Empire of Sin (35 page)

Authors: Gary Krist

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #South (AL; AR; FL; GA; KY; LA; MS; NC; SC; TN; VA; WV), #True Crime, #Murder, #Serial Killers, #Social Science, #Sociology, #Urban

But when an opportunity arose to play outside the city, Bechet grabbed it. In late 1916, pianist

Clarence Williams put together a traveling vaudeville troupe; Bechet signed on to play in a quartet that would accompany comedy and vocal routines (with the musicians sometimes doubling as actors in the skits). The company set out with hopes of touring widely throughout the country, but ran out of bookings once they reached Galveston, Texas. Bechet and pianist Louis Wade, still eager to see the world beyond New Orleans, joined a traveling carnival for a time—until one day they woke up in a town called Plantersville and discovered that the whole company had moved on without them. “

When we went down to the carnival ground in the morning, it was just an empty field,” Bechet recalled. “I learned later there had been some sheriff who had come around and told them they had to clear out. And so there we were.”

A few nights later, Sidney was asked to play for a dance in town. He was reluctant at first; the dance would end late, and walking back to his lodgings after midnight would be a dangerous thing for a black stranger to do in a small Southern town. But one of the organizers promised to find someone local to walk him home, so Sidney agreed to do it. Unfortunately, however, his escort proved to be a drunken white man whose idea of a joke was taunting his young companion and scaring him half to death. As they were passing through a dark and lonely rail yard, the man disappeared into the blackness and then jumped out at Sidney from behind a pile of railroad ties. Sidney, who had picked up a slab of wood for protection, swung it at him before he could think twice. “

I felt that stick hit and I knew I’d fixed him good,” Bechet wrote. “He made a grab at me and I swung that stick again, and then I didn’t know what I was doing.” Panicking, Bechet started running away along the dark railroad tracks as fast as he could. “I kept running for a mile, maybe a mile and a half, until I had to catch my breath.”

Now he was truly frightened. In these parts, he knew, a black man who assaulted a white man could not expect to live long, no matter how justified his action. So he hopped on the first freight train that passed, hoping it would take him back to Galveston, where one of his older brothers was living at the time. But his trouble didn’t end there. A brakeman who had seen him board came over the top of one of the boxcars and began swinging his club at Bechet, trying to knock him off the ladder he clung to. But Sidney would not let go. “He could have killed me,” he recalled, “but I’d have died holding on to that bar.”

Eventually—perhaps after seeing how young Bechet was—the brakeman gave up trying to dislodge him from the ladder. He came down between the cars and made the young man climb to the top of the ladder. Then he marched him back along the swaying boxcar roofs to the caboose. Sidney was expecting trouble, but the brakeman had turned friendly now; he and the other crewmen in the caboose talked about having Bechet arrested at the next stop, but he could tell that they were just teasing. He also found out that the train was headed straight to Galveston, just as he’d hoped. “That kind of changing around, the way luck goes faster than you can figure it,” he later wrote, “it just won’t be understood.”

When the brakeman saw the clarinet case tucked into Sidney’s waistband, he asked to hear him play, and Sidney complied. “If I had any doubt before [about the brakeman’s good intentions], I knew it was gone when I saw him sitting there listening to the music. It was noisy in that caboose, but the clarinet had a tone that cut through those train sounds, and I could tell that these men, they were enjoying the music real good.”

And so he played for them all the way to Galveston, rocking along in the caboose through the chilly Texas night. When they finally reached the station, the brakeman even pulled him aside and told him how to get away from the train yards without running into the resident detective, who would be on the lookout for tramps.

For the next several weeks, Sidney lived with his brother Joe in Galveston. They’d play some engagements together at local joints, returning home early every night. But Sidney, being Sidney, could behave only for so long. One night when his brother wasn’t with him, he stayed out late, hopping from saloon to saloon as the hours passed unnoticed. In one place he met a Mexican guitarist who spoke little English but “

could play the hell out of that guitar.” They jammed together for a time, and then, at the end of the night, when Sidney learned that the man had no money and no place to stay, he decided to take him home to his brother’s house.

