Eight Little Piggies (19 page)

Read Eight Little Piggies Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

Halley begins the last paragraph by admitting a bias that he cannot correct:

If it be objected that the water of the ocean, and perhaps some of these lakes, might at the first beginning of things, in some measure contain salt, so as to disturb the proportionality of the encrease [

sic

] of saltness in them, I will not dispute it…

How lovely, I said to myself. He is about to state the principle that bias must lie against a favored outcome. I must note this and point it out to students. I read on and was not disappointed. Halley makes the argument with fine precision (continuing from the quotation above):

…but shall observe that such a supposition would by so much contract the age of the world within the date to be derived from the foregoing argument….

I smiled benignly, began to read on, and then experienced the moment of truth so like that classic scene of cartoon or comedy when the policeman sees a flying mouse or a walking snowman, smiles happily with a “how-nice, a-flying-mouse” look, then does a double take, drops whistle from mouth in astonishment, and says, “A flying mouse!” Wait a minute! Halley is supposed to be arguing for an age

longer

than tradition, an expansion of biblical limitations. But he actually says that a bias he can’t remove will make the earth seem

older

than it really is, the very kind of bias—one favoring your hypothesis—that

must

be avoided. (If a bag contains one hundred beans and you observe that one new bean is added each day, you will assume, by analogy with Halley’s argument about originally saltless oceans, that beans have been added for one hundred days. But if the bag started with twenty-five beans, the process will only be seventy-five days old, not one hundred as you estimated. In the same manner, if the oceans started with some salt, but you assume they began saltless, your age by Halley’s method will be greater than the true age.)

I then became seriously puzzled. Does Halley have his methodology backward? What is going on? How can he be trying to expand the earth’s age and then admit a bias that will make it appear older? Either Halley was a methodological dunce or something must be desperately wrong with the traditional view that he was trying to set a minimal age for the earth. In fact, Halley is telling us that he has set a

maximal

age, and he is clearly damned pleased with himself. I read further (again continuing the last quotation):

…the foregoing argument, which is chiefly presented to refute the ancient notion, some have of late entertained, of the eternity of all things.

So Halley thought he was doing the exact opposite of what all posterity has attributed to him. He contends that he was establishing a maximal age to refute a notion of eternity. We say that he was seeking a minimal age to expand the literal biblical chronology. Why—given the admirable clarity of Halley’s words—have we so grievously misstated his intent?

Eternity is no longer an issue for us (in discussing the earth’s duration). We all assume that our planet had a determinable beginning. Since we have not entertained this alternative for several centuries, we lack a context for grasping Halley’s last paragraph. We read right through his words because they make no sense to us. We, as veterans of several creationist waves from Scopes to Arkansas, fully understand the threat to science of biblical literalism. We are therefore led to read Halley falsely in our light and see him as a fighter for expanded time rather than, as he insists, a measurer who would fix an actual date in order to eliminate the possibility of infinite existence.

Fortunately, I chose to dust off Halley’s article while I was busy reading the protogeologies of late seventeenth-century British savants (primarily Thomas Burnet’s

Sacred Theory of the Earth

) for another project (see my book

Time’s Arrow, Time’s Cycle

). I was therefore predisposed to read Halley as he intended.

We can grasp why eternity seemed an even greater danger than biblical literalism only when we understand Halley and his generation as struggling to find the basis for a science of historical events (both Burnet and Halley were friends of Newton and members of a scientific generation with common goals). Burnet, for example, rails on and on through 400 pages against the idea of eternity, and he fights this great battle, or so he says, because eternity precludes the possibility of meaningful history defined as a sequence of distinct and recognizable events linked by ordinary ties of cause and effect. Burnet identifies, as his main enemy:

…this Aristotelian doctrine, that makes the present form of the earth to have been from eternity, for the truth is, this whole book is one continued argument against that opinion.

If the earth is eternal, then no event can be distinctive. All must occur again and again, and we fall into incomprehension, for our struggles and dreams lose any meaning as unique events in finite time. Eternity destroys history; it “takes away the subject of our discourse,” as Burnet writes.

Jorge Luis Borges, in his uniquely exquisite way, expressed the incomprehensibility of infinity in

The Book of Sand

. In this story, Borges procures an infinite book. He cannot find its end, for no matter how furiously he turns the pages, as many remain between him and the back cover. The book contains small illustrations, spaced 2,000 pages apart. None is ever repeated, and Borges fills a notebook with their sequence, never coming any closer to a termination. Finally, he understands that this precious book is actually monstrous and obscene, and he loses it permanently on a shelf deep in the stacks of the Argentine National Library. He has understood the dilemma of eternity: “If space is infinite, we may be at any point in space. If time is infinite, we may be at any point in time.”

