Eastern Inferno: The Journals of a German Panzerjäger on the Eastern Front, 1941-43 (28 page)

Read Eastern Inferno: The Journals of a German Panzerjäger on the Eastern Front, 1941-43 Online

Authors: Christine Alexander,Mason Kunze

Tags: #Bisac Code 1: HIS027100

There is one statement that all four of them have made: this is supposed to be their first substantial undertaking, and the explosion isn’t expected to occur for two months. (These guys were right; on October 5, a section 200 meters north of us is blown up.)

For days, trouble has been in the air. Nobody is thinking about going on leave or nice things like this anymore—we just don’t have the time for it. Early today at dawn, this week’s 14th Soviet tank assault rolled in. Now in the late afternoon, it has finally been pushed back. We closed in on them with tanks and FlaKs, and broke through their lines all the way to a small section of forest. It was very difficult this time. We did it though, and a deep drag on a pipe is our reward.

On the front line, the infantry is waging a stubbornly hard fight. On a hill across the way, where the rubble of a large tank is, where the ground has been turned over a dozen times by shells, where burned tree stumps stand strangely sad against the sunny sky, all hell seems to have broken loose. Our mortars send blasts that ignite fireworks of red lightning bolts onto the ridge, which creates a thick wall of smoke. And since their tanks were snubbed, the Reds are now sending bombers and low-flying anti-tank bombers which mess with the ground combat. Our machine guns are barking, and our grenades hiss as they fly across to the enemy. The droning of airplane engines and the rattling of on-board weapons mix together into an infernal noise, which fills heaven and earth.

There is suddenly a strange tone to the uproar, a tone that sharpens our ears and heightens our senses: enemy artillery! The rounds are crashing about while tired fragments, the late comers, which fall out of the sky with a final mean snarl, splash onto the wooden planks of the trench covers.

They are shooting poorly today, the Reds. They must know it as well, for after the fourth round, there is silence. The front line is growing quiet as well. I am familiar with this; for one hour there will be peace and quiet, only to start up again with full force when night falls, and early tomorrow morning, when the

schweine

come out again with their tanks. Just as a side note—I want to go on leave. It brings tears to my eyes that I can’t tear myself away from here tonight. To go on vacation, especially now, seems so incredibly remote!

10 August:

I am on the train home, which moves along bumpily, as slow as a snail. It is almost unbelievable, but nonetheless, I am sitting on board a solidly built German passenger train. Each passing telegraph pole brings me closer to seeing my dear Rosel and my little girl again. Luckily the trip is long, because it is difficult for me to leave behind the experiences of the last hours on the front line. It was hard to leave; two of my men fell. The gun-carriage burned out; all my stuff has gone to the dogs.

It’s best to sleep; in sleep lies oblivion. Perhaps it will also bring nice dreams, an advance on the happy days ahead of me. What a lucky dog! I am getting teary eyed—now that’s unbelievable! Who could understand what is going on inside of me?! A lucky dog isn’t supposed to be sad!

6 September:

I am back with my unit! The seventeen days of sun and happiness lie behind me like a distant dream. It was an entirely great experience, this leave. Full of gratitude, I think of my love, whom I have to thank for the countless hours of untroubled happiness. Unforgettable will also be my hours with little Erika. Everything, really everything, was full of harmony and sunshine. I have many beautiful, comforting thoughts and memories stored up for the approaching difficult winter days. I received so much new energy and optimism from my time at home. Everything makes sense again. To cherish something like this, and to fight for it, is worth it. Yes indeed, it is worth it!

“

Sakra

! [Damn!],” one of our Bavarians spouts out behind me. That’s all he says. There is a deadly silence now. Oh how it’s blowing outside. Chalk and mortar dust rain down on us like droplets of flour from the ongoing fire from above. Good old stone ceiling, please hold up and don’t let us down!

