Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World (85 page)

Read Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World Online

Authors: Nicholas Ostler

Tags: #History, #Language, #Linguistics, #Nonfiction, #V5

The French Revolution ushered in a new phase of imperial wars, but with the exception of Napoleon’s somewhat romantic foray to Egypt in 1798-9, they were all waged within the continent of Europe; and they all amounted, in less than a generation, to nothing at all. Ironically, the great claims to fame of France in the early modern period, the Revolution and the reign of Napoleon, contributed little if anything to the spread of the French language, even if they sent French-speaking soldiers all over Europe.

But then, with the restoration of the monarchy in 1815, the French entered on a new bout of overseas imperialism.

†

Their motives were mixed. In one important case, France acted like ancient Rome, when in 1830 an attempt to rid the Mediterranean of pirates ended up with the full-scale invasion of Algeria, detaching what had been a province of the Ottoman empire. Still in accord with the Roman model, this was followed by an influx of settlers (

colōnī

for the Romans,

colons

for the French), in fairly large numbers: there were already 110,000 of them in 1847, and their numbers rose to just under a million in the next century.

42

But this was an exceptional case, even though it loomed largest in French conceptions of their new empire. In many other cases, French action was led by missionary compassion or zeal, as with the protectorates claimed in the Indian Ocean (

Comores

, 1840) and in the Pacific (in

les īCles de la Société

, 1843, Tahiti, 1846,

Nouvelle-Calédonie

, 1853). Similar motives, at some level, seem to have led to the expansion of French control from its ancient base in Senegal in the fifty years from 1817, training native infantry (

tirailleurs

) and priests and then taking action against malaria, and building schools and roads. It was persecution of Christian missions that gave France its justification for invading Cochin-China in 1859: by 1887 a French

Union indochinoise

controlled the whole of what is now Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos.

But these colonial acquisitions came at a time when Europeans were beginning to be highly impressed by their own technical superiority over people anywhere else in the world. Once again France began to look for explanations of its success: characteristically, it came to see itself as a power that could make a difference to the world for the better, spreading not just Catholic Christianity and respect for law, but also freemasonry, Saint-Simonian industrial policy, and in short

la civilisation franαaise.

It was easy to combine this with an ambition to do well while doing good, and so there were few reservations felt when France, and Belgium too, joined in

’la course aux colonies’

, what Britain knew as ‘the scramble for Africa’.

The French and the British were the big winners in the sheer scale of territory acquired: both empires grew massively in the last decades of the nineteenth century. The French expanded from their existing possessions in Algeria and Senegal, but they also established new bridgeheads in Côte d’Ivoire (1842) and Gabon (1843). First, from 1876 to 1885,

Afrique-Équatoriale Franαaise

(French Equatorial Africa) was carved out from the Gabon shore, including what were to become Gabon, Congo, the Central African Republic and Chad; then from 1883 to 1894

Afrique-Occidentale Française

(French West Africa) was taken from the west and south-west, comprising the modern Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire, Burkina Faso, Niger and Benin.

And the French were not the only francophones in the race. In 1877-9, Belgium’s King Léopold, adopting as his personal agent the British explorer Sir Henry Stanley, had brazenly claimed the area now known as the Congo, a claim accepted by the other European powers in 1885. Then, in 1896, the French went on to depose the queen of Madagascar, justifying their action by the immediate abolition of slavery in her old domains. And on top of it all, France was also claiming protectorates among Algeria’s neighbours along the Mediterranean coast, Tunisia in 1881, and Morocco in 1912.

By 1913, French was the language of the rulers of a good third of Africa’s land area, from the Atlas mountains on the north Atlantic to the Great Lakes of the Rift Valley. It was an expansion to compare with the adventures of Alexander, or the great Muslim jihad of the seventh century: fifty years earlier, the language had not been heard in Africa outside Algeria and Senegal.

In many ways, the French exerted themselves to be worthy of their sudden new domains, bringing roads, railways and the telegraph, scientific assaults on malaria and other tropical diseases, as well as the Christian faith, the French language, and—to a few privileged souls—an appreciation of Cartesian rationalism. They do seem to have succeeded in transmitting to their subjects a sense that the only practicable route to power and independence lay through mastery of their own skills: this kind of persuasion was one of their ideals, what they called

rayonnement

, ‘beaming’. Far more than other European empires, they struggled with the question of what their true interest in these subjects was: exploitation, assimilation, evangelisation, education or simple political association. Was it

la gloire

that France was seeking, or

sa mission civilisatrice?

Taking their own culture so seriously, the French could not see these domains as anything other than parts of France:

la civilisation française

was indivisible. Everywhere French was used for administration, and instituted as the language of instruction in secondary and higher education, even where—as in Indo-China and North Africa—there was an ancient tradition of literacy in some other language.

*

Colonials could in most places aspire to full French citizenship.

But, except in Algeria—where the native, Muslim, population were far less ready to see their Christian conquerors as role models—the French were always too thin on the ground truly to propagate their own society. There were few solid economic reasons to bring them out to these countries, or to keep them there, and rather soon it showed. In contrast to what happened in the other European empires, the typical Frenchman abroad remained a military man, a doctor, a missionary or a teacher. Napoleon, the pre-eminent French soldier, had famously slighted England as

’une nation de petits commerαants’

—a nation of shopkeepers—but it was precisely the lack of such people in the French colonies which demonstrated how unstable they were. Unlike Portuguese, Spanish, British or even Dutch possessions, there was no part of the French empire which attracted mass immigration. And the French government in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was not able or willing, as it had been in the seventeenth, to finance any emigration. Consequently, French remained, everywhere but Algeria, a language of the governing elite, even while—at least in black Africa—the rest of the population might be heartily aspiring to its values.