It was apparently time for Sidney’s luck to change again. As they made their way down M Street in the early hours of the morning, they were stopped by two policemen who asked them where they were going. Sidney tried to explain that they were going to his brother’s house, which was tucked away on an alley he knew only as “M and a Half Street.” The cops just laughed, claiming that there was no such place, and carted them off to jail as suspicious characters.

It quickly turned into a nightmare. One of the detectives at the station, who had lost a hand in a shooting incident in Galveston’s Mexican ghetto, apparently held all Mexicans responsible for his misfortune and proceeded to beat Sidney’s friend until his face was an unrecognizable bloody pulp. Sidney could only watch in terror. “I was just standing there,” he recalled, “frozen up with fear, thinking they’d be doing the same to me … that it would be me lying on the floor with my face kicked in.”

In the end, they merely threw him into a cell with several other men and slammed the door behind him. They hadn’t hurt him physically. They’d even let him keep his clarinet. And that was what he turned to for comfort. “It was while I was in jail there,” he wrote, “that I played the first blues I ever played with a lot of guys singing and no other instruments, just the singing. And, oh my God, what singing that was.”

With Sidney playing along, the other men in the cell just started chanting about the hard times they’d seen. “This blues was different from anything I ever heard. Someone’s woman left town, or someone’s man, he’d gone around to another door … I could

taste

how it felt … I was seeing the chains and that gallows, feeling the tears on my own face, rejoicing in the Angel the Lord sent down for that sinner. Oh my God, that was a blues.”

For Bechet, it was a lesson about where the blues—and the blues impulse behind jazz—really came from. The singer or player of blues, he realized, “was more than just a man. He was like every man that’s been done a wrong. Inside him he’s got the memory of all the wrong that’s been done to my people … You just can’t ever forget it. There’s nothing about that night I could ever forget.”

The next morning, his brother explained to the police that there really was an M and a Half Street, and got him released from jail. (Sidney would never know what happened to his Mexican friend.) As they walked home, Joe told him that he’d just gotten a job offer to play in New Orleans again, and he wanted Sidney to come back and play with him. Sidney agreed immediately. “I hadn’t been out of New Orleans long,” he wrote, “but there never was anyone who could have been readier to go back.” Before the week was out, he was home again.

But Bechet would soon have other opportunities to escape the oppressive environment of his Southern home. Many of the jazzmen who had already left New Orleans were finding enthusiastic audiences elsewhere in the country. Freddie Keppard, for one, kept sending home

newspaper clippings from the road, full of praise from critics in places like San Francisco, New York, and Chicago. And it wasn’t just musicians who were making good elsewhere. With the economy gearing up for the coming war effort and factories losing many of their workers to the armed forces, jobs were increasingly plentiful in the industrialized cities of the North; some companies were even sending labor agents through the South to recruit black workers for their factories. The first wave of the Great Migration of African Americans had begun, and its pull would be felt by blacks across the South for decades to come.

Those who went north, moreover, now had a little money in their pockets to spend on entertainment. And spend they did, in numerous new clubs and theaters, some owned and operated by black entrepreneurs. In Northern cities, jazz could be performed with far less fear of police raids and reform efforts aimed at suppressing the music in the name of morality and white supremacy. The new sound, in fact, was exciting admiration even among certain white audiences. In 1917, a white ensemble called the Original Dixieland Jazz Band (ODJB)—made up of New Orleanians Nick LaRocca, Larry Shields, and some other players from Jack Laine’s old Reliance Brass Bands—made the

first jazz recordings for Victor in New York. Some black musicians disparaged the work of these white interlopers, who were admittedly less skilled technically and who played virtually everything so fast that they drained all of the soul out of it. Sidney Bechet, for one, didn’t think white musicians could really play jazz. “

I don’t care what you say,” he wrote in his autobiography, “it’s awful hard for a man who isn’t black to play a melody that’s come deep out of black people. It’s a question of feeling … Take a number like

Livery Stable Blues

. We’d played that before they could remember; it was something we knew about a long way back. But theirs, it was a burlesque of the blues. There wasn’t nothing serious in it anymore.”

