Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World (31 page)

Read Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World Online

Authors: Nicholas Ostler

Tags: #History, #Language, #Linguistics, #Nonfiction, #V5

Linguistically, not much would have changed when the Romans unseated the Greeks in 30 BC, other than a small influx of Latin speakers, principally soldiers. But this change of government was to prove the profoundest turning point for the fate of the language: Egypt was no longer to be governed by its own kings in its own interest, but by provincial governors as a useful bread basket for Rome, and (increasingly) a destination for rich tourists.

What all the invasions had in common was the fact that they were not nomadic movements: they were military affairs conducted by well-organised armies in pursuit of commanders’ global political aims. The point in controlling Egypt was to be associated with its ancient glory, and to appropriate its present agricultural wealth. Otherwise, Egypt was to be kept true to its traditions, and so the only population movements were movements of elites, and small groups such as the Jews. Egyptian civilisation had, however, become a hollow show. There was no longer any pharaoh to hold the country through

maR ‘at

and perform the sacrifices, unless the Roman emperor happened to be visiting, and by the third century AD even this pretence had been abandoned.

The one elite activity retained by Egyptians was religion, and the language provided a link between its priests and the common people. Nevertheless, after three centuries of Roman rule even this link was to weaken. The local Christian community had grown, first in the face of Roman persecution, and then with official support, adopting Egyptian rather than Greek as its language. In this way, it provided a new focus, of a spiritual kind, for Egyptian loyalty. But its growing strength was characteristically marked with intolerance, particularly towards the ancient religion. How were the Christians to know that in destroying it, they were also pruning away the deepest roots that anchored and sustained their separate identity? By the fourth century AD, Egypt had become a Christian country whose populace spoke Egyptian, but whose administration and cultural life were conducted in Greek. It was still true that Egyptian’s one elite activity was religion, but now this was the local version of the Christian faith.

In 641, when political control moved to Arabic speakers, there was no space left for the elite activities in Greek. They soon withered, although some formal use of Greek continued for over a century. Religion was to yield much more slowly. But this was not just another political conquest: Islam, unlike Alexander and Augustus Caesar, aspired to win over all. When it did, the last motive for retaining Egyptian was removed: converts moved into a new confessional community, Arabic-speaking and cosmopolitan. Egyptian was left as the language of liturgy for those who were determined to hang on to their Christian faith, a gradually shrinking minority.

Even in hindsight, it is difficult to say whether Christianity was more of a blessing or a bane to Egyptian. It provided a strong ritual focus for the Egyptian-speaking community under Roman secular rule; but it was militant in cutting the links the language had had with its national pagan past. It provided a new synthetic identity, that of ‘Egyptian Christian’ or Copt, to replace the ancient one, an identity that was to last for many centuries, and for a small minority even until the present day. But the theological motivation for a separate Egyptian sect of Christianity, promoted as a universal faith, was nil. Egyptian was correspondingly weaker when it faced the challenging embrace of the Arabic-speaking community: what ground was there to maintain their Egyptian identity when the gods and rituals of the land of Egypt had all been long forgotten?

Ultimately, Egyptian could not sustain itself when it ceased to be a majority language in its one and only environment, the land of Egypt. The language, like the pharaonic religion, had been a symbol of Egyptian identity. Egyptian could survive a government speaking a foreign language, as long as its religion was based in Egypt. It could not survive a foreign government and a truly cosmopolitan religion, for its speakers had nothing national left as a focus for their identity. They might as well become Arab Muslims, just like all the rest.

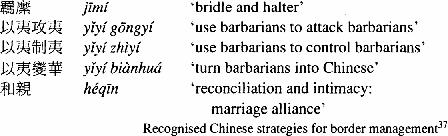

Recognised Chinese strategies for border management

37

The final decline of Egyptian can be understood as the long-term effect of losing the sense of its own centre.

After the Roman conquest, Egypt was at best a curiosity on the edge of Rome’s Mediterranean world, no longer responsible for its own destiny, but looking hopefully to the west. Four centuries later, the change of focus from Rome to Byzantium had had little impact; Egypt’s identity was sustained by its contributions to the new and growing faith of Christianity. Three centuries later still, the further shock of being incorporated into a quite different alien empire, one that was centred now to its east (in Damascus, then Baghdad), was more than its separate identity could stand. For the first and last time, Egyptian went into decline.

China has always viewed itself as being at the centre of its world, traditionally

Tiān Xià

, ‘Heaven Below’, encompassed on every side by lesser peoples, inferior in cultivation and morals. The modern word for the country,

Zhōnggŭo

, ’Central Realm’, seems to say it all. But another way of referring to the whole country is

Sìnši zhīněi

, ‘Within the Four Seas’, going back at least to Confucius. The Chinese conventionally saw themselves as living in Nine Continents within Four Seas. Each of those seas was seen as the haunt of a barbarian people, the so-called

Sìyí

, ‘The Four Yi’:

Dōng Yí Běi Dí Xī Róng Nán Mán

, ‘east the Yi, north the Di, west the Rong, south the Man’. This idea of the steppes that surround China’s heartland as seas, bizarre to anyone who looks at a modern map, had a certain reality when those steppes were populated by pastoral nomads, roaming the grassy plains to prey on the sedentary farmers who lived round the oases, the islands in this ocean. And beyond the

Sìyí

in the traditional world-view lay the

Bāhuāng

, ‘the Eight Wastes’, so it is understandable that the traditional Chinese was little tempted to explore farther abroad.

*

Within this ring of hostiles, the Chinese saw themselves at its centre, with a shared conception of civilised values, and a persistent aspiration to bring willing neighbours into their fold.

There were three features of the Chinese situation that kept their vast community not only centred but also united, socially and linguistically. The first was a

fact

about their human environment, which quite literally came with the territory that they inhabited. The second was an

institution

invented quite distinctively by the Chinese, which turned out to be remarkably persistent. And the third was the

paradoxical result

of the barbarian conquests when they came.

The fact was the periodic influx of hostile marauding nomads, speaking languages radically different to Chinese, and preying on settled Chinese farmers. This had an objective effect on the language, and a subjective effect on Chinese consciousness. Linguistically, the periodic influxes kept the northern Chinese population on the move, preventing it from settling into distinct dialect areas. But even when, as in the golden ages of the Han and the Tang, the barbarian threat was effecively countered for centuries at a time, the consciousness of barbarians at the gate still remained, naturally causing a greater sense of unity in the population. The external threat of invasion kept the Chinese focused on what they had to lose; and recurrent partial failures of the centre’s defences against it kept the north of China in flux, and so perversely maintained the cohesion of its spoken language.

The institution was the system of public examinations, persistent over thirteen centuries, where success was the key to a career in government. This meant that from a very early era China could boast a formally constituted civil service. When it was working, this had an effect on social order analogous to the influxes of invaders on the linguistic order. Both tended to reduce local groupings, and emphasise higher-level loyalties. The meritocratic civil service built loyalties to the state, and undercut the personal loyalties which, when the central government was weakening, tended to develop and split the country into the power bases of contending warlords. But it also had a further effect, bound up with the Chinese language.

The syllabus was almost entirely literary, including composition of classical poetry (introduced under the empress Wu at the end of the eighth century) and of the notorious bāgŭwén

bāgŭwén

, ‘eight-legged essays’, which rigorously elicited clear expression of the ideas from the classical texts and their application to contemporary problems. As such, it could only promote national standards for the major language in which it was conducted,

wényán

, classical Chinese.

In this sense it is fair to say that the Chinese state, outside the imperial court, was constituted as the political manifestation of the Chinese literary elite. Cai Xiang, himself a brilliant product of the system, remarked negatively in the middle of the eleventh century:

Nowadays in appointing people it can be observed that they are advanced in office mainly on the basis of their literary skills. The highest office-holders are literary men; those attending the throne are literary men; those managing fiscal matters are literary men; the chief commanders of the border defences are literary men; all the Regional Transport Commissioners are literary men; all the Prefects in the provinces are literary men.

38

Accounts of the examination system are full of caveats about the distance between its meritocratic theory and its aristocratic and plutocratic reality. It could hardly have been otherwise in an institution that lasted for over two thousand years, every so often dropped or reconstituted. Nevertheless, however unsatisfactory it may often have been for the vast number of bright individuals whom it failed to favour (all women, for example, were excluded), it was never a dead letter: it always existed as a potential means which could be resurrected or reformed to bring new talent into power and influence, a built-in agitator of the sediments of the Chinese establishment, a perpetual grain of sand in the government oyster.

Just as invasion by Altaic hordes kept northern China’s populace on the boil, so the examination system, and appointments based on it, kept the power structures open. It therefore promoted the cohesion of the body politic as a whole, with a common language whose standards were clearly defined by the examination syllabus.

The paradoxical result was the fact that although China was ultimately unable to stem the pressure from militarised pastoral nomads, and had to yield its throne to the Mongols and the Manchus, China remained Chinese. The struggle with the barbarians was, in the last analysis, lost—yet it did not matter for the future of the language, or of the culture that it conveyed. In a way, Chinese showed that it could transcend the most fundamental defeat.

Strategically, this may be characterised—in Chinese terms—as:

—

tōu liáng huàn zhùSteal the beams, change the pillars.

39