The number of colonies under French-speaking administration grew after the end of the First World War, when the German and Ottoman possessions were parcelled out. Cameroon and Togo came to France, and Rwanda and Burundi to Belgium. Syria and Lebanon were also placed under a French mandate. But almost all were granted independence in the fifteen years after the end of the Second World War. The Near Eastern Arab countries were established as independent republics as part of the immediate post-war settlement. Indo-China and North Africa, as well as Madagascar and the Comoros, had to win their freedom by force of arms; in sub-Saharan Africa, by and large they were granted it at their earnest entreaty in 1960. The tiny nations of the Pacific, the Caribbean and South America are still, in effect, part of the empire: but they are now part of the French Union: according to the constitution adopted by the referendum of 27 October 1946,

la France forme avec les peuples d’ outre-mer une Union fondée sur l’ égalité des droits et des devoirs, sans distinction de race ni de religion.

France forms with the overseas peoples a Union founded on equality of rights and duties, without distinction of race nor religion.

And all its members as

ressortissants

(i.e. when they come to France) are French citizens. It is noticeable that language is not included as an aspect in which the Union is free from distinction: that is because in the Union, everyone’s language is expected to be French.

In conformity with its explicit respect for clarity and reason, the French-language community seeks to order itself, and have an overall conception of itself, apparently far more than any other. So it is characteritic that it has given itself an international political, technical and cultural organisation, known as

la francophonie.

It is a matter of some satisfaction to the French government that the initiative for this came not from France but from a number of distinguished second-language speakers. Still, there may perhaps have been a certain political motivation: the founders were President Habib Bourguiba of Tunisia, Prince Norodom Sihanouk of Cambodia, President Léopold Senghor of Senegal, Charles Hélou of Lebanon, and Hamani Diori of Niger. Nevertheless, France does provide up to two-thirds of the organisation’s budget. It was founded on 20 March 1970 at Niamey in Niger, central Africa, and has held summit meetings regularly, with cabinet ministers in attendance, the ninth at Beirut in 2002. Membership is not restricted to former colonies of France; indeed, Egypt recently provided the secretary-general, Boutros Boutros Ghali: characteristically it chooses to emphasise some conceptual or moral, rather than historic, relatedness.

Its current emphasis, rather surprisingly, is on protecting and enabling cultural diversity, certainly a novelty as a francophone preoccupation, and not without a whiff of

l’ esprit malin

, Gallic mischief, directed at the perennial rivals,

les anglo-saxons.

But it is well within the tradition of incisive, and sometimes disinterested, consideration of the rights of man. Political interests will out, however, and it has been difficult for the French state, in recent years, even to protect and foster such linguistic diversity as remains within its own domains. The action of the minister of education in 2002, for example, aimed at incorporating Breton-language schools into the state system, and so funding them nationally, fell foul of an article inserted into the French constitution as late as 1992—that the language of the French Republic is French.

*

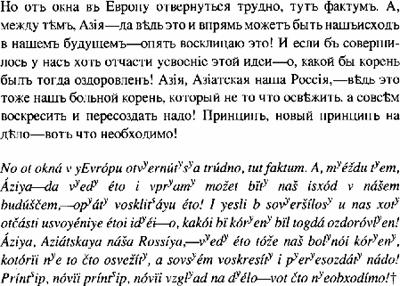

But to turn away from the window on Europe is hard, that is a fact. But, that being said, Asia—this could really be our exodus in our future—again I exclaim it! And if we could accomplish the mastery of that idea, even in part, oh, what a root would then be revitalized! Asia, our Asiatic Russia,—this too is our sick root, which we need not just to refresh, but utterly to resurrect and reconstruct! A principle, a new principle, a new view on the affair, here is what is necessary!

Fyodor M. Dostoyevsky,

Gök-Tepe:

What Is Asia to Us?, 1881

43

Russian, the last of the great European languages spread by an empire, is in many ways unlike the others.

Its domain was extended not by seaborne expeditions but overwhelmingly by military campaigns overland; hence it has come to occupy areas in a vast contiguous swath to the south and east from its homeland in the north European plain. Its bounds were expanded for the most part not by traders or missionaries, but by semi-nomadic Cossacks, explorers and military men: not out of enterprise, or a duty to win souls for Christ, but for reasons of rapine, and to buttress the global interests of its state. Russia began its conscious existence with no natural defences against the Turkic-speaking Tatars to its south, and it remained without natural defences against its Slavic-speaking cousins in Poland to the west. It was on the periphery of the cultural area with which it identified, Christian Europe; but it occupied a plain that was easily accessible to horse invaders, and also crossed by a network of navigable rivers. Ice denied it access to the open sea for most of the year. Its only natural defences lay in the severity of its winters, the sheer stickiness of its land in spring and autumn, and the vast distances that its enemies would need to cross in order to penetrate it. Conditions favoured the growