Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815 (115 page)

Read Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815 Online

Authors: Gordon S. Wood

Tags: ##genre

Although the Madison government claimed that this ambiguous victory had brought peace to the Northwest frontier, Westerners in the region knew differently and stressed their continued vulnerability to Indian attacks, especially if the Indians were supported by the British in Canada. It was not surprising therefore that an invasion of Canada became central to America’s war plans in 1812. Not only would such an invasion help to pressure the British to make peace, but it would end their influence with the Northwestern Indians once and for all and bring about Britain’s full compliance with the peace treaty of 1783. Although Madison’s government always denied that it intended to annex Canada, it had no doubt, as Secretary of State Monroe told the British government in June 1812, that once the United States forces occupied the British provinces, it would be “difficult to relinquish territory which had been conquered.”

39

Besides the possibility of removing the Indian threat, the Republicans had other reasons for wanting to take Canada from Great Britain: they thought it was already filled with Americans. Many Loyalists who had fled the Revolution lived in Canada, and since the 1790s perhaps fifty thousand American citizens, many frustrated with the archaic system of landholding in New York, had left the United States in search of cheap land and had moved into the southwest corner of Lower Canada (present-day Quebec) and into Upper Canada (present-day Ontario, and southwest of Lower Canada). With so many Americans willing to leave the United States for cheap land, it is no wonder the Republicans were worried about the strength of their countrymen’s attachment to the nation. Canada was becoming less a sterile snow-clad wilderness and more a collection of substantial British colonies that the United States could no longer ignore. Smuggling over the northern border had undermined the embargo and weakened other Republican efforts to restrict trade with Britain. Moreover, evidence mounted that Canada was becoming a major source of supply for both the British West Indies and the mother country itself, especially for timber. With the development of Canada freeing the British Empire from its vulnerability to American economic restrictions, President Madison was bound to be concerned about Canada.

A

LTHOUGH GROWING

, Canada seemed especially vulnerable to an American invasion. It had only about five hundred thousand people compared

to the nearly eight million in the United States, and it was still economically rather undeveloped. Since two-thirds of the people of Lower Canada were of French descent, their loyalty to the British crown was doubtful. Upper Canada, that is, the Niagara area, which was the most likely site of an invasion, had a white population of only seventy-seven thousand, of whom one third or more were American in origin and perhaps sympathy.

40

In mid-July 1812 Governor Daniel Tompkins of New York was sure that half the militias of both Lower and Upper Canada “would join our standard.”

41

Since the Canadian frontier from Quebec to Mackinac Island at the junction of Lake Huron and Lake Michigan stretched well over a thousand miles, it seemed difficult to defend. Jefferson expressed the confidence of many Republicans in 1812 when he predicted the invasion of Canada would be “a mere matter of marching.”

42

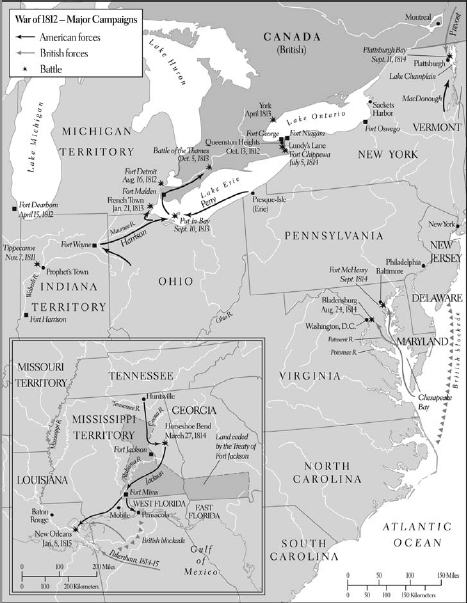

The plan for invasion involved a three-pronged attack on the areas of Detroit, Niagara, and Montreal. Although Montreal was supposedly the main objective, the unwillingness of Massachusetts and Connecticut to supply militia for the assault on Montreal made the western attack on the Detroit frontier seem more feasible. William Hull and his two thousand troops were to march from Ohio to take the British Fort Malden south of Detroit. Hull’s officers, who jealously quarreled over precedence with one another, had little confidence in their commander, dismissing him as old and indecisive even before the force set out. When Hull’s troops reached the Canadian border in July 1812, two hundred members of the Ohio militia refused to cross over into Canada, claiming that they were a defensive force only and could not fight outside of the United States.