Orders are supposed to be picked up at regiment HQ this afternoon. I volunteer for this because I can’t stand anymore the stifling air that has been depleted of oxygen, nor the torture of stiff bones and numb limbs. How wonderful the fresh air is! It has stopped raining and a humid haze fills the streets, through which the ghostly grey and sad ruins stick out. The fire has died down. Only occasionally does a volley pass over the high buildings. The whining 122s explode with a dull sound. The street is nothing but a mud hole, and thick mud splatters with every step since the gutters are buried under mountains of rubble. The sun is coming out, but I have no time to enjoy it, because at this very moment the bombing is starting up again with full force. Artillery fire rages over the ruins like rain showers. This damn muck won’t allow me to run. I have to cross some backyard where it is worse. I’m hoping I don’t trip—dear God, don’t let me fall in this manure. The stench from dead bodies is penetrating my nose, and I can’t breathe enough fresh air. This sloshing and sliding through the sticky muck seems endless. Over head, there are sounds of planes, and all around the crashing of bombs. There are many blind shells that sink into the mud. Off to the side is the glistening body of a Rata with grey-green wings, which show off the carefully painted Red Soviet star.

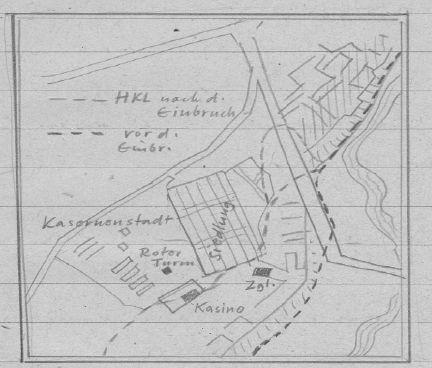

A sketch by Hans Roth showing the center of Woronesh (Voronezh), including the Germans’ main line of defense (HKL) and forward positions.

Verdammt

[damn], I should already be there! There is the main street, which isn’t a street anymore, devastated by constant bombing. My map still shows the rows of houses, which have long since been ground to a pulp by shells. Further ahead, where “

Molotov-Platz

” [“Molotov Square”] must be, there is apparently mortar fire; one can hear its barking like a pack of mad dogs. Single shots whiz by at close range with a dull swash.

It’s no use. I’m sweating like a monkey [

ich schwitze wie ein affe

], my knees are weak, and I need a cigarette break. Volleys of heavy shells are sweeping over my head in the direction of “

Rote Fabrik

” [“Red Factory”]. Their impacts are not too far away, though not far enough to be protected from their noise and close enough to observe them. A torn up patch of oak trees is cloaked in smoke. Right now, a giant tree trunk is being blown to pieces, with splinters flying all over the place. There is a blind shell from which I crouch down close to a wall. And across the way, more craters are being formed; smoke plumes trail into the air and clods of dirt are being tossed everywhere. Right now a piece of shrapnel explodes with a loud bang; white-grey clouds of smoke and glaring lightning flashes fill the entire street. I stare at this horrific scene, spellbound.

Then, all of a sudden those

hunde

[dogs] start to aim more closely. A burned up projectile hisses as it drowns in the mud. I didn’t notice that I had placed my hand over my mouth. There is a loud howling. My God they are huge! Just barely do I reach a partly collapsed basement before the storm begins. A rumbling vibration penetrates the ground all the way to where I am located. What started as a cigarette break has now turned into a long hour of fear and terror.

It’s Sunday, and also a sunny day. After the cold and rainy days, it has finally started to feel like May since yesterday. The sky above the ruins of the big city of Woronesh is blue and peaceful. I climbed all the way to the top of the vast ruins of the gun-powder factory, and am now crouching among the molten and bent iron beams of the ceiling. It is a great view from up here; you can see about a third of the entire city. Over there flows the Woronesh, that good old river, with its wide, muddy streambed, which has been a good front for us for weeks, and also a good barrier to the advancing Reds.

