Embers of War (59 page)

Authors: Fredrik Logevall

Tags: #History, #Military, #Vietnam War, #Political Science, #General, #Asia, #Southeast Asia

II

THE KOREAN ARMISTICE, SIGNED ON JULY 27, HAD A DEVASTATING

effect on French thinking, causing a further slackening of the will to continue the fight. Marc Jacquet, the minister for the Associated States, told British officials a few days later that his compatriots were nonplussed: They saw the United States securing a truce in Korea and Britain trading with China and could not understand why their allies should expect them to continue a war in Indochina in which there was no longer a direct French interest. France, he said, wanted the future Korea peace conference extended to cover also Indochina and sought Britain’s help in that regard. He added that American aid for the French war effort was insufficient and speculated that Laniel’s government was the last that would continue the struggle.

14

Bernard B. Fall, a French-raised World War II veteran who would in time become one of the most astute analysts of both the French and American wars, and who would be killed while accompanying U.S. Marines on a mission near Hue in early 1967, saw firsthand the effect of the Korean truce as he toured Vietnam in 1953 in order to conduct field research for his Syracuse University doctoral dissertation. Born into a Jewish merchant family in Vienna in 1926, Fall lost both parents at the hands of the Nazis and joined the French underground in November 1942, at age sixteen. As a

maquisard

he soon got a taste of what it meant to fight a guerrilla war against an occupying force. Later, he saw action in the First French Army under de Lattre before being shifted—thanks to his fluency in German—to the French Army’s intelligence service. A stint as a researcher for the Nuremberg War Crimes Tribunal followed, whereupon Fall resumed his studies, first at the University of Paris and then in Munich. In 1951 he arrived in the United States, the recipient of a Fulbright fellowship to pursue graduate work at Syracuse. During a summer seminar in Washington in 1952, Fall’s instructor encouraged him to pursue research on the Indochina struggle, about which little scholarship had as yet been produced.

Fall took up the challenge with zest. He recalled in an interview in 1966: “By pure accident, one sunny day in Washington, D.C., of all places, in 1952, I got interested in Viet-Nam and it’s been sort of a bad love affair ever since.”

15

On May 16, 1953, Fall arrived in Hanoi, carrying a military-style duffel bag and with his precious Leica camera and a new shortwave radio slung over his shoulder. Granted special access as a former French army officer, Fall accompanied units on combat operations, attended lunches and dinners with officers, and kept his eyes and ears open. The signing of the Korean armistice, he later wrote, “brought a wave of exasperation and hopelessness to the senior commanders that—though hidden to outsiders—was nevertheless obvious.” For no longer could it be said that France was fighting one front of a two-front war, necessary for the defense of the West. Washington had broken the deal: It had agreed to a separate peace in Asia. And now the Chinese, being no longer preoccupied in Korea, could turn their focus southward. About Navarre, meanwhile, Fall heard mostly complaints—he was timid and uncommunicative, many in the officer corps said, disliked even by his own staff—and few commanders had much good to say about the fighting abilities of Bao Dai’s Vietnamese Nationalist Army.

16

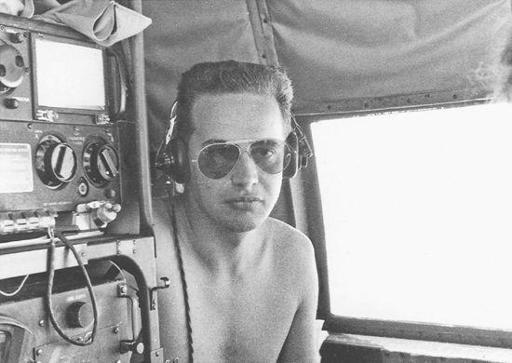

BERNARD FALL ON A SUPPLY DROP MISSION WITH FRENCH UNION FORCES, 1953.

(photo credit 15.1)

Fall sought to understand the security situation inside the Red River Delta. A French officer assured him that defenses were strong: “We are going to deny the Communists access to the eight million people in this Delta and the three million tons of rice, and will eventually starve them out and deny them access to the population.” Did the Viet Minh hold any areas in the delta? Fall asked. “Yes,” the officer replied, pointing to his map, “they hold those little blue blotches, 1, 2, 3, 4, and a little one over here.” How did he know? “It is simple, when we go there we get shot at; that’s how we know.”

17

Suspicious after hearing Vietnamese friends laugh mockingly at the officer’s claims—in their native villages, all the village chiefs were Viet Minh, whatever they told the French—Fall decided to study village tax rolls. These showed conclusively that most of the delta had not paid taxes for years. If the villages were contributing revenues to anyone, it was not to the French-backed government. Equally revealing was the teacher-assignment data: In a school system where teachers were designated by the central government, these same villages were not being assigned teachers from Hanoi. Fall produced his own maps that showed a picture of control “frighteningly different” from what French authorities were reporting. He concluded that the Viet Minh dominated 70 percent of the delta inside the French perimeter—more or less every part of it except Hanoi, Haiphong, and the other large garrison areas.

18

He wrote home of one excursion in the delta, in which his unit passed an artillery convoy and then passed through an “ominously calm” village. “A few miles further, all of a sudden [we] heard the harsh staccato of automatic weapons, then some more of the same, and a few minutes later, the heavy booms of gunfire. The artillery convoy had been ambushed in the village through which we had passed.” Fall’s unit had been spared because the Viet Minh were waiting for bigger game. “The whole thing was a matter of sheer, unforeseeable luck, because for a while we had toyed with the idea of staying with the convoy for more protection.” The convoy too was fortunate, Fall continued, losing only one dead and a few wounded, but the overall situation was perilous. “In the south today, a train blew up on a bridge and fell into a ravine.… Situation is not so hot right now.”

19

A British officer reached a similar conclusion after accompanying a French unit on a sweep of the delta a few miles south of Hanoi. He wrote of seeing an “innocent looking village” mortared and shelled by tanks and artillery for two hours, and then joining the French troops as they proceeded carefully into the town. A captured villager, presumably Viet Minh, pointed to a pile of debris in the center of the village and said it hid the entrance to a tunnel.

The large heap is quickly swept away and the Moroccans vigorously set-to with their spades. After a quarter of an hour’s digging the tunnel is found far beneath the ground. Two hand grenades are then almost daintily dropped within; after the smoke from the explosion has almost blown away, a tiny head appears above the ground and then another. Seemingly from the depths of the earth ten muddy-looking individuals emerge. They are arrested and a little Moroccan soldier with a cocky smile prepares to descend with a torch to look for the weapons which are bound to be there. But he does not get far. It seems impossible but there are still more communists below. A grenade is hurled at him from the darkness and after an ear-splitting explosion the poor screaming wretch is extracted with both his legs shattered. However, after a few more acts of persuasion the remaining two come up. “Who threw the grenade?” the officer shouts at them. The more timid looking of the two points to his partner who when asked confesses to the deed without the least sign of concern. “Where are the arms?” he is asked but he only shakes his head. The Moroccans gladly shoot him but the prisoners are unmoved by the execution and do not even turn their heads away. And when faced with the same question and the same threat they refuse to answer.

“What is it that they have that we don’t have?” the Briton plaintively asked himself, with reference to the villagers and their dedication to Ho Chi Minh. “No doubt [the French] found the weapons but there were plenty of others they did not find. When I left the village all was quiet except for the odd mine going off. Probably the same little drama was going on in all the villages. The following day the troops would leave the area. The Viet Minh would emerge from the many undiscovered tunnels and set to work and rebuild their defences. And next year all these little scenes will be repeated.”

20

A frustrated French intelligence colonel said at about the same time: “As long as the village populations are against us, we’ll just be treading water.”

21

III

JOURNALISTS TOO EXPERIENCED THE WAR UP CLOSE, AS THEY HAD

since the shooting started seven years earlier, though not all of them got as close to the action as Bernard Fall and the British officer did. The terrace bar at the Continental in Saigon remained the rendezvous point, where they discussed and debated the pressing questions: Would the taciturn Navarre inspire his troops and turn the tide? Would America step up her involvement in the war, perhaps to the point of sending troops? Would China intervene? Would the French (with Washington’s help) be able to keep the non-Communist nationalists in Vietnam in check? Would Laniel and Bidault seek direct negotiations with Ho?