Hull hoped for little or no resistance. He urged the people of Canada to remain in their homes or join the American cause; perhaps as many as five hundred did in fact desert the Canadian militia. Although Fort Malden was only lightly defended, Hull was worried about his supply lines and kept delaying his attack. When he learned that Fort Mackinac, at the junction of Lake Huron and Lake Michigan, had surrendered to British forces on July 17, he became more apprehensive, fearing that Indians from the north would now descend on him. Without Fort Mackinac in American hands, Hull believed that Fort Dearborn at the present site of Chicago could not be held, and he ordered its evacuation, which eventually took place on August 15. On August 6, 1812, Hull finally ordered an attack on Fort Malden, only to cancel it the next day when he heard that British regulars were on their way to the threatened fort. When Hull next decided to retreat to Detroit, many of the militia officers wanted to remove him from command, but the regular officers stopped the mutiny.

The British commander, Major General Isaac Brock, the governor of Upper Canada, took advantage of Hull’s timidity and mobilized his troops to march on Detroit. His force included a mixture of two hundred fifty regulars, four hundred militia, and about six hundred Indians under Tecumseh’s leadership. Capitalizing on Hull’s dread of Indian atrocities, Brock arranged to have a bogus document fall into American hands in order to feign having more Indian troops than he actually had. Hull, paralyzed with fear that he was cut off from his supplies and faced an overwhelming force, including Indians that might massacre the women and children in the Detroit fort, surrendered on August 16, 1812, without firing a shot. After taking Detroit, Brock annexed the whole territory of Michigan and made it part of the dominion of His Majesty George III.

Hull’s surrender of Detroit shocked everyone, and rather unfairly he alone was held responsible for the disaster. Hull was eventually courtmartialed for cowardice and neglect of duty and was sentenced to death, with a recommendation of mercy because of his Revolutionary War service and advanced age. Madison accepted this recommendation and commuted Hull’s punishment to dismissal from the army. With the loss of the forts at Detroit, Mackinac, and Dearborn, the whole Northwest lay open to British invasion and Indian raids.

Although the administration wanted someone else to command the Western forces, it was compelled by local pressure, especially from Kentucky, to appoint William Henry Harrison, the alleged hero of Tippecanoe, as the commanding general to replace Hull. In the winter of 1812–1813 Harrison sent a detachment of eight hundred fifty troops to protect settlers at Frenchtown eighteen miles southwest of Malden (now Monroe, Michigan). Attacked on January 21, 1813, at the River Raisin by a force of about twelve hundred British and Indians, the outnumbered Americans surrendered. When the British troops had left with the American prisoners who could walk, the Indians allied to the British became drunk and massacred dozens of the wounded prisoners who had been left behind. “Remember the Raisin” became an American rallying cry throughout the Northwest.

The invasions of the eastern portions of Canada were no more successful. Although Major General Henry Dearborn was presumably responsible for the area from Niagara eastward to New England, he scarcely seems to have comprehended what was expected of him. As customs collector for Boston, he was reluctant to leave New England. Although he had helped design the invasion plan and had received explicit instructions, he nevertheless wondered to the secretary of war about “who was to have command of the operations in Upper Canada; I take it for granted,”

he said, “that my command does not extend to that distant quarter.” Instead of launching an attack on Montreal from Albany and thus relieving some of the pressure on Hull in the West, Dearborn spent months in New England trying to recruit men and build coastal defenses.

