Embers of War (61 page)

Authors: Fredrik Logevall

Tags: #History, #Military, #Vietnam War, #Political Science, #General, #Asia, #Southeast Asia

To many observers, Nguyen Van Tam seemed a pawn in French hands. A former lawyer and schoolteacher with a gray-streaked crew cut and a preference for white sharkskin suits, the fifty-eight-year-old had been born into a family of small merchants and had been educated in France. Seemingly indefatigable, he rose early and often worked past midnight and in his spare time wrote poetry. His hatred of the Viet Minh ran deep—he had had a hand in putting down Communist insurrections prior to and during World War II, and two of his sons were killed by Giap’s forces in 1946. Another son now served as VNA chief of staff. Glancing at a map, Tam told an American journalist: “The most important thing is winning the village populations over to the cause. Our nationalist fervor has got to match the Viet Minh’s, and once we take over from the French, Ho Chi Minh could well be forced into making a deal on our terms.”

36

To underlings, however, Tam always stressed the need to be patient and to not press the French too hard, too fast.

In October, Bao Dai, in an effort to increase pressure on the French, convened a three-day “National Congress,” and invited representatives (all chosen by Bao Dai) of all the significant religious and political factions outside the Viet Minh. This included the Hoa Hao, Cao Dai, and Binh Xuyen politico-religious sects and their affiliated parties. Going considerably further than Bao Dai wanted (thereby showing his weakness, even within anti–Viet Minh circles), the congress declared that all treaties with France be approved by a national assembly, to be elected by universal suffrage, and it passed a resolution refusing to join the French Union. Independence should be complete, proponents said, with no Vietnamese membership in any French-dominated commonwealth.

The delegates held their breath. They needed backing in high places, they knew, one place in particular. “Rightly or wrongly,” one delegate recalled, “we had invested substantial hopes in the American connection. And these hopes had been encouraged, not officially but through a series of informal contacts with the USIA, the CIA, and embassy personnel.”

37

But when they sought U.S. backing for the resolution, its sponsors found none. On the contrary, after the vote Ambassador Donald Heath summoned several key delegates, including Bao Dai’s cousin Prince Buu Loc, to his residence and castigated them for adopting a measure that could only hurt the fight against Ho Chi Minh. The United States supported Vietnam and favored independence, he said, but it was also allied to France. The resolution went too far and must be softened. Bao Dai, summoned to Paris from his perch on the Riviera to explain the congress’s action, agreed. The following day a new, milder version was passed, this one stating that Vietnam would not be part of the French Union “in its present form.”

38

Heath did not come away impressed, stressing in his report to Washington the delegates’ ”emotional, irresponsible nationalism”: “It was apparent that [the] majority of the delegates had honestly no idea of [the] import of [the] language in [the] resolution they had just passed.” And in another cable: “It is a matter of extraordinary difficulty to convey [the] degree of naiveté and childlike belief that no matter what defamatory language they use, the Vietnamese will still be safeguarded from [the] lethal Communist enemy of France and [the] United States.”

39

In Paris, the reaction to the congress was even more caustic, as newspapers and politicians of various stripes demanded to know what France was fighting for in Indochina. Ho Chi Minh and his Communists were evidently not the only foes. “Let them stew in their own juice,” President Vincent Auriol thundered. “We’ll withdraw the expeditionary force.” Prime Minister Joseph Laniel said France had “no reason to prolong her sacrifices if the very people for whom they are being made disdain those sacrifices and betray them,” a remark widely seen to be advocating early negotiations with Ho. Meanwhile, Paul Reynaud and Édouard Daladier, together with former colonial governor of Indochina Albert Sarraut, called for a full-fledged reevaluation of policy, while in the National Assembly the clamor for pulling up stakes and getting out of Indochina grew louder than ever before. Just how to manage the withdrawal remained a source of friction: The right sought to settle the conflict through a great-power initiative (perhaps including China) covering the whole of Southeast Asia, while the left insisted on the need for direct talks with the Viet Minh.

