Eastern Inferno: The Journals of a German Panzerjäger on the Eastern Front, 1941-43 (2 page)

Read Eastern Inferno: The Journals of a German Panzerjäger on the Eastern Front, 1941-43 Online

Authors: Christine Alexander,Mason Kunze

Tags: #Bisac Code 1: HIS027100

While lacking the polish of later published personal accounts, Roth’s monograph has the advantage of being written as the events happened and not after the war, when memories can be muddled and remembrances altered by later experience. This is the strength of Roth’s work, as his thoughts are unaltered; the stark events recorded don’t undergo a metamorphosis to fit later sensibilities.

Hans Roth eventually disappeared into the cauldron that became known as the Destruction of Army Group Center. He undoubtedly was working on his fourth journal when he lost contact with his family in summer 1944. His three completed ones had been placed in safekeeping back home, with the last one ending in July 1943. Little is known of his service after that date, except what was included in letters home, but these did not cover the horrors of the war as his journals did. The location of Hans Roth’s grave is unknown.

However, the journals he kept provide a memorial for him and the millions of soldiers whose lives came to a horrific end in a war far from home.

J

EFFERY

W. R

OGERS

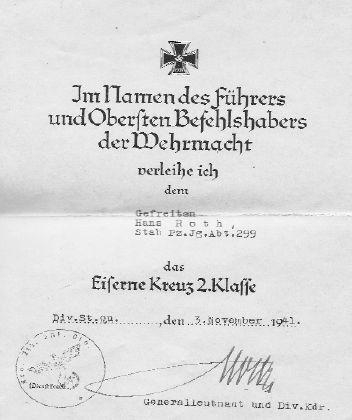

The Iron Cross, Second Class, awarded to Hans Roth on November 3, 1941, along with its accompanying certificate.

(Photos courtesy of Christine Alexander and Mason Kunze)

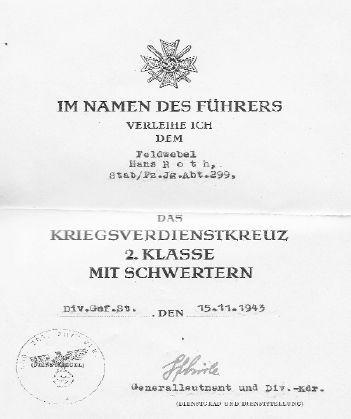

The War Merit Cross, 2nd Class, with Swords, awarded to then-Corporal (Feldwebel) Hans Roth on November 15, 1943, with certificate.

(Photos courtesy of Christine Alexander and Mason Kunze)

JOURNAL I

OPERATION BARBAROSSA AND THE BATTLE FOR KIEV

Editors’ Note:

In Hans Roth’s first journal, the 299th Infantry Division, in which he served under General Willi Mosel, is poised at the Bug River in Poland, waiting for the launch of Operation Barbarossa, Germany’s massive surprise attack on the Soviet Union. The division is part of Walter von Reichenau’s Sixth Army, which will comprise the left flank of Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt’s Army Group South.

The Germans had arrayed three army groups: North, with Leningrad as its ultimate objective; Center, aimed straight at Moscow; and South, with its first objective Kiev, and then the industrial regions beyond. Army Group North had one panzer group, which was assisted by the proximity of the Baltic Sea in cutting off Soviet forces. Army Group Center had two panzer groups deployed on each wing, which performed an impressive series of encirclement battles at Brest-Litovsk, Minsk, and Smolensk, propelling the Army Group halfway to Moscow within weeks.

The German high command underestimated the challenge for Army Group South, however, as it only had one panzer group, with a huge expanse of territory to cover and no natural obstacles against which to pin enemy concentrations. Further, the Soviet forces in the south, under Marshal Semen Budenny, were the largest of any sector, consisting of over a million men, not counting reserves. All across the front, the Germans were shocked by the numbers of artillery pieces, tanks, and planes the Soviets developed, which far exceeded pre-war estimates, as well as by the ferocity of Soviet resistance. This was especially true in the south.

The result was that while spectacular gains were quickly made by Army Groups North and Center, Army Group South found itself in a difficult, confrontational slog against Budenny’s forces. The First Panzer Group, under von Kleist, could not effect encirclements by itself, even as the vast expanse of the steppe diluted its fighting strength. The initial stage of Operation Barbarossa in the south relied primarily on infantry divisions, which forged gradually across the territory, snowballing numerically superior Soviet forces before them until finally arriving before Kiev, where scenes reminiscent of the trenches of World War I were reprised.

Reichenau’s Sixth Army was the primary instrument of the advance, until in July the high command decided to employ the panzers, along with Seventeenth Army, in a subsidiary encirclement battle against a Soviet salient at Uman. Successfully completed on August 8, with the capture of over 100,000 prisoners, this truncation of Budenny’s forces opened the door to further advances near the lower Dniepr and the Black Sea, including the entranceway to the Crimea.

Meantime, Sixth Army had fought its way through Korosten, Zhitomir and other towns to the outskirts of Kiev, where it found itself in a veritable death-grip with the Soviets’ Southwest Front, which was considerably larger in both men and firepower. While most accounts of the onset of Barbarossa describe spectacular advances by the German panzer divisions, Roth describes the pure hell undergone by the infantry divisions of Sixth Army, as they waited for their high command to devise a solution to their original miscalculation.

In the journals that follow, which were translated from the hand written versions, occasional punctuation and paragraph breaks have been added for clarity. For certain idioms or technical references, explanations have been added [in brackets] where possible. The titles assigned to the journals themselves are the editors’ and were not part of the originals.

Gefreiter (Private) Hans Roth.

(Photo courtesy of Christine Alexander and Mason Kunze)

[ON THE JOURNAL’S FIRST PAGE]

Once again we are close to being deployed on another difficult assignment. I am hoping that what follows will become my diary. In it, I will recount the daily events just as they occur, without any embellishment. I am still not permitted to write such things to my wife, but will tell her later.