But for white audiences, the music of the ODJB was a sensation. Their recording of “Livery Stable Blues” became wildly popular. And soon many black bands were reaping the benefits of that success. Some black groups

changed up the composition of their ensembles, eliminating the violin to emulate the ODJB lineup. They also adopted the neologism “jazz”—sometimes spelled “jass” or even “jasz” in these early years—for the music they had informally been calling “ragtime” for twenty years. Before long, black bands were recording as well, to wide popular acclaim. And 1917 was the turning point. As one historian put it: “

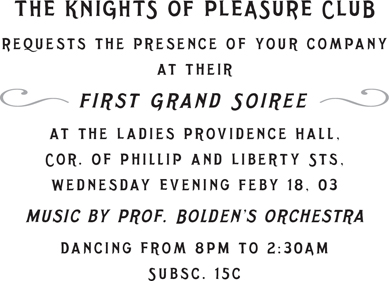

By 1917 jazz, the Southern folk music, had emerged as jazz, the profitable commodity.” Whatever its reception among the elites of its place of birth, Bolden’s new sound now belonged to the world.

I

N

New Orleans, however, the American entry into the war—and the simultaneous reinvigoration of local reform efforts against vice—was making the situation for local jazzmen increasingly dire. Not least of the troubles was the fact that many musicians now had to worry about being conscripted into the military. In July, the federal government instituted a draft lottery for all men twenty-one to thirty-one years of age. Louis Armstrong and some of the other rising players were still too young to worry, but most of the other musicians fit squarely into that age bracket, and few were enthusiastic about serving. One night, after a gig attended by Mayor Behrman’s secretary, Manuel Manetta asked him whether his and Ory’s band would have to be broken up. The secretary told him not to worry, that any band members who were married would be exempt from the draft. As Manetta later recalled: “

A lot of these guys were running wild” at the time, neglecting their marriages. “Well,” Manetta admitted, “they [soon] made up with their wives.”

The more serious problem was collateral damage from the other war—the one between reformers and the forces of vice in the city. Commissioner Newman’s moves to close the cribs, segregate Storyville, and enforce the requirements of Gay-Shattuck had taken their toll,

forcing substantial layoffs of musicians, waiters, bartenders, and prostitutes. Emboldened by these successes (and by his growing approval among the reform element), Newman next turned his sights on a zealous enforcement of the Sunday Closing Law, ordering a detail of patrolmen to adopt plainclothes and visit saloons on the Sabbath to root out violators. For Mayor Behrman, this was going too far. Using plainclothes police to “

spy on business people,” he announced, was contrary to good public policy, an inducement to distrust and an invitation to graft. Newman disagreed. “

You might just as well telephone to a burglar that you are coming to arrest him as to expect policemen in uniform to catch violations of the Sunday law,” he insisted.

But Behrman drew the line on this issue. The mayor instructed Superintendent Reynolds to discontinue the practice; Newman, who had nominal authority over the police force, issued orders for the practice to continue. After one Sunday when police had no idea whether to don their bluecoats or not, the conflict came to a head—and Behrman won. In a highly sanctimonious statement to the press, Newman announced his resignation as commissioner of public safety. “

I do not believe I could have slept another night with this thing hanging over me,” he said. “It was a violation of all my principles and moral convictions.” But he warned the Ring that public sentiment had changed in the city: “

The people of New Orleans have seen that the Sunday law can be enforced, and the brewery interests have made a bad move for themselves in this effort to reopen the city. The sentiment here is for law enforcement.”

Reformers soon had the federal government behind them as well. The war effort had raised concerns nationwide about the fitness of the country’s fighting forces; the feds were now insisting on strict enforcement of all vice laws designed to keep soldiers and sailors away from the evils of indulgence. “

Men must live straight to shoot straight,” as Navy secretary Josephus Daniels put it. That meant keeping temptation out of their path. “Keeping Fit to Fight,” a pamphlet written by the American Social Hygiene Association and distributed to all soldiers, put the matter in no uncertain terms: “

The greatest menace to the vitality and fighting vigor of any army is venereal diseases (clap and syphilis)…[and] the escape from this danger is up to the patriotism and good sense of soldiers like yourself … WOMEN WHO SOLICIT SOLDIERS FOR IMMORAL PURPOSES ARE USUALLY DISEASE SPREADERS AND FRIENDS OF THE ENEMY.”