Edie (38 page)

Authors: Jean Stein

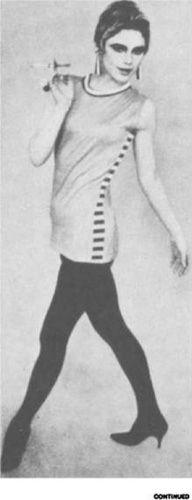

This cropped-mop girl with the eloquent legs is doing more for black tights than anybody since Hamlet. She is Edie Sedgwick, a 22-year-old New York socialite, great-granddaughter of the founder of Groton and currently the “superstar

1

’ of Andy Warhol’s underground movies. She used to wear her tights with only a T-shirt for a top but lately has taken to wearing them Kith mid-thigh-length dresses—”the simplest, stretchiest ones I can find.” Her style may not be for everybody, but its spirited wackiness is just right for lively girls with legs like Edie’s.

A

favorite outfit of Edie’s last summer combined her black tights with a white-banded T-shirt and floppy that

Life

fashion layout, November, 1965

RENÉ RICARD

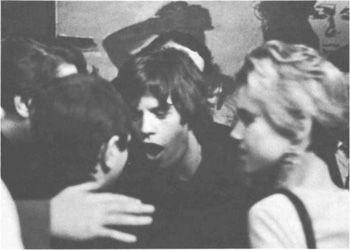

I was one of Edie’s escorts the night the limousines pulled up to The Scene, where she met Mick Jagger. I was there, and you don’t know how I felt, seventeen years old. It was an extraordinary moment! Edie Sedgwick, the most famous girl in New York, and Mick Jagger, the most famous singer and the one everybody wanted to fuck I And there he was.

We were at least two hours late at The Scene. Edie was always brilliantly late; Andy would wait for her; he’d never say a word. He trusted her aristocratic instincts. He always said, “She knows what she’s doing.” When she’d arrive, it would always be when the tension was at its greatest. Everyone at The Scene was saying, “Edie’s going to meet Mick. If s Mick and Edie . . . New York’s big girl and England’s big boy, and they’re going to be together.”

Edie was wearing the Gernreich dress she had modeled somewhere—breathtaking and in such great style—made of a cinnamon-colored, satiny football jersey. Her sleeves were pushed up and she wore a million bangle bracelets and very high, high heels. Earrings. We went down the stairs. Edie never, never carried anything when she went out on these evenings; I don’t even remember a coat.

It was in front of the coat-check place that it happened. Mick Jagger was there and Edie was there, facing each other. She said, “How do you do? I just love your records.” Well, what

do

you say? And he said, “Oh, thank you.” Then, all of a sudden, there was an explosion of people and every corner of The Scene emptied into the tiny vestibule where we were standing. People were pushing and banging up against each other. The flashbulbs were blinding. Edie was able to get to the ladies’ room. The poor thing! She was appalled by the crush. I don’t remember what happened the rest of the night. All I know is that the picture of the two of them standing together in The Scene, the dingiest and most disgusting place in the world, is imprinted on my retina because it was so glamorous

JOHN ANTHONY WALKER

I saw very little of Edie when she was in New York. I remember the irritation of once trying to phone her when she was at the top of the crest and being answered by a social secretary. Crazy, hard, tough chickie, I guess, in an iron-gray suit. I don’t know what she had on, obviously, being at the other end of the line, but that was my speculation. I was angry because she kept saying, “Miss Sedgwick.” Edie was not Miss Sedgwick . . . ever! I didn’t want to make an appointment with a Miss Sedgwick, so I didn’t.

ETHEL SCULL

Edie and Andy were at an opening at Lincoln Center with the cameramen as hysterical as if Mrs. Kennedy was making an entrance, lunging at the pair of them. Edie just preened . . . absolutely enjoying every minute of it. So did Andy, who sat humbly with his head down, wearing his leather jacket, and whispering to Edie what to do. Directing her. I could hear him say: “Stand up. Move around. Pose for them.” He knew just the right moment for her to say, “We must go in. We must leave.” Edie loved it. I once asked her, “How does it feel to be a superstar?" and she said, “It’s frightening and glamorous and exciting at the same time. I wouldn’t change it for anything! After the bad and sad times in my life, if s something I want to do.” At intermission that night she stepped out into the aisle of the State Theatre in her black leotards, doing her kind of free-form dancing . . . no music . . . with the whole audience watching.

ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG

I met Edie at an opening. In any situation her physicality was so refreshing that she exposed all the dishonesty in the room. I was always intimidated and self-conscious when I talked to her or was in her presence because she was like art. I mean, she was an object that had been very strongly, effectively created.

SAM GREE’N

Perhaps the greatest triumph of that year for both Edie and Andy was the Warhol Philadelphia exhibition. We stayed at Henry McIlhenny’s house on Rittenhouse Square—Edie and Jane Holzer, Andy, Kenny Lane, Isabel Eberstadt, Taylor Mead, Gerard Malanga. A more bizarre group you couldn’t have found in Philadelphia. On Sunday afternoon we all appeared at his house. We overlapped with the ladies’ tea for the Philadelphia Ballet. We all sat as far away from the other group as we could in a huge sitting room filled with Charles X furniture and great French Impressionist paintings on the walls—both groups just horrified that the other was there.

The butler came over to our group. He was very tall and proper, very stuffy, and about seventy-five years old. He had this great book out. Very grandly he asked what we were going to have for breakfast the next morning. Gerard had never been asked that question before, so he didn’t know what to reply; I wouldn’t have, except I’d stayed there before; Edie knew what was going on, but I don’t think Andy did. Of course, Taylor Mead began rolling his eyes and carrying on. Nobody answered the butler, and he finally had to insist. Staring at Taylor Mead, he said, “Sir, may I have your order for breakfast in the morning?” Taylor looked him up and down—the forty ladies on the other side of the room sitting under Toulouse-Lautrec’s Moulin Rouge painting were all waiting for his reply—and he said, “You.” The butler, without a pause, said, “Yes, sir, and wI’ll there be anything else?” Taylor said, “Well, maybe I’d like some caviar and a quiche Lorraine.” Andy wanted ice cream, and some flowers for his bathwater. Gerard wanted whatever Andy had.

Life

fashion photograph, November, 1965

WALTER HOPPS

That Philadelphia exhibition of Andy’s was one of the most bizarre mob scenes I’ve ever witnessed. In New York, even with the avant-garde, the shows were relatively sedate . . . a kind of inured if not blasé quality about the presentation that kept them from being at all scandalous. But this out-of-town show of Warhol’s 1 Quite astonishing I It was the first survey of all his work—held in the reasonably sedate setting of the little Institute of Contemporary Art there at the University of Pennsylvania. It was crazy. It was the first time I saw a young avant-garde artist have a show mobbed as if it were a movie premiere . . . all kinds of people clamoring to get at Andy as if he were a star. The kind of adulation, curiously, that would be associated with a Salvador Dali daydream. Dali would have loved to have pulled off such a thing and, as far as I know, never quite has.

SAM GREEN

For the preview the press came with their television cameras. It was the biggest thing that happened in Philadelphia

ever

. . . terribly sensational, with lots of cameras and people. The television lights in the crush began to fall into the paintings and tear them; people were crushed up against them.

So I realized that the public opening the next night was going to be even

more

frantic. At the last minute I decided the only thing to do was take down all the pictures so the paintings wouldn’t be ruined. So the grand opening was in fact just people I Andy was mobbed. We were pretty scared because we arrived late from drinks and thousands were jammed into the museum. It was a mob scene and they were all out for blood. Somehow, once inside, we managed to get to an old iron staircase that led up to the ceiling—it hadn’t been used for years and was sealed off at the top by the ceiling itself—and there we were, stuck up above the heads of this unruly crowd pushing and shoving and swarming and carrying on like the mob scene in

The Day of the Locust.

The police were keeping the crowds off the stairs with their sticks. Edie was wearing a Rudi Gernreich dress, a long thing like a T-shirt with sleeves that must have been twenty feet long, rolled up and bunched at the wrist. Then, in this incredible performance, she began baiting the audience: she began to let her sleeves down over the crowd like an elephant’s trunk and then to draw them up again . . . teasing the crowd and working them up. And dancing and talking into the microphone, giving interviews.

Edie meets Mick Jagger at the Scene