Eastern Inferno: The Journals of a German Panzerjäger on the Eastern Front, 1941-43 (6 page)

Read Eastern Inferno: The Journals of a German Panzerjäger on the Eastern Front, 1941-43 Online

Authors: Christine Alexander,Mason Kunze

Tags: #Bisac Code 1: HIS027100

Under the cover of our cannons, we draw closer to the tanks that are still standing, and which are still firing like crazy. The second wave approaches, and there on top of the hill one can already see the third wave. We must retreat, as we are under heavy fire. One after the other, we work our way back from one trench to the next. My comrade on the left throws his arms in the air—he’s been hit. The cannon that was protecting us suddenly breaks apart—a direct hit. A comrade lies motionless on the ground right in front of me—dead; and to my right a soldier is also shouting for the medic.

Just twenty meters to the trench! Please God, help! Will this be the end? They are now shooting shells right in front of our feet. I throw myself down on the ground and hold on to the earth. The ground is being ripped up right before me. I jump up once again, almost stumbling over two comrades who have been torn apart from the shelling. Damn tank cannons! Another impact right in front of me! The shrapnel is howling around my ears. A fist-size chunk shreds my gas mask; more shrapnel severs the hand piece from my machine gun.

And then, I finally make it! I am now in the trench. I suddenly do not care anymore. I throw myself on the ground, face to the sky, and wait for the tanks to arrive and crush me.

Poor Rosel, sweet Erika!… Your husband fell on the field of honor on 3 July… etc., etc.… Don’t think, do not think!

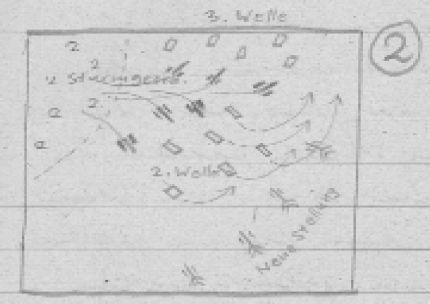

Meanwhile, the following happened in our section: the accurate fire of our cannons fought off the first attack, and our anti-tank cannons took advantage of the chaos that followed to change their positions. The second wave pushes wild firing toward our previous positions in an attempt to crush us. Suddenly, they receive fire into their flanks from the east. A few heavy tanks are eliminated. They turn immediately to the east and take our current position under fire.

[Side note:] This saves my life. Apart from myself, there was no one else at our former position. Two men succeeded in making it into the woods to the west. The remaining men were lying in the field either dead or wounded.

Moments later, the third wave approaches from the hill, and at the same time, our assault guns advance, firing in turn at the second and third waves.

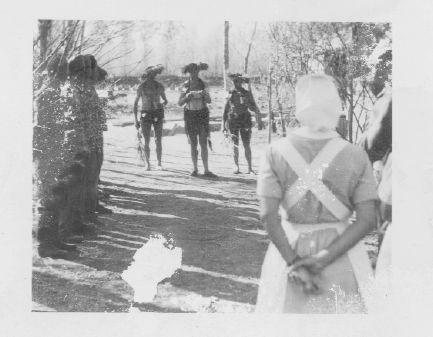

Photograph taken by an unknown German soldier on 14 September, 1942 in the village of Onufriyvka close to Kremenchuk in present day Kirovohrad Oblast. A group of German soldiers are being awarded the “Eiserne Kreuz”—the Iron Cross. (Photograph courtesy of Håkan Henriksson)

This situation may be unique to the entire Eastern campaign. The leaders know that only this move alone will be able to save us from destruction. Remaining cool-blooded is the key to success in such circumstances. One imprecise shot can hit our own assault guns and vice-versa; inaccurate fire from our anti-tank cannons can destroy our own assault guns.

Being fired at from two sides, the second wave veers to the north, creating havoc for the third wave. Sixteen more Red tanks are destroyed and the rest attempt to take cover on the side of the hill.

And then a miracle happens: German SS troops in camouflage jackets appear to our rear. It is the

Leibstandarte

[

Adolf Hitler

]—finally arriving after hours of waiting. They were halted somewhere around Dubno and ordered on a forced march to come to our aid. They had only been in their positions for about ten minutes before alternating rows of Russian tanks and soldiers appeared. The battle lasted three hours. It was a terrible butchery—a man-against-man fight that could not have been any worse.

Photograph depicting German soldiers returning from a reconnaissance mission. As Roth describes, the men have camouflaged their helmets with reed and covered their bodies in mud. Taken in June 1943, close to Nikopol, present day Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, Ukraine. (Photograph courtesy of Håkan Henriksson)

A bayonet wounds my upper arm. Get the first-aid kit and move on! The sun is burning down on our helmets. I am no longer wearing my jacket. To their surprise, we attack enemy tanks and soldiers, who are dressed in just their shirts and pants. Aircraft arrive and join in on the ground attack with great effect. The entire valley is stirring like a cauldron.

Victory comes that afternoon. The Reds attack for the last time around 1500 hours. The masses charge with a loud “hurrah!” There are no longer any tanks; with our concentrated fire we mowed them down row after row. The attack is gloriously crushed. The Russians make a final retreat to the north.

As sweet as victory may be, our casualties are numerous. Of the 12 ordnances in the 3rd, seven have been destroyed by direct hits. My knees are soft like rubber. Don’t collapse! Although our strength is fading, there is no time to rest. That same night we march on to Rowne.