No piece of reporting that summer received more attention than a devastating photographic essay in

Life

in August. “Indochina, All But Lost,” read the magazine cover, and the article, by Dennis Duncan, depicted a lethargic and fading French war effort. “It is a year when ineffective French tactics, and the ebbing of French will, make it seem that Indochina is lost to the non-communist world,” Duncan wrote. “Staff officers keep hours that would delight a banker … [and] the troops, following the example of their commanders, take long siestas.” U.S. aid, meanwhile, does not reach its intended recipients, because of the French practice of appointing Indochinese officials on the basis of their political affiliations rather than their competence. As a result, “in the background of this war is a society that has become corrupt.” Millions cast their lot with the Viet Minh not out of attachment to Communism but out of frustration with the lack of strong nationalist alternatives. An editorial in the same issue endorsed Duncan’s findings and accused Paris of pursuing “sophisticated defeatism,” even as it called victory “entirely feasible” and advocated more U.S. support in the war. Bidault, well aware of

Life

’s huge circulation in the United States, was outraged by Duncan’s claims and threatened to have the magazine pulled from Parisian store shelves. He also instructed officers at the embassy in Washington to register a complaint.

22

C. D. Jackson, a Time Inc. senior executive and editor who now served as an adviser to Eisenhower on Cold War strategy, fumed that Duncan’s spread furnished “invaluable documentation to those who want to pull out” of Indochina.

Life

’s publisher and editor-in-chief, Henry Luce, agreed. He had been away in Rome when a senior editor signed off on the article, and he furiously castigated Duncan as a “Rover Boy” who had “fouled up basic policy.”

23

On Luce’s orders, the magazine ran a rejoinder in September titled “France Is Fighting the Good Fight.” This was the prevailing theme also in Luce’s other publication,

Time

. Issue after issue in the spring and summer, while acknowledging setbacks and problems in the war effort, gave readers the impression that the trends pointed in the right direction, that the Franco-American partnership functioned smoothly like a well-oiled machine, and that the “Reds” were on the ropes. Never mind that several of the cables coming in to Time Inc.’s editorial offices from correspondents offered a much different picture, one showing a faltering war effort and expanding Viet Minh reach.

24

A

Time

cover story on Navarre in September was a perfect counterpoint to the

Life

photographic essay. This one lauded the “quiet but steely, cultured but tough” general’s conception of his role and applauded his early actions in the field. (Among them: Operation Hirondelle [Swallow], an airborne raid on enemy supply depots around Lang Son in July that involved two thousand paratroops supported by ten B-26 bombers and fifty-six Bearcat fighters. Numerous depots were destroyed, and the retreat to French lines, covering fifty miles and in crushing heat, took place without incident.) Navarre, the magazine gushed, was “a master of assembling bits and pieces into a pattern and molding the pattern into plans.” The article spoke of a “new spirit and optimism” among soldiers “who must fight the ugly war” in Vietnam, and it concluded by quoting an unnamed observer, whose phrasing would come back to haunt both the French and the Americans in later years: “A year ago none of us could see victory.… Now we can see it clearly—like light at the end of a tunnel.”

25

The two magazines did have that in common: Victory in Vietnam, both said, was “entirely feasible.”

Life

may have been downbeat about the outlook, but it put the blame squarely on French civilian and military leaders for, in effect, giving up just as victory was near. The gulf between the two Luce journals was in this respect much smaller than a quick skimming would suggest. In other press assessments that summer, the same phenomenon could be observed: Some saw the glass as half-full, some as half-empty, but very few saw it as dry or nearly dry. If defeat occurred, principal blame would lie with France, for her unwillingness either to expend more of her human and material resources to fight the war, or to grant the Indochinese people real independence.

The New York Times

, for example, was straightforwardly hawkish, insisting that the defense of Indochina was vital “not merely to France but to the whole of the free world.” If Indochina fell, the editors warned, the way would be open to Thailand, Malaya, Burma, and eventually Indonesia, India, and the Philippines.

26