Eastern Inferno: The Journals of a German Panzerjäger on the Eastern Front, 1941-43 (26 page)

Read Eastern Inferno: The Journals of a German Panzerjäger on the Eastern Front, 1941-43 Online

Authors: Christine Alexander,Mason Kunze

Tags: #Bisac Code 1: HIS027100

The fight lasted no longer than two minutes, by the time the fighter had already disappeared. The sky is blue and cloudless, just as peaceful as it was before. Even the split pea soup in our bowls stayed warm—that’s how quickly it happened.

30 March:

Totally unexpected, the weather has changed overnight. A blizzard rages with a strength that we have not encountered all winter. I pity the sleigh units who were surprised by it in the open field. Our eyes are unable to penetrate more than two meters into this crazy flurry. In front of us are two enroute sleigh units; we are very worried about them, as they are several hours late. Only by the evening does one of the vehicles arrive; there is no trace of the second one.

31 March:

The storm has subsided. The sun hangs in the sky peacefully, as if nothing has happened. And yet, a lot has happened overnight. In yesterday’s blizzard, the second sleigh unit missed the road and fell into a deep gorge; our comrades froze to death during the night. And something else, even more serious, has happened: with the heavy eastern storm to their backs, the Reds have once again succeeded in blocking the highway near Drosty. In order to boost the counterattack, we reach the breakthrough point by around noon.

The enemy’s power has already been broken; there is not much more for us to do here. Our artillery has wreaked havoc in Drosty, which had been occupied by the Reds for a few hours. The beaten enemy had to leave hundreds of dead people behind. It is looking particularly gruesome on one of the village streets. Someone calls it the “avenue of death.” Others pick up the phrase, write it on a board, and attach it to a pole on the side of the road—Avenue of Death! Until the war ends, this part of Kursker Street will be named this.

To the left, in a ditch, lies a dead female gunner; the artillery has mutilated her badly. One half of her still young face is completely missing. Her long, blond hair is hardly able to cover the terrible wound. If her grey-brown shirt had not been ripped open across her chest, I would not have known that a woman’s fate had ended here.

It is a strange sight for a soldier, who is only used to fighting against men, then to suddenly be confronted with the dead body of a woman. Occasionally there is a woman among the prisoners. Among them are bad, ugly bitches whose thirst for blood and brutality does not fall short compared to those of their male counterparts in the Soviet Army. Mostly women and young girls, who have been pushed by Bolshevik pressure and instigation, leave a final reminder of their female dignity behind and dabble in the craft of men, with a gun in their hand.

1 April:

A security mission calls us to Medwewskoje. This is also the temporary gathering point for what remains of the 299th Infantry Division and other units, which had been assigned to different groups. In terms of formation, we are commencing the “cleansing” of the front. Within a few weeks we will track to the north in the direction of Kursk and will be once again be under the trusted leadership of General Moser. Spring cleaning has also arrived on the front!

Mid-April:

It’s the muddy season!

Roads and streets, which were frozen solid only a few days prior, have now thawed and become bogs which threaten both men and animals with drowning. In many sections of our position there is nothing but dirty ice water for kilometers; during these weeks, on nearly a daily basis, we have to wade up to our chests through icy water in order to reach the staging ground of our attack with the enemy.

By the end of the month, I am ordered to undertake an important courier mission to Orel and Charkow. It would fill every page of this book alone to retell what we encountered there enroute with the partisans and the dangers on the roads, which are mostly submerged in water.

In Charkow, we happen to get caught in a tank battle, and in Bjelgorod, a heavy Russian attack blows up our store of ammunition—it’s a miracle that we have come out alive. Before Kursk, we are hunted down by Ratas, and my sidecar is riddled with machine gun fire; near Ponyri, a group of partisans try to capture us. In other words, we are glad as hell to be able to return to our group twelve days later.

By the end of April, the division is pulled from combat. We reach Kursk via an overland march, as the roads are impassable. We continue to the north, and two days later reach the main railroad hub of Ponyri. We take up quarters in Beresowiz. We are in the area of 2nd Panzer Army, and after the odyssey of the past winter months, we are finally able to return to Group Moser. Those wonderful days of rest suddenly come to an end on May 15. In a rapid forced march, we are thrown to the southeast of Orel, into the very dangerous Liwny sector.

25 May:

Forgotten are the winter and the muddy season—a stifling heat now hangs over our positions. Summer, with its scorching temperatures, has arrived almost overnight. Both the weather and the fighting are hot in this goddamned sector. Let’s hope that these are the final weeks of trench warfare, and that soon we will move forward again.

These brief summer months will soon be over and then, yes, perhaps then, there will be for us an unfathomable event—a reunion with wife and child, with father and mother.

May God grant us the chance to see our home once again.

JOURNAL III

FRONTLINE WARFARE AND THE RETREAT AFTER STALINGRAD

Editors’ Note:

As Hans Roth’s third journal begins he’s in the Livny (Liwny) sector, east of Orel, at nearly the farthest reach of the German front in Russia. Here he experiences trench warfare, as each side trades attacks and bombardments, and the Soviets attempt mining operations beneath the German fortifications.