43

When Dearborn seemed confused about his responsibilities for the Niagara campaign, Governor Daniel Tompkins of New York took matters into his own hands and appointed Stephen Van Rensselaer commander-in-chief of the New York militia. Although Van Rensselaer had no military experience, he was a Federalist, and Tomkins thought this appointment might ease some of the Federalist opposition to the war. In October 1812 Van Rensselaer with four thousand troops successfully attacked Queenston Heights on the British side of the Niagara River, and in the process killed the heroic General Brock, who had returned from Detroit to take command of the British defense. When Van Rensselaer sought to send the New York militia to reinforce the troops in Queenston Heights, they, like the militia in the West, developed constitutional scruples and refused to leave the country. Consequently, the American force, numbering about a thousand men, was soon overwhelmed by British reinforcements and on October 13, 1812, was forced to surrender. The Battle of Queenston Heights became a rich site of memory for the victorious Canadians and an important stimulus for their own emerging nationalism. Brock’s death turned him into a cult figure in Upper Canada, and numerous streets, towns, and a university were named after him.

44

In the East, General Dearborn had not yet begun to move against Canada. Only in November 1812, after prodding by the exasperated secretary of war, did Dearborn’s army, numbering between six and eight thousand men, set out from Albany northward toward Canada. Again the state militia refused to cross the border, and Dearborn abandoned his feeble attempt at an invasion. His entire venture, recalled a contemporary, was a “miscarriage without even the heroism of disaster.”

45

The three-pronged American campaign against Canada in 1812 had been a complete failure. What was worse, the failure was due less to the superiority of the Canadian resistance and more to the inability of the United States to recruit and manage its armies.

T

HE WAR AT SEA IN

1812 helped to take some of the sting out of that failure. Although the Republicans in Congress had decided in January 1812 not to build any new ships, seventeen ships, including seven

frigates, still survived from the naval buildup during the Quasi-War with France in the late 1790 s. The U.S. Navy had no large ships of the line that carried seventy-four guns, but three of the frigates, the USS

Constitution

, the USS

President

, and the USS

United States

, had forty-four guns and were bigger and sturdier than most other foreign frigates. Although Britain had hundreds of vessels, they were spread about the world. In 1812 Britain had only one ship of the line and nine frigates operating out of its North American stations at Halifax and Newfoundland.

The

Constitution

, captained by Isaac Hull, thirty-nine-year-old nephew of General William Hull, was the first American warship to acquire fame in the war. After escaping from a British squadron in July 1812 in one of the longest and most exciting chases in naval history, the

Constitution

on August 19 defeated HMS

Guerrière

, a thirty-eight-gun frigate under the command of Captain Richard Dacres, who earlier had contemptuously challenged the American naval commanders to frigate-to-frigate duels at sea. When during the engagement, which took place 750 miles east of Boston, a British broadside bounced harmlessly off the

Constitution

’s hull, one of the crew supposedly exclaimed that “her sides are made of iron,” and the legend of “Old Ironsides” was born. The London

Times

was stunned by the American victory. Since “never before in the history of the world did an English frigate strike to an American,” the paper predicted that the victory was likely to make the Americans “insolent and confident.”

46

As a consequence of the

Constitution

’s victory, Madison’s government gave up its original idea of keeping the navy bottled up in the harbors as floating batteries. Instead, America’s ships were divided into three squadrons and ordered to fan out over the central Atlantic trade routes and to take advantage of every opportunity to meet and destroy the enemy. In October 1812 the

United States

under the command of thirty-three-year-old Stephen Decatur, the hero of Tripoli in 1804, showed brilliant seamanship in defeating and capturing HMS

Macedonian

six hundred miles west of the Canary Islands. A prize crew sailed the

Macedonian

, which was only two years old, across the ocean—a very risky venture—and into the harbor of Newport, Rhode Island. Since the

Macedonian

was the first and only British frigate ever brought into an American port as a prize of war, its capture made Decatur a hero all over again. The officers and crew of the

United States

received $300,000 in prize money, the largest award made for the capture of a single ship during the war.

47