Halley sought to disprove this most unthinkable of systems by resolving Borges’s dilemma and setting a definite point—an actual age in years—for the earth’s beginning. Halley, in short, was fighting for history. If we view him as a great historical scientist who advanced his proposal for dating the earth as a blow for rationality itself, then we can understand the last paragraph and its message for us.

Halley fights for history from both sides; his short article is both a specific proposal for measuring the earth’s age and a beautifully crafted defense of historical science in general. He does argue against biblical literalism—to gain enough time so that ordinary causes may shape geological history. Without time in abundance, we will need miracles to cram such richness into just a few thousand years. The traditional reading of Halley stops here.

But Halley insists that his struggle for a comprehensible history proceeds primarily from the other end, by stealing time from eternity—for the bias of his method can only justify its employment against a claim for

greater

ages than he might measure. I think that we must take Halley at his word, for he was too astute a methodologist to misuse the primary criterion of bias. Halley believed that he had set a maximal age for our planet. Surely, the earth could not be eternal, for biases in Halley’s method could only make it younger than his own measured maximum.

When we understand what Halley really sought, we can also grasp the reason for his failure. He was trying to establish a rational science of history. To do this, he needed a criterion that would change constantly in a recognizable way through time—so that each moment would be distinctly different from every other, thus avoiding Borges’s dilemma. He thought that the accumulation of salt in oceans and lakes, linearly increasing through time, would provide such a criterion. The primary struggle of historical science ever since Halley has centered upon the search for phenomena that change constantly and therefore mark the passage of time. Halley knew exactly what history needed, but he chose the wrong criterion for interesting reasons.

Halley may have burst the bonds of biblical literalism, but he had no inkling whatever of time’s true immensity. (The 100-million-year age so often attributed to him is Joly’s nineteenth-century date using Halley’s method. Halley himself never dared to think in more than thousands.) The clearest evidence for Halley’s limited perspective, a notion shared by all contemporaries who tried to date the earth (see next essay), lies within his argument about salt, when he laments that ancient Romans and Greeks did not measure the salinity of oceans:

It were to be wished that the ancient Greek and Latin authors had delivered down to us the degree of the saltness of the sea, as it was about 2,000 years ago; for then it cannot be doubted but that the difference between what is now found and what then was, would become very sensible.

If Halley had recognized how infinitesimally tiny a fraction of earth history these 2,000 years actually represented, he would not have been so confident that the increment between then and now could set a metric for determining the beginning itself. Two thousand years was an appreciable part of the tens of thousands that his wildest fancies could conceive.

An earth as young as Halley imagined might have provided criteria for history in such simple physical processes as the influx of salt from rivers. But, as I argued above, simple systems generally equilibrate or reach some completed state over truly great durations. Components of atmospheres and oceans reach equilibrium; they do not change steadily over billions of years. Unless we can find something truly big (fuel of a star) or numerous (number of atoms subject to radioactive decay) relative to time available, physical objects make poor criteria of history.

The best signs of history are objects so complex and so bound in webs of unpredictable contingency that no state, once lost, can ever arise again in precisely the same way. Life, through evolution, possesses this unrepeatable complexity more decisively than any other phenomenon on our planet. Scientists did not develop a geological time scale—the measuring rod of history—until they realized that fossils provided such a sequence of uniquely nonrepeating events.

When I began these essays in 1974, I chose for my general title a phrase from the last paragraph of Darwin’s

Origin of Species

—“this view of life.” I selected this passage because I love the science of history. Darwin used this phrase to contrast the richness of life’s history with the timeless cycling of simpler physical systems, in particular planets in their orbits. Halley knew what a science of history required, but he could not grasp why simple systems did not provide good criteria because he dared not even imagine how old the earth might really be. Darwin sensed the scope of time and knew that only life’s complexity could map its richness:

There is grandeur in this view of life…. Whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

Postscript

Although this is one of the few articles on Halley written during the season of his celebrated eponymous object, but not treating the subject of comets at all, I must nonetheless report briefly on my viewing experience, because I saw something so touching and learned something important thereby.

I had been waiting all my conscious life, and I wasn’t going to miss it. Views from Boston were especially lousy (low on the horizon and therefore invisible from just about everywhere), and the comet was putting on a crummy show anyway (and anywhere). Further south meant higher in the sky and a better shot at seeing something. I had to visit the Smithsonian Tropical Research Station in Panama anyway, so I timed my trip for an optimal view. A staff scientist at the Institute picked me up at 3:00

A.M.

, as the best time for sighting came just before dawn. We drove far way from the city of Panama and set up a telescope in a dark field.

That night and morning provided two special pleasures. First, Halley’s comet made quite a surprising impression on me. I had been told many times to expect nothing interesting or exciting, so I came prepared for disappointment (and only because a lifetime’s promise to oneself cannot be easily canceled in the mind). I hoped for little, but saw quite a bit. The comet looked so different from everything else up there—from all the pinpoints of light that I know so well as a lifelong stargazer. The comet was faint, but fuzzy rather than concentrated. Everything else, however bright, was a point; Halley’s comet formed a broad line subtending nearly ten degrees of celestial arc. If you know the night sky as a friend, something so different amidst all your buddies can be awesome, if smallish.

Second, I was moved far more by a human scene. As we drove back to the city of Panama along the causeway by the sea just as the sun began to rise, I noticed crowds of Panamanian people, ever denser the closer we got to town (for the majority had to walk, even though viewing improved with distance). Most were family groups. Fathers and mothers pointed to the sky, showing the comet to their young children telling them perhaps that they might live to see it again. As the dawn broke, these people appeared as silhouettes against the brightening sky—parents pointing upward towards their once-in-a-lifetime view. Hundreds of poor and carless citizens had bustled their children out long before dawn and walked away from the city lights to line the causeway with human curiosity. Who will dare to say that people do not have a sense of wonder, or do not care about science and nature, if a little fuzzy line, properly publicized, can make us all citizens of the universe, at least for a short morning?

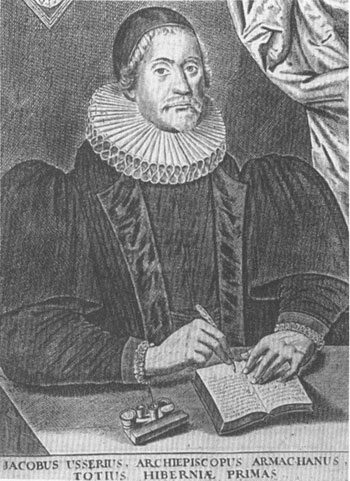

I AM UNCOMFORTABLE ENOUGH

in a standard four-in-hand tie; pity the poor seventeenth-century businessmen and divines, so often depicted in their constraining neck ruffs. The formidable gentleman in the accompanying engraving commands the Latin title

Jacobus Usserius, Archiepiscopus Armachanus, Totius Hiberniae Primas

, or James Ussher, Archbishop of Armagh, and Primate of All Ireland. He is known to us today almost entirely in ridicule—as the man who fixed the time of creation at 4004

B.C.

, and even had the audacity to name the date and hour: October 23 at midday.

Let me begin with a personal gloss on the caption to this engraving, for my misreading embodies, in microcosm, the entire theme of this essay. I confess that I have always been greatly amused by the term

primate

, used in its ecclesiastical sense as “an archbishop…holding the first place among the bishops of a province.” My merriment must be shared by all zoologists, for primates, to us, are monkeys and apes—members of the order Primates. Thus, when I see a man described as a “primate,” I can’t help thinking of a big gorilla. (Humans, of course, are also members of the order Primates, but zoologists, in using the term, almost always refer to nearly 200 other species of the group—that is, to lemurs, monkeys, and apes.)

But my amusement must be labeled as silly, parochial, and misguided. The title comes from the Latin

primas

, meaning “chief” or “first.” In the mid-eighteenth century, Linnaeus introduced the word to zoology as a designation for the “highest” order of mammals—the group including humans. But the ecclesiastical usage has an equally obvious claim to proper etymology and substantial precedence in usage (the

Oxford English Dictionary

traces this meaning to 1205). Thus, we zoologists are the usurpers, not the guardians of a standard. (I wonder if preachers laugh when they see the term in a zoological book and think of a baboon running about in a neck ruff.) In any case, the archbishop of Armagh is titular head, hence primate, of the Anglo-Irish church, just as the archbishop of Canterbury is primate of all England.

This little tale mimics the forthcoming essay in miniature for two reasons:

1. I shall be defending Ussher’s chronology as an honorable effort for its time and arguing that our usual ridicule only records a lamentable small-mindedness based on mistaken use of present criteria to judge a distant and different past—just as our current amusement in picturing a primate of the church as a garbed ape inverts the history of usage, for the zoological definition is derivative and the ecclesiastical primary.

2. The mental picture of a prelate as a garbed ape reinforces the worst parochialism that scientists often invoke in interpreting their history—the notion that progress in knowledge arises from victory in battle between science and religion, with religion defined as unthinking allegiance to dogma and obedience to authority, and science as objective searching for truth.

