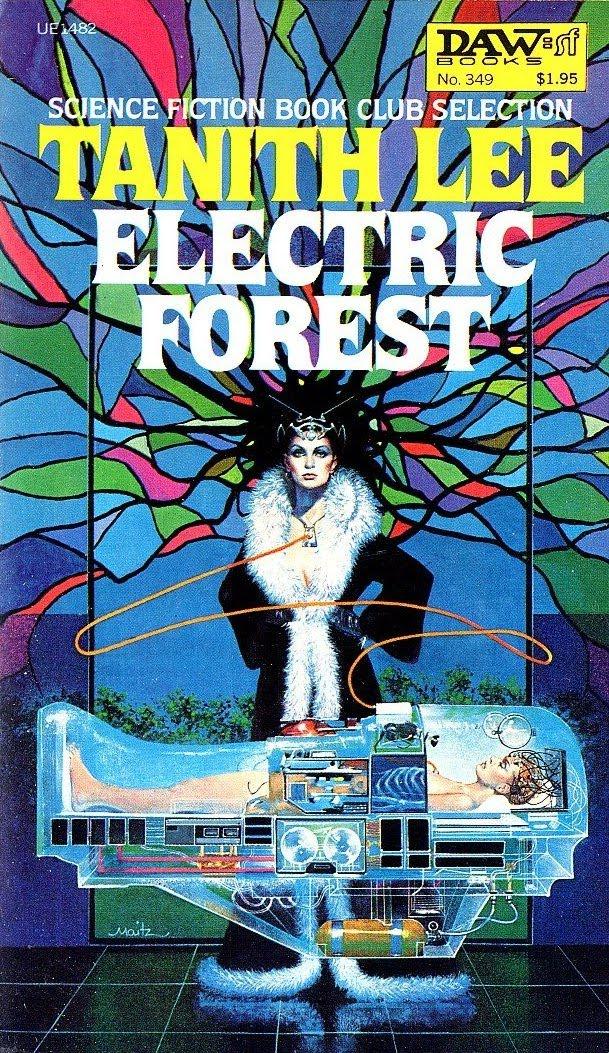

Electric Forest

Authors: Tanith Lee

Electric Forest

by TANITH LEE

Nelson Doubleday, Inc. Garden City, New York

Copyright © 1979 by Tanith Lee All rights reserved

Published by arrangement with

DAW Books, Inc. 1301 Avenue of the Americas New York, New York 10019

Printed in the United States of America

to

Don and Elsie Wollheim

with affection and thanks

Contents

Pre-Screening: Christophine del Jan

1

1.

Quarry and Hunter 3

2. Venus Rising 25

3.

The Proving-Ground 45

4. Crossing the Line 73

5. Secundo

93

6. In the Forests of the Night

113

Post-Screening Sonogram

141

Pre-Screening: Christophine del Jan (This Presentation is Classified)

The following document has been compiled from the data tapes, and prepared in narrative-descriptive form, in order to throw an ultimate light upon what took place between 10-4-1 and 9-1-2 of the Third Quarter,

Blue and early Fall, Indigo.

Required reading can be, at this stage, irksome. I would ask, however, that you follow the manuscript on your screen in strict sequence, resisting the impulse to anticipate. After all, the motivation of the subject is

the key element here, emotion and psychology providing clues to that motivation.

Nothing can be learned without some measure of risk, and, more vital still, of patience.

Additional material is naturally available via optocon and audio. But this, too, I would ask you to delay using until the manuscript itself has been absorbed.

The screen is now at your disposal.

C.d.J.

1. Quarry and Hunter

i

Ugly stood alone before the processing machine.

The machine made certain types of cottene clothing, but Ugly never saw the syntho-cotton fed in at one tube above, nor the crisp white garments snowing out from the other below. Neither did she witness the actual metamorphosis that went on inside the machine in front of her. In the restricted space, three meters

by two, Ugly stood alone with the processing machine and ran her stubby hands, clumsily but effectively,

over the bank of green and red keys. It was simple to keep the machine functioning. The task should have

left her mind free to think of other things.

Unfortunately, Ugly had very little to think about.

Ugly's shift comprised three hours on alternate days five days a Dek; that was each oneday, threeday,

fiveday, seven-day and nineday. Every fifth Dek was free. For this program of work, Ugly received two

hundred astrads each calendar month (four Deks), of which about one hundred and fifty went on

accommodation, food and essentials. Fifty astrads were nearly always left over to be spent on relaxation

and

4

pleasure. Unfortunately, again, Ugly was not in an ideal position to spend them.

Ugly's name, of course, was not actually "Ugly." That Was merely what most people children,

workmates called her. It was not even a particularly cruel name any more, simply blisteringly accurate.

No longer spoken in malice, it had lost some of its intrinsic offense and gained some. Ugly herself had

never commented on the matter, either way, nor on her real and registered name, Magdala Cled.

On any planet of the Earth Conclave, fetal conception was the controlled result of selective, artificial

impregnation. This ensured that all children born were healthy. Occasionally, however, mistakes occurred in

the area of contraception, and a fetus was conceived biologically. Sometimes, such children were less than perfect. It had happened that Magdala Cled was one of these.

Her mother was a licensed prostitute; no one had bothered to identify her father. Intent on trade, the

woman had forgone abortion until too late. She had subsequently dispelled her baby and dumped it, with the required five hundred astrads, on the State. Magdala had grown up in a state childrens home.

A potential intelligence and interest had quickly submerged beneath regulation mechanical schooling that

gave no outlet for speculation or the asking of even the most basic questions. It submerged, too, beneath the primitive malignancy of her fellow inmates, who (in their defense) were half-afraid of Magdala. For it was a society of regular features and well-formed physiognomy, and monsters were rare.

"Ugly!" the children screamed, as they tore Magdala's hair out, tripped her, stuck into her small sharp

objects, pinched and kicked her. Almost as if, by constant assault, they could change her into something less

dreadful.

But Magdala Cled, re-named Ugly, only grew uglier.

Just under one and a half meters in adult height, a great engine seemed to have descended upon her,

squashing her

5

downwards and sideways, and twisting her for good measure. Squat, square and irreparably leaning,

Magdala walked with a sort of part-lagging, part-hopping step. From her skew shoulders, arms hung like

afterthoughts, with spatulate afterthoughts of hands on them. And from her head, an afterthought of thin

murky hair, chopped off at the neck. The modeling of the skull itself did show some mocking promise.

Under other circumstances, it could have been the skull of an aware and creative woman. The face might have been poignant, though never pretty. But even that had not been possible for it. The flattened nose, the

left eyelid which lay permanently almost closed on the gray-white cheek, had seen to that. Only the mouth was well-formed, though the teeth had broken long ago and been replaced by haphazard dental implants, shabby as the fate which had necessitated them.

Certainly, Magdala, in the most absolute sense, merited her second name. It suited her; she would have been the last to deny that.

Only inside her, never let out, the bewildered anger hid, the pain and fury. She hid them also from herself,

when she could, did ugly Magdala.

On Earth Conclave planet Indigo, cosmetic surgery cost more astrads than a processory operative could

save in seven years. Even the un-spendthrift Magdala. For there was not much call for such surgery, and the fee compensated. Besides, Magdala had only to glimpse herself in a reflective surface to know she

would need more work upon herself than any physical human body could stand.

She was a hopeless case.

And if she thought about anything, as her stunted efficient fingers scrambled over the keys of her machine, ugly Magdala thought of that. A formless and useless sort of thinking, more like an ache in her brain than a thought. While sometimes superimposed upon the basic hopelessness, was a list of that day's familiar

miseries the looks of

6

strangers: pity and revulsion, the disgusted and desensitized looks of acquaintances (there were no friends).

And under it all, checked yet eternal, blazing anguish, howling.

At thirteen hours, Indigo noon, Magdala's shift finished. However, Magdala's relief was late, as her reliefs

always were. Magdala, unprotesting, stayed at her post, until another girl slipped into the three-by-two cell.

'Thanks, Ugly," said the girl, and it was obvious she used the epithet now only as identification, no hurt

consciously intended. "I guess I'm late again. Had to fix myself up." The girl was attractive, even in her

cottene overall. She edged past Magdala and pressed at the key bank with an inch of raspberry nail. Her

hair was the induced color of eighteen-carat gold, and she shook it contemptuously at the machine. "Three hours of this. Jesus. Still, I may be on the display benches next Dek."

Magdala stood in the cell doorway, watching the girl. Magdala's smeared plasticine face was quite illegible. The display benches had two-hour shifts only, and earned an extra fifty astrads per month, but, open to

inspection, they were manned solely by the most good looking men and women.

The golden girl yawned into a trap of raspberry nails.

"Go on, Ugly. Beat it. I'm expecting a bench supervisor by in a minute, and it's private/'

Ugly left the machine cell, and made her stumbling exit along the corridor. Other machine cells opened off in the right-hand wall. On the left the lower extensions of solar generators thrummed. At the check point, Magdala shed her overall into a disposal chute. Clad in her own shapeless utility garment, she sank in the elevator and emerged presently in the ozonized city air.

It was Blue, the season that on Indigo preceded Fall. On the shaved sloping lawns of the city the amber summer grass was turning the shade of wood-smoke; on the um-

7

brella-formed trees along the sidewalks, the leaves hung like lapis lazuli. Above, the tall slender

blocks of steel and glazium rose into a sky which was also intensely blue, and warm with the zenith

sun of thirteen o'clock. A steady concerted vibration came from the city; the hum of solar

generators at work on the high roofs and sky-links overhead, the purr of unseen vehicular traffic

passing on the underground roadways. There was, too, the murmur of countless small

devices-automatic sprinklers and fans, vendors, clocks, the gem-bright advertisements on the

walls of occasional buildings, the faint regular throbbing of the live pavement at the sidewalk's

center, and of a thousand elevators, moving stairs, reversible windows, sliding doors.

There were not many people abroad here in the commercial area of the city, for the thirteen-hour

shift had checked out almost an hour before.

In the isolation, a handsome young man, passing on the slow outer section of the live pavement,

glided by Magdala. His hair was pale and silken, and he was listening to music through the small

silver discs resting lightly in his ears, but his eyes, wandering, alighted on the woman, and at once

f l

inched frantically into reaction. Once or twice Magdala had caught a comment from those who

were shocked by her appearance. "It's horrible. If I looked like her, I'd ask for work in one of the

out-city plants." And another:

If

I looked like that, I'd take enough analgens to see I didn't wake

up." Magdala was accustomed to it all, the looks, the words. She seemed not to register them.

Seemed not to.

Carried a short distance away, the pale-haired young man risked turning his head. Glazed in his web of externally noiseless music, he stared at Magdala, disbelieving.

Magdala did not use the live pavement. Even getting onto the slow outer strip proved difficult

because of her awkwardness. And people did not like to travel with her, would

wait till meters of the strip had gone by before they would step on in her wake. For this same reason

she avoided the sub-transport, the sensit theaters, and most public haunts.

8

She walked a great deal, on lonely thoroughfares, in her agonized, lurching fashion.

Six blocks from the clothing processory, the sidewalks opened into arcades and apartment-stores.

These could be the most unnerving moments of Magdala's journey, as, head bowed, gaze carefully blind,

she fumbled through the periphery of the crowds. Sometimes people supposed her shortness to be that of a

child, stopped to guide her, and recoiled in alarm. But today the arcades were not crowded and there were

no incidents.

On the far side of the arcades lay an azure park where tame white or black doves fluttered about. Beyond

the park towered seven Accomat blocks, in the fifth of which Magdala lived.

The Accomat was one of the cheapest ways to exist. Each apartment had a single main area three by four

meters, with a bathroom cubicle half that size, and the normal accessories of food-dial, pay-dial and Tri-V screen, and limited furniture which unfolded from the wall. The perimeter variety also had windows. The inner did not, and here washed-air came through vents and second-hand daylight through refractors and shafts. Magdala's Accomat did not have a window.

The door shot wide in response to the pressure of her thumb in the print-lock. Magdala moved into the

windowless, dim-lit, washed-air cell, just fractionally larger than the cell in which she worked. There was

small evidence of her personality in this chamber, and what evidence there was had been cunningly

concealed.

Now she did not hesitate, except for the constant physiological hesitation of her walk. She crossed to her

pay-dial.