Edie (34 page)

Authors: Jean Stein

In one of my sister’s tapes she claimed she’s talking to Henry Kissinger and he was coming on to her, trying to make a date. My sister Polaroided Tiger Morse’s funeral at Frank E. Campbell’s funeral home. I think that’s a bit much.

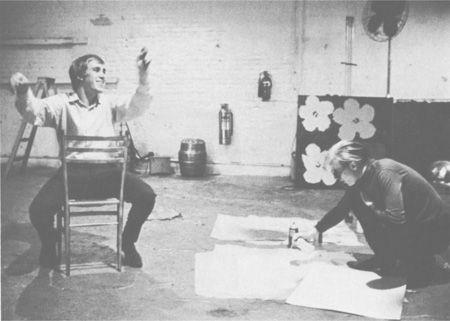

Chuck Wein and Andy

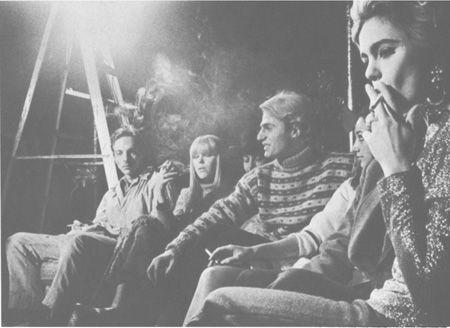

John Palmer, Carol James, Gerard Malanga, Marisa Berenson, and Edie

We never had separate identities, I was always Brigid Polk’s sister. But I gave Brigid her first poke. . . . I have a dog, though.

He

is separate . . . Toto . . . a Yorkshire Terrier who has been with me for eight years and wears eyeglasses. I dress him up. He makes you want to call me Dorothy. He has a tape recorder in his shoe and Mark Cross loafers. He wears coats and hats.

DANNY FIELDS

The Factory mascot was a little boy whose mother was Nico, a singer with the Velvet Underground, and whose father was the French film star Alain Delon. There weren’t many children around. Nico took him everywhere. He was an unhappy Md. Very angry. He was only four or five then; I’m sure he’s changed.

Also in the Velvet Underground was Lou Reed—a little devil, a great talent. Everyone was certainly in love with him—me, Edie, Andy, everyone. He was so sexy. Everyone just had this raging crush . . . he was the sexiest thing going. He was a major sex object of everybody in New York in his years with the Velvet Underground.

NICO

Lou Reed was very soft and lovely. Not aggressive at all. You could just cuddle him like a sweet person when I first met him, and he always stayed that way. I used to make pancakes for him. I had subletted a place on Jane Street when he came to stay with me. That’s when we first did the Electric Circus on St. Mark’s Place; at the time it was called the Balloon Farm.

Lou was absolutely magnificent, but he made me very sad then. . . . He wouldn’t let me sing some of his songs because we’d split. He tried to make it up to me later with that Berlin album . . . I’m from Berlin originally and he wrote me letters saying that Berlin was me.

DANNY FIELDS

After Nico came Viva—very special, very smart, very crazy, and a good mother.

VIVA

Andy was at this party. I screwed up my courage and asked him if I could make a movie. I thought I’d make a few Warhol movies and become a big Hollywood star—starting at the bottom, with Andy my first step toward my ultimate, incredible glory and fame and riches and stardom. Andy said, If you want to take off your blouse, you can make a movie tomorrow. If you don’t want to take it off, you can make another one.”

I was afraid if I didn’t take off my blouse that very next day he would forget me completely. So I put these round Band-Aids on my nipples and took off my blouse. They loved me; they all thought it was an incredible

acting

technique they were seeing.

DANNY FIELDS

Then there was Alan Midgette, the one who impersonated Andy . . . very charming with a movie star’s kind of glamour. He looks part Indian, which accounts for his striking looks. You wouldn’t think he could get away with impersonating Andy on the lecture circuit.

ALAN MIDGETTE

It happened very spontaneously—walking into Max’s Kansas City at about two-thirty in the morning. Paul Morrissey asked me, “Do you want to go to Rochester tomorrow and impersonate Andy at a lecture he’s supposed to give there?”

I said, “No.” I was so used to the idea of not receiving anything for whatever I did at the Factory that the idea of doing a lecture in place of Andy was not interesting at all until Paul said, “You would get six hundred dollars. We’d give you half of the lecture fee. Well go on a tour of colleges.” “Well,” I thought, “six hundred dollars for one day’s work is not bad, and I’m always up for fun like that.”

The next day Paul asked how we could make it work. I said, “Well spray my hair silver and put some talcum powder on top of that. Then well get some Erase, the lightest color they have. I’ll put it all over my face, eyebrows, lips, up my nose, in my ears, and over my hands and arms. Then I’ll put on Andy’s black leather jacket”—he’d handed it to me in Max’s Kansas City the night before—“put the collar up, put on the dark glasses, and that’s it.”

So it worked. Paul sometimes called me Andy by mistake. He couldn’t tell the difference at times. He came along with the film which was the main part of the Warhol presentation. The idea was to show it to students on this tour of colleges and they would ask me questions.

It was easy to impersonate Andy because to the questions I’d always say “Yes” or “No” or “Maybe,” “I don’t know,” “Okay,” “You know, I don’t think about it,” which is the way Andy would have answered the questions anyway.

So I passed. I passed at one o’clock in the afternoon on a clear, sunny day in a gymnasium in Rochester. They had a packed audience.