James Ussher (1581–1656) lived through the most turbulent of English centuries. He was born in the midst of Elizabeth’s reign and died under Cromwell (who gave him a state funeral in Westminster Abbey, despite Ussher’s royalist sentiments and his previous support for the executed Charles I). As a precocious scholar with a special aptitude for languages, Ussher entered Trinity College, Dublin, at its founding in 1594, when he was only thirteen years old. He was ordained a priest in 1601 and became a professor at Trinity (1607) and then vice chancellor on two occasions in 1614 and 1617. With his appointment as Archbishop of Armagh in 1625, he became head (or primate) of the Anglo-Irish church—a tough row to hoe in this preeminently Catholic land (“Romish” or “papist” as Ussher always said in the standard deprecations of his day). Ussher was vehement and unrelenting in his verbal assaults on Roman Catholicism (he wasn’t too keen on Jews and other “infidels” either, but the issue rarely came up). His 1626 “Judgement of the Arch-Bishops and Bishops of Ireland” begins, for example:

The religion of the papists is superstitious and idolatrous; their faith and doctrine erroneous and heretical; their church…apostatical; to give them therefore a toleration, or to consent that they may freely exercise their religion…is a grievous sin.

One may cringe at the words (and no one can take Ussher as a model of toleration), but he was, in fact, regarded as a force for moderation and compromise at a time of fierce invective (read Milton’s anti-Catholic pamphlets sometime if you want to get a feel for the rhetoric of those troubled years). Despite his opinions, Ussher continued to espouse debate, discussion, and negotiation. He preached to Catholics and delighted in meeting their champions in formal disputations. His own words were harsh, but he believed in triumph by force of argument, not by banishment, fines, imprisonment, and executions. In fact, even the hagiographical biographies, written soon after Ussher’s death, criticize him for lack of enthusiasm in the daily politics of ecclesiastical affairs and for general unwillingness to carry out policies of intolerance. He was a scholar by temperament and, at best, a desultory administrator. He was in England at the outbreak of the civil war in 1642 and never returned again to Ireland. He spent most of his last decade engaged in study and publication—including, in 1650, the source of his current infamy:

Annales veteris testamenti, a prima mundi origine deducti

, “Annals of the Old Testament, deduced from the first origin of the world.”

Ussher became the symbol of ancient and benighted authoritarianism for a reason quite beyond his own intention. Starting about fifty years after his death, most editions of the “authorized,” or King James, translation of the Bible began to carry his chronology in the thin column of annotations and cross-references usually placed between the two columns of text on each page. (The Gideon Society persisted in placing this edition in nearly every hotel room in America until about fifteen years ago; they now use a more modern translation and have omitted the column of annotations, including the chronology.) There, emblazoned on the first page of Genesis, stands the telltale date: 4004

B.C.

Ussher’s chronology therefore acquired an almost canonical status in English Bibles—hence his current infamy as a symbol of fundamentalism.

To this day, one can scarcely find a textbook in introductory geology that does not take a swipe at Ussher’s date as the opening comment in an obligatory page or two on older concepts of the earth’s age (before radioactive dating allowed us to get it right). Other worthies are praised for good tries in a scientific spirit (even if their ages are way off—see previous essay on Halley), but Ussher is excoriated for biblical idolatry and just plain foolishness. How could anyone look at a hill, a lake, or a rock pile and not know that the earth must be ancient?

One text discusses Ussher under the heading “Rule of Authority” and later proposals under “Advent of the Scientific Method.” We learn—although the statement is absolute nonsense—that Ussher’s “date of 4004

B.C.

came to be venerated as much as the sacred text itself.” Another text places Ussher under “Early Speculation” and later writes under “Scientific Approach.” These authors tell us that Ussher’s date of 4004

B.C.

“thus was incorporated into the dogma of the Christian Church” (an odd comment, given the tradition of Catholics, and of many Protestants as well, for allegorical interpretation of the “days” of Genesis). They continue: “For more than a century thereafter it was considered heretical to assume more than 6,000 years for the formation of the earth.”

Even the verbs used to describe Ussher’s efforts reek with disdain. In one text, Ussher “pronounced” his date; in a second, he “decreed” it; in a third, he “announced with great certainty that…the world had been created in the year 4004

B.C.

on the 26th of October at nine o’clock in the morning!” (Ussher actually said October 23 at noon—but I found three texts with the same error of October 26 at nine, so they must be copying from each other.) This third text then continues: “Ussher’s judgment of the age of the earth was gospel for fully 200 years.”