“What aim has this war still got?” asked Alain Savary, a young Socialist widely acclaimed for his intellectual brilliance. “It’s no longer even a question of defending the principle of the French Union. To fight against Communism? France is alone.… Peace will not wait, it must be actively sought. You can talk to Moscow, Peking, London, and Washington, but this will not help you deal with the real issue. The only thing that will lead to an armistice is negotiation with Ho Chi Minh.”

40

Intellectuals too increasingly clamored for an end to the war. Many had rallied around the cause of Henri Martin, a Communist activist who served in the French Navy in Indochina and witnessed the violent clash in Haiphong in November 1946. Martin returned to France determined to agitate against the war. In July 1949 he began distributing political tracts to new recruits at the Toulon naval dockyard, urging them to oppose the conflict. Arrested in 1950 and tried on charges of demoralizing the army, Martin was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison. But his case continued to attract attention and supporters, not least Jean-Paul Sartre, who went to press in late 1953 with

L’Affaire Henri Martin

. By the time the book appeared, Martin had been discreetly released at the order of President Auriol.

Portentously, a perceptible anti-Americanism crept into the discourse, as commentators noted that, with the end of the fighting in Korea, France was the only Western nation shedding blood on a major scale to fight Communism. Why, critics asked, did Washington reserve for itself a course of action—negotiations, leading to a political solution—it denied to its allies? And why, some asked (especially on the right), did these self-righteous Americans feel free to lecture France on how to treat dependent peoples, given their discrimination against Negroes within America’s own borders? The signing of the new U.S. aid agreement in Paris elicited little applause but numerous complaints about the division of labor in Vietnam. “One of the parties brings dollars, while the other makes a gift of its blood and its sons,” Daladier acidly remarked, to wide acclaim.

41

The Eisenhower administration brushed off the criticism, but it looked again for ways to keep its allies in Indochina focused on the task of winning the struggle. To the Paris government, it insisted that seven years of war had not been in vain, that her cause was both just and essential, and that negotiations should be avoided until France and the West could dictate the terms. To the non-Communist nationalist groups, it preached the message that the continued presence of the French Expeditionary Corps was essential to victory. (Subtext: The VNA by itself would get crushed in no time.) Said Heath in a speech on October 24: “There is only France who can make this military contribution at this vital moment which the destinies of the free world have now reached.… I have not the slightest doubt of the final victory of the Vietnamese National Army in unity with the noble military effort being made by the expeditionary corps of the French Union.”

42

VI

SO EAGER WAS THE WHITE HOUSE TO GET THESE POINTS ACROSS

that it dispatched a special messenger to Indochina to articulate them. At midday on October 31, Vice President Richard Nixon, accompanied by his wife, Pat, a few staffers and Secret Service agents, and a handful of reporters, landed in Saigon. The group had spent the previous day in Cambodia, where Nixon had met King Norodom Sihanouk and Prime Minister Penn Nouth. The arrival in Saigon was preceded by a sudden squall that, sweeping across the tarmac in front of the taxiing plane, soaked both the honor guard and the reception committee. Nixon, his enthusiasm undamped, emerged and delivered a short impromptu statement, whereupon he was whisked away to meetings with Nguyen Van Tam and Henri Navarre.

43

That evening Ambassador Heath hosted a dinner for the visitors at the Majestic Hotel, and in the days that followed Nixon traveled to Dalat to meet with Bao Dai, to Laos for a session with Prince Souvanna Phouma, and to Hanoi, where High Commissioner Maurice Dejean presided over a formal dinner—complete with “starched linen napkins, sparkling crystal goblets, and silver candelabra”—and where Nixon visited a French garrison in the company of Navarre and the commander of French forces in Tonkin, General René Cogny. Outfitted with battle fatigues and a helmet, Nixon rode in a convoy of American-supplied jeeps to a hot spot north of Hanoi, where he watched an artillery barrage.