Paul projected the film. I sat in a corner with my back to the audience. I decided that was the easiest thing to do. I chewed gum a lot, because Andy did. It gets your face moving quite a bit, so the audience couldn’t tell very much about it when I had to turn around to answer questions after the film was over. The first one was: “Why do you wear so much make-up?” I said, “You know, I don’t think about it.” They let it go.

I think perhaps the thing began to blow up in Salt Lake City when “Andy” was supposed to talk to three thousand students. As we landed, we heard over the loudspeaker, “Please be careful getting off the plane. Watch out for your hats because it’s really windy today.”

Sure enough, when I got off the plane, the wind blew off all the talcum powder I’d put in my hair, just blew it right out like a puff of smoke. All these people were standing there waiting for us. I got into a car and this guy started taping me. He was very shy. Finally he said, “What is that stuff on your face?”

I said, “I have a skin condition.”

He got very embarrassed, and said, “Oh, I’m sorry.”

At one of the universities the students wanted to do an interview with Andy for their television studio. I was trying to get my face in a position where the viewer really couldn’t see the form of it. As I stared at the monitor, I suddenly realized I looked exactly like Mar-cello Mastroianni.

The thing finally broke when I was in Mexico. The next thing I knew, the story was in

Time

and

Newsweek.

It was all over the place. I haven’t seen much of Andy since then. it’s not the kind of thing we ever sat around and laughed about.

ONDINE

Andy loved this guy called Rod La Rod. Isn’t that perfect? Every time Andy appeared with his camera, Rod La Rod would throw it down and beat up Andy, and they’d have this fistfight right on the set. They’d smash each other to ribbons. Then they’d make up. It was just wonderful. They’d found each other. They were divine. We kept telling Andy: “Oh, God, he’s awful for you.”

Andy’d say, “I know. I know.” It was so amusing.

Do you remember when Lester Persky gave a party in the Factory for the fifty most beautiful people? People came like Montgomery Clift . . . just thousands of people there . . . the really great stars. I’ll never forget the door of the freight elevator opening up with Lester Persky and Tennessee Williams standing there with their arms interlocked

carrying Judy Garland. Everybody refused to recognize her. Simply refused. The only people that were paid any attention to were Edie, myself . . . people in the Warhol contingent. Nureyev, at one point, asked Judy Garland to twist. They got up. Everybody turned away. Just totally. The whole party was involved with drugs and the new kind of celebrity. Even Nureyev was considered very old hat.

Edie’s three-minute screen test at the Factory, March, 1965

DANNY FIELDS

When Edie entered the Factory scene, I thought it was nice that the Cambridge boys had imported their own private princess. It seemed a nice transfer of domain because, before that, she’d just been a Cambridge legend. She was rich, glamorous, beautiful, and she was instantly adored.

Edie was the First Lady and Andy’s prime companion, so there was an on-going struggle for her favor and attention . . . a rivalry for her affection. She was the greatest of the superstars.

RENÉ RICARD

The term “superstar” was coined and invented by Chuck Wein. The big words then were “super” and “fantastic.” Jane Holzer may have started “super.” Certainly that was her big word. It was the first time the words “super” and “star” were coupled together. I’ve found it only once before—in an obscure fan magazine from the Thirties.

DANNY FIELDS

The superstar was a kind of early form of women’s liberation. They were so smart, beautiful, aristocratic, and independent. Edie, Nico, Viva, and the others. They were like Garbo and Bette Davis in that system of the Thirties. They were indulged by everybody. They were as smart as any of the men around. Everybody, from little boys to old faggots, fell in love with them . . . just as those

stars of the Thirties inspired their leading men, the directors, the producers to fall in love. They were definitely superior beings and very involved. They’re the women we all want to worship. I mean, Virgin Marys. At the same time they were very destructive people—self-destructive and other-people-destructive. They were riding the whirlwind.

VIVA

None of the superstars really had a role in the Factory. Edie, I figured out, who was non-Catholic, was never actually a part of the

true

family. And, being a woman, she played an inferior role. In the Catholic Church women are supposed to play a big role—I mean, we have the whole nunnery and so on—but women have

no

voice in the running of the Church. They can never be priests. Their dirty menstrual bodies cannot possibly touch the sacred host.

The popular view of Andy is as a Father Confessor, but I don’t go along with that. He was more like an attention-giver. If you had a father who read the paper at the dinner table and you had to go up and turn his chin to even get him to look at you, then you had Andy, who would press the “on” button of the Sony the minute you opened your mouth. And we were encouraged to perform. The Factory was a way for a group of Catholics to purge themselves of Catholic repression . . . and Catholic repression in the Fifties was so extreme that the only way to liberate oneself from it was to react in the completely opposite direction, and then hopefully level off after that.

Andy Warhol would try to pick out men for me. He’d say, “Now go with this one, go with that one.” All these men in whom I had no interest whatsoever. He was always coming up with these guys I think he was interested in. He would try to get

me

to go off with them. He’d say, “Big cock, big dick. He’s got a big cock, go with him.” And yet if you so much as tried to touch Andy, he would actually shrink away. Shrink. I mean shrink backwards and whine. Many times I used to make a grab at Andy, kiddingly, or touch him, and he would cringe. Whine, “Aw, Viva, awww.” We were all always touching Andy just to watch him turn red and shrink. like the proverbial shrinking violet.