In the meantime the great German summer offensive of 1942 commences, with drives on Stalingrad and the Caucasus. At first the offensive is highly successful, conquering hundreds of kilometers of additional territory. Roth goes on leave during August, but by the time he returns to Russia the German momentum has stalled. In fact, the Soviets are launching counterattacks all across the front. Woronesh (Voronezh), one of the first German objectives of the campaign, becomes the scene of bloody urban fighting.

On November 19, the Soviets launch a gigantic counteroffensive that caves in the German-allied fronts on either side of Stalingrad, isolating Sixth Army. Roth’s unit, which is outside the pocket, is dispatched to help bolster the Italian-held sector of the front along the Don River, but is helpless to prevent its utter collapse.

Roth’s battalion is then dispatched to Kursk, only to find Soviets closing in on the town and the Germans preparing to abandon it. City after city falls to the Soviet advance, and Roth finds himself marching halfway back to Kiev. Reflecting the fact that his

Panzer jäger

unit was once again employed as a mobile fire brigade, Roth not only expresses homesickness for his family but for the rest of the 299th Division, saying, “We heard that they fought gallantly.” During this period the journal largely foregoes exact dates, and when his unit is transferred to Orel aboard flatcars in mid-winter, his description is only of “endless misery.”

Despite intense combat around Orel, which is now part of a German salient bulging into Soviet territory, Roth manages to survive his second winter in Russia—one in which Sixth Army is utterly destroyed—and witness a new build-up of German forces. In the war to date, the Soviets had succeeded in the winter, whereas they had not yet been able to stop the Germans during good weather. The summer of 1943 would put this system to one last test.

June:

Before me is a vast Russian plain, massive gorges cut treacherously deep into the black earth, like cracks in a windowpane. Forever humid and swampy, they are a threatening breeding ground for malaria and other feverish epidemics which are yet to be named. The HKL [

Hauptkampflinie

—main line of battle] extends here along a thin strip of woods and sparse huts. The ground has been scarred and the grass scorched by thousands of impacts from the months of dug-in fighting. A tropical heat hovers over the badly torn up trenches. On the other side in this flickering heat can be found the Russian bunkers. It’s very difficult to keep your eyes open, for the heat is heavy and our limbs are like lead.

The half hour before noon, with its tempting calmness, is the most critical moment of the entire day. We wait for the meal service as we doze off, only a breath away from falling asleep. Then, all of a sudden, a hissing comes across from the other side, crashing with a thunder beyond our cover. The same thing occurs every day at noon. Regardless, we’re still startled from our dreams every time. The images of home and all our longing thoughts are abruptly torn apart….

The hissing, rolling, and thundering last for one to two hours. Here and on the other side, the relentless wind mixes the stinking plumes of smoke from the explosions, these waves of fumes in all colors, with the blinding white shrapnel clouds, into a dirty grey mass. The firewall begins to die down slowly.

The nights are damp and cold, and full of restlessness. After the artillery fireworks every evening to honor the departing day, the action increases on the front. The heavy artillery has been put to rest, and now it’s time for the small guns, for the PaKs, MGs, and carbines. On the front line, late-arriving troops fumble through the darkness. Glaring white flares hiss in the night sky. Like startled hens,

maxims

[automatic machine guns] are firing off somewhere in the distance. We respond by adding more machine guns, and within a few minutes, the whole chicken coop is in a great flurry, a hellish racket throughout the sector. It often takes hours before friend and enemy calm down; most of the time the night is over by then, and once again you have to forget about getting any sleep.

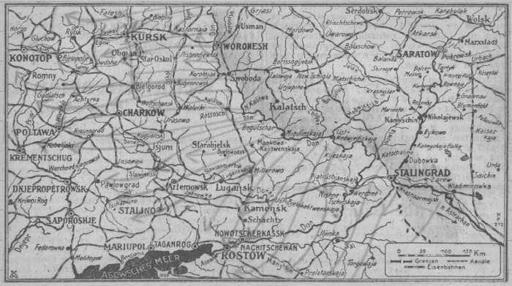

Map in Hans Roth’s third journal of the southern front during the massive Soviet counteroffensive at the end of 1942. The lines drawn in pencil apparently indicate the multiple enemy thrusts that cut behind Sixth Army, which found itself isolated in Stalingrad.

The air raids during these starry nights in the Liwny sector are unforgettable. An overwhelming calm after the evening’s infernal noise of dueling artilleries, a few quiet minutes when you can write a letter in the trench, then, all of a sudden, a fine singing in the air: the

Ivans

[German slang for Russian soldiers] are coming!

The light singing transforms into a rattling howl, which now fills the air for hours. Each night is the same awe-inspiring picture; hundreds of lightning flashes burst into the air. Shades of white, green, and red splatter the sky; long yellow-orange streaks shoot into the air, and are accompanied by the hard knocking of 2cm anti-aircraft artillery. Glaring white magnesium flashes then fall from above. Red flames from a fire sizzling on the ground jump out 50 to 60 meters, and then appear as yellow-white ornaments on a burning Christmas tree, which is what we call the American tracer shells—only there are no gifts under it, but rather infantrymen.