Belgium), Portugal (to 1641), much of Italy, most of Central and South America, and the Philippines (see

map 8

, p. 131). In the later seventeenth century, this empire was ruled by a sickly and mentally incompetent invalid, Carlos II (1661–1700; reigned 1665–1700). Since Carlos had proven himself incapable of having children, a new royal line would inherit his empire when he died. Louis’s position, bolstered by his marriage to a Spanish princess, was “Why not Louis?” The resulting combination of French military power and Spanish wealth would make the Sun King the master of Europe.

Obviously, Louis’s dream of uniting the two great Catholic powers was Protestant Europe’s worst nightmare. The Dutch republic, only recently free of Spanish domination, the sole continental Protestant state west of the Rhine, and a major trading rival of the French as well as the English, felt itself to be particularly vulnerable. When, in 1667, Louis’s armies swept into the Spanish Netherlands, the buffer zone between France and the Republic (see

map 12

), the Dutch hastily formed a Triple Alliance with Britain

9

and Sweden to force Louis back. The Sun King was infuriated to discover that the road to Spain lay, militarily and politically if not geographically, through the Netherlands. The resulting wars threatened the very existence of the United Provinces. Some in the Dutch republic advised capitulation; they were opposed by the stadholder from 1672, William of Orange. William was determined to save the Republic, prevent Louis’s absorption of the Spanish Empire, and preserve the liberties of Europe. To accomplish this, he sought a Grand Alliance of European states to balance the ambitions of the Sun King. Observing the situation across the Channel at the end of the 1660s, many English men and women came to feel that the real danger to their liberties came not from the Protestant Dutch republic but from a vast Catholic conspiracy aimed at a world-encircling monarchy headed by Louis’s France. Worse, they worried that a crypto-Catholic regime in London was aiding and abetting that conspiracy.

They were not far wrong. In 1669 Louis XIV, anxious to detach the British from the Dutch as a prelude to crushing the Republic, began to make discreet approaches to the English court through his sister-in-law, Henrietta Anne, duchess of Orléans (1644–70), who also happened to be Charles’s sister. The result was the Treaty of Dover of 1670. According to the public provisions of this treaty, Charles II’s British kingdoms would ally with France against the United Provinces in return for a payment of £225,000. Thus, each side got something it wanted. Louis broke the Anglo-Dutch alliance and acquired the use of the Royal Navy in the bargain. For Charles II, Louis’s subsidy meant that he would not have to ask parliamentary permission to raise an army. Freed from Parliament and possessed of an army, the king could pursue a new religious policy. And that was just the public side of the Treaty of Dover. According to a secret provision of the treaty known only to Charles, Arlington, and Clifford, the king had promised to convert publicly to Roman Catholicism. In return, Louis would supply an additional £150,000 and French troops should the Protestants in those kingdoms rebel. In other words, the Treaty of Dover was a risky attempt to solve the king’s constitutional, financial, religious, and military problems at one bold stroke.

Map 12

Western Europe in the age of Louis XIV.

What Charles intended by the secret provisions may never be known. Certainly he never attempted any public reconciliation with Rome. Some historians see the signing as a characteristic piece of duplicity, a promise of anything to get Louis to fork over the money. But Charles had to show some good faith on his side, and, in 1672, he acted. He proclaimed a

Declaration of Indulgence

which suspended penalties against both public Nonconformist and private Catholic worship. The king hoped that Dissenters would be so grateful to have their liberties restored that they would not mind similar liberties being extended to Catholics. In fact, many Dissenters and virtually all Anglicans seem to have felt that this was too high a price to pay. Local response to the 1672 Indulgence was generally negative: in at least one market town officials beat drums to drown out the voice of a Nonconformist preaching in the market place. To provide money for the war, the king also proclaimed the Stop of the Exchequer in 1671; that is, he suspended payment to those who had made loans to the government. This freed up funds to outfit the navy, but it also bankrupted a number of great merchant-financiers and ruined the Crown’s credit for years to come.

Worse, the Third Dutch War went badly for the Anglo-French alliance. Though the French army nearly overran the Republic, it was itself driven back when the Dutch opened the Atlantic dykes, flooding their own country in order to save it. In open water, Charles’s Royal Navy performed poorly against the Dutch. Moreover, this half-hearted effort proved to be far more expensive than Charles or his ministers had anticipated. As a result, in February 1673, the king was forced to recall an angry Cavalier Parliament. It was no more sympathetic to the Declaration of Indulgence than it had been to Charles’s previous calls for toleration. It rejected the Indulgence and instead passed the

Test Act

. The Test Act was an extension of the Cavalier Code. It required

all

officeholders to deny transubstantiation and to take communion in an Anglican service. Dissenting officeholders could accommodate themselves, with some difficulty, to the law by the practice of

occasional conformity

(that is, taking the sacrament upon entering office and then attending their own services the rest of the time). But no good Catholic could ever deny transubstantiation or accept Anglican communion. As a result, the new law “smoked out” many secret Papists in government, including the lord high admiral, James, duke of York, and the lord treasurer, Lord Clifford, who were forced to resign their places. The outing of James as a Papist shocked the nation, raising the specter of a Catholic plot to subvert the constitution at home just as the Stuarts were helping the Bourbons to liquidate the Protestant Dutch and absorb the Spanish Empire abroad. These fears and revelations doomed the French alliance and the Cabal. In order to secure any supply from Parliament at all, the king made peace with the Dutch in 1674 and dismissed most of his ministry. For the moment, the Dutch republic had been saved, though its war with the French would drag on and Louis’s later incursions into Franche-Comté, Luxembourg, Lorraine, and Orange in 1679–88 would tighten the noose. Thus ended Charles II’s boldest attempt to solve the problems of sovereignty, religion, foreign policy, and finance.