4 July:

Around midnight we stop at a village lying peacefully blanketed in the moonlight. We have not had any enemy contact until here. The plan is to stay here the rest of the night and sleep in the houses. However, we receive warning to move on, as the village may or may not be held by the Russians. Once again, we “rest” in the ditch next to the road. After making several detours, we arrive at our destination at around 0700 hours. We are refreshed after a few hours sleep.

The Russians have retreated a great distance. The division’s order of the day is read that afternoon. It is full of praise for our troops’ courage during yesterday’s tank battle. However, we also receive bad news: 36 comrades fell and many were wounded. The announcement ends on a staggering note: Red motorized units ambushed a supply convoy and annihilated it—53 comrades were butchered. Unfortunately, three of our own panzers arrived on scene too late. Michen, Hufmann, Brosig, Sudback, and Schmidt from our unit died yesterday.

5 July:

We continue our march in the morning. Our panzers took Rowne last night and we push forward in a forced march to cleanse the area like any infantry would. The heat is terrible! Our infantry marches in this heat 150km in two days. All the units are working tremendously hard.

6 July:

We continue on after midnight. Our pace is extreme; we barely have time to eat and we don’t dare think of sleeping. We break through the lines of a few weak enemy forces that are attempting to stand in our way. We leave their destruction to the troops that follow to our rear.

“Push forward! It’s all or nothing!” Damn it, what is “all” anyway! What is going on?

During the sparse breaks, we shuffle about on our legs of rubber. The sun is burning mercilessly on our skulls. The engines are humming quietly and radiate the stench of diesel. The dust is so thick that I am unable to see the person in front of me. My eyes tear up and burn. My mug [

fresse

, or face] is crusted with dirt. The damn limestone gets in everywhere.

We reach Korcecz at night. We pass through the town after a short battle. We roll on at a maddening speed. Orders to halt are finally issued after an hour. I feel like I was just put through a meat grinder. I let myself collapse a few steps from my motorcycle. Even the enticing smell coming from the mobile field kitchen is unable to motivate me to get up. Sleep, I just want to sleep!

7 July:

Our artillery fires all throughout the night. I think there is danger brewing out on the front lines. The air is thick and I can smell trouble. Rumors are circulating that we are in proximity to the dreaded Stalin Line.

In the early hours of the morning, strings of Russian fighters appear at low altitude. Their on-board machine guns scour our positions, and bomb after bomb is dropped across our lines. Thank goodness there are no casualties.

It calms down around noon—and how about that—we receive mail! After 14 days, a letter from Rosel. I am so happy to have that woman as my wife! Her bravery can be felt in each line. Her good heart gives me much courage and comfort for the difficult hours to come!

I have only one wish: to get home in good health and to thank her.

8 July:

Scheisse

. No sleep again last night. At around 2300 hours, our old reconnaissance group crept forward through the swamps around the Slucz River. We must have looked ridiculous with our painted war faces. On top of our heads we had our

hurratute

[slang for steel helmet] camouflaged with dirt and garnished with reed. We carried a bag with hand grenades around our chest and our machine gun over our shoulders. Our only clothing was a bathing suit. Our bodies were covered in clay from head to toe. That was how we left camp.

We made it to the first line of enemy bunkers without seeing any infantry or trenches. We returned around 0200 hours without ever being noticed by the Russians. I tried to sleep, though with no luck, due to the thousands of disgusting mosquitoes from the swamps that torture us down to the blood. It can drive one crazy! All of that on top of the heat and constant thirst!

Unexpectedly, at 1100 hours a swift attack from the Stalin Line. At the same time, Russian bombers attack at low altitude. We are suddenly awoken from our slumber. The first salvo was alarmingly precise. Wounded soldiers are crying and moaning. Foul-smelling smoke hangs below the trees. Ten minutes later, and the ground near us bursts into the air; fragments of splinters fly into our foxholes. The firewall moves slowly toward the so-called “Tarn Position.” Here, shells and bombs create a dreadful bloodbath; 41 dead and 82 wounded lie where our

Kradschützen

[motorcycle infantry] had been positioned. We have to work until late in the evening in order to recover the dead and secure our wounded comrades. My heart aches when I think of their loved ones—their mothers, wives, and children.

We regroup and reposition on the same night due to the large number of casualties. The grand attack against the front lines and the fortifications to the west of Zwiahel [Novohrad-Volynskyi] will commence tomorrow morning. The situation is as follows:

Our scouts discovered days ago that 5th Army is moving in a forced march toward Zwiahel so as to secure an important crossing over the Slucz River. The crossings are being protected by strong enemy units. However, thanks to our forced march, we have arrived here first. I now understand the reason why we were marching at such an insane speed during these past few days. The primary Red Army formations are still a day’s march to the east of Zwiahel. We must use all our strength to break through the strongholds so as to take the city and river crossings tomorrow. Each and every one of us knows what is at stake. We are ready.

9 July:

The big coup was a success. Today, around noon, the town of Zwiahel, and the crossings over the Slucz fell into our hands after fierce resistance—just in time. The initial units of the Russian 5th Army arrived at just about the same time. We could not have asked for anything better than to have the band of fortifications now destroyed. The effect of our 30.5 caliber mortars and Stukas was devastating. Together with the

Sturmpioneren

, we contributed well to the collapse of the bunkers.