One has been able to let his guards down during these August days, even the command. Our trust in the muddy flow of the good old Woronesh has turned into an inexcusable recklessness. Night after night, we notice that the Russians have started piling up huge amounts of stones. Message after message was sent to the division. Air reconnaissance reported that tanks have been assembled in Mona styrtschenko. Except for a few shells, nothing, absolutely nothing, has been done to guard against this encroaching disaster. One fine day the stone dam across the Woronesh was actually finished. Multiple messages were sent to command. Their answer was as follows: “Let the tanks come close, that way they will be easier to shoot down.” Excuse me for not recounting the details of how well we did in shooting down their tanks.

16 September:

The Russians have gained control of the eastern slope of the southern part of Woronesh. Along with it, we lose the important defense bastions of “casino” and “brick yard,” which provide the enemy with a view of the entire hinterland. They are even able to see as far as the Don, with its hills and supply roads. I have already been told how unsuccessful and bloody the counterattack has been, and how the weeklong bombing from hundreds of weapons had no effect.

Ever since then, the Reds have been sitting in the “casino”—an enormous pile of rubble where the basements are deep and safe. They have also been sitting in the oven of the “brick yard,” which could not be easily destroyed by our Stukas. All this looks like a yellow-brown burned out patch lying there harmlessly in the sunlight.

To the north and the west, as far as you can see, is an ocean of bombed out houses—nothing but a gigantic field of ruins. Smoke is rising from it in all shades of grey. There are also the white and yellow clouds from the new fires, which mix with the violet and grey fog of the smoldering and dying fires. Towering, threatening over them are the monumental stone and concrete fortresses of the Party, the Soviet castles. They had been fortified, and every single one of these buildings has seen bitter fighting; each one has its own bloody history. Whoever fought in Woronesh will forever remember one particular bloody battle for a block of houses, the “Operation Hospital.”

There is “Red Square,” with the ostentatious Soviet government building; on its façade you could still see a row of small torn-up red flags. Then there is the prison, a huge building with walls more than a meter thick, which even our heaviest guns could only slightly scratch. One side of the building was blown up at the last minute by the Bolsheviks prior to their retreat. Judging by the smell, there must be buried under the ruins a whole mountain of corpses. To the north and northwest is the industrial sector of the town. All the way to the horizon one sees factory after factory, blast furnaces, and steel mills. The engineering works “

Komintern

,” which used to have 10,000 workers, is now nothing but a pile of iron and bricks. Then there is the “

Elektrosignal

” factory, which employed 15,000 workers, and the “

Dershinsky

” factory, where each month 100 to 120 locomotives were built. Further to the west stand the sad, black skeletons of the huge burned out airplane hangars. Next to them are the airplane factories, which as you can imagine were gigantic, particularly when you read that 40,000 people used to work there. I could go on and on….

To the south are the straight, square blocks of barracks, which can’t be seen at the moment because the smoke from the drumfire is hanging over these cement quarters. Again there is the “Red Tower,” partially covered by the dirty yellow plumes of smoke from the gun powder. Everywhere, for as far as the eye can see are ruins and more ruins! The once booming city, with its 450,000 inhabitants, is now a dead city, reigned by terror and death. And yet, it was still worth taking this city, despite the great sacrifices, and to defend it despite the even higher number of casualties. This was the cardinal point and pillar of the front, which had to cover the deployment and attack of the southern armies. Here in particular lies the prerequisite for the success of the operations against Stalingrad and the Caucasus. Stalin, who is well aware of this, is deploying rifle division after rifle division and tank brigade after tank brigade. His goal is to break down this diversionary front. Up until now, we have been able to withstand his enormous pressure, and will continue to do so no matter what happens!

Mangled cables are hanging from the telegraph posts. Swarms of flies buzz over the cadavers of dead horses, which are lying everywhere. One could write volumes about this plague of flies, these shimmering blue-green pests. The penetrating stench of the cadavers attacks one’s senses relentlessly, but our nose and eyes are already used to this symphony coming from the ghostly city. The one thing that we are unable to get used to though, is the nasty flies. They are drawn to all the dying corpses under the rubble, and have multiplied to form large swarms too countless to grasp. Birds are also circling over the battlefield; thousands of crows screech above the ruins and fields of death. Again and again, they dive into the depths of the rubble when they see the horrific harvest of death.