44

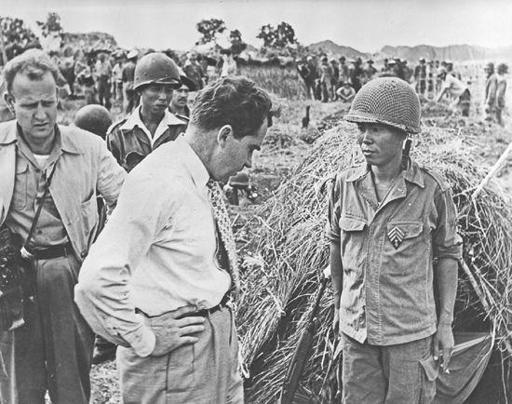

VICE PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON TRIES TO CHAT UP A SOLDIER IN THE VIETNAMESE NATIONAL ARMY AT A BASE NEAR DONG GIAO, NORTHEAST OF HANOI, IN EARLY NOVEMBER 1953.

(photo credit 15.2)

The hectic schedule left some in the entourage exhausted, but Nixon reveled in the fast pace, seemingly gaining in energy with each passing day. In speech after speech, he made the same basic points: that the defeat of Communism in Indochina was essential to the safety of the free world; that it was only in union with France that Vietnam could—and would—achieve her aims; and that no negotiated solution should be sought. “It is easy,” he said in Dalat, “in the name of nationalism and independence to call for the immediate withdrawal of the French Republic. At first glance this meets with popular favor, but those who call for such a step must also know that, if it were taken, it would mean not independence or liberty but complete domination by a foreign power.” In Hanoi, he declared himself convinced that all differences between France and the State of Vietnam could easily be solved, and added: “We must admit that in no circumstances can we negotiate a peace which would deliver into slavery the peoples whose will is to remain free, and we must know that by a close union of our efforts, this struggle will end in victory.… The tide of aggression has reached its peak and has finally begun to recede. The foundation for decisive victory has been laid.”

45

And with that, Nixon and his party were off from Hanoi, bound for home. No one could know then that nineteen years later, as president of the United States, Nixon would send B-52s to hit the city during the Christmas period in a massive and highly controversial air offensive. But what was amply evident even now, exactly a year after the Eisenhower-Nixon team’s election victory, was the administration’s determination to win in Vietnam, to keep the French fighting, and to rein in the Saigon nationalist groups. Any notion of cultivating a Third Force, one in between the Communists and the French, seemed to have vanished. Said an obviously impressed British diplomat to his superiors in London: “By this constant reiteration that the one immediate goal was the defeat of the enemy and that this must be done in union with France, Mr. Nixon has, I am sure, done something to bring the Vietnamese back to reality after pipe dreams of the National Congress.”

46

Nixon’s confident pronouncements masked deep private chagrin. The Navarre Plan was sound and could succeed by 1955 as planned, he told the National Security Council a few weeks later, but the administration should not count on it. The Communists had a sense of history, they had determination and skill, and they believed time was on their side. Bao Dai and the non-Communist groups were weak entities, while in the French High Command there was legitimate fear that Paris would seek premature negotiations. “There is a definite need to stiffen the French at home,” Nixon said, because Washington’s recent aid increase, though essential, would do little good if Navarre did not have full support from the metropole. For the French commander Nixon offered mostly praise, but he lamented Navarre’s failure to utilize the VNA effectively and his reluctance to accept American advice regarding how the native army should be trained.

47

Even here, though, the vice president was sympathetic to the French dilemma. He told a group of State Department officers:

Deep down I sense that Navarre, and Cogny, the Field Commander, and the other field commanders I talked to on the scene at the present time have very little faith in the ability of the Vietnamese to fight separately in independent units which don’t have French noncoms. That may be a cover for the fact that the French naturally have a reluctance to build up a strong independent Vietnamese army because they know that once that is done and once the Vietnamese are able to handle the problem themselves, that despite all the fine talk about the independence within the French Union—when that time comes, the Vietnamese will kick out the French.