Many statements drip with satire. Yet another textbook—and this makes six, so I am not merely taking potshots at rare silliness—regards Ussher’s work as a direct “reaction against the scientific explorations of the Renaissance.” We then hear about “the pronouncement by Archbishop Ussher of Ireland in 1664 that the Earth was created at 9:00

A.M.

, October 26, 4004

B.C.

(presumably Greenwich mean time!)” Well, Ussher was then eight years dead, and his date for the earth’s origin is again misreported. (I’ll pass on the feeble joke about Greenwich time, except to note that such issues hardly arose in an age before rapid travel made the times of different places a matter of importance.)

Needless to say, in combating the illiberality of this textbook tradition, I will not defend the substance of Ussher’s conclusion—for one claim of the standard critique is undeniably justified: A 6,000-year-old earth did make a scientific geology impossible because any attempt to cram the empirical record of miles of strata and life’s elaborate fossil history into such a moment requires a belief in miracles as causal agents.

Fair enough, but what sense can be made of blaming one age for impeding a much later system that worked by entirely different principles? To accuse Ussher of delaying the establishment of an empirical geology is much like blaming dinosaurs for holding back the later success of mammals. The proper criterion must be worthiness by honorable standards of one’s own time. By this correct judgment, Ussher wins our respect just as dinosaurs now seem admirable and interesting in their own right (and not as imperfect harbingers of superior mammals in the inexorable progress of life). Models of inevitable progress, whether for the panorama of life or the history of ideas, are the enemy of sympathetic understanding, for they excoriate the past merely for being old (and therefore both primitive and benighted).

Of course Ussher could hardly have been more wrong about 4004

B.C.

, but his work was both honorable and interesting—therefore instructive for us today—for at least four reasons.

1. The excoriating textbook tradition depicts Ussher as a single misguided dose of darkness and dogma thrown into an otherwise more enlightened pot of knowledge—as if he alone, representing the church in an explicit rearguard action against science and scholarship, raised the issue of the earth’s age to recapture lost ground. No idea about the state of chronological thinking in the seventeenth century could be more false.

Ussher represented a major style of scholarship in his time (see previous essay on Halley for discussion of another contemporary style—one more congenial to our current views, but no more popular than Ussher’s mode in a seventeenth-century context). Ussher worked within a substantial tradition of research, a large community of intellectuals striving toward a common goal under an accepted methodology—Ussher’s shared “house” if you will pardon my irresistible title pun. Today we rightly reject a cardinal premise of that methodology—belief in biblical inerrancy—and we recognize that this false assumption allowed such a great error in estimating the age of the earth. But what intellectual phenomenon can be older, or more oft repeated, than the story of a large research program that impaled itself upon a false central assumption accepted by all practitioners? Do we regard all people who worked within such traditions as dishonorable fools? What of the scientists who assumed that continents were stable, that the hereditary material was protein, or that all other galaxies lay within the Milky Way? These false and abandoned efforts were pursued with passion by brilliant and honorable scientists. How many current efforts, now commanding millions of research dollars and the full attention of many of our best scientists, will later be exposed as full failures based on false premises?

The textbook writers do not know that attempts to establish a full chronology for all human history (not only to date the creation as a starting point) represented a major effort in seventeenth-century thought. These studies did not slavishly use the Bible, but tried to coordinate the records of all peoples. Moreover, the assumption of biblical inerrancy doesn’t provide an immediate and dogmatic answer—for many alternative readings and texts of the Bible exist, and scholars must struggle to a basis for choice among them. As a primary example, different datings for key events are given in the Septuagint (or Greek Bible, first translated by the Jewish community of Egypt in the third to second centuries

B.C.

and still used by the Eastern churches) and in the standard Hebrew Bible favored by the Western churches.

Moreover, within shared assumptions of the methodology, this research tradition had considerable success. Even the extreme values were not very discordant—ranging from a minimum, for the creation of the earth, of 3761

B.C.

in the Jewish calendar (still in use) to a maximum of just over 5500

B.C.

for the Septuagint. Most calculators had reached a figure very close to Ussher’s 4004. The Venerable Bede had estimated 3952

B.C.

several centuries before, while J. J. Scaliger, the greatest scholar of the generation just before Ussher, had placed creation at 3950

B.C.

Thus, Ussher’s 4004 was neither idiosyncratic nor at all unusual; it was, in fact, a fairly conventional estimate developed within a large and active community of scholars. The textbook tradition of Ussher’s unique benightedness arises from ignorance of this world, for only Ussher’s name survived in the marginal annotations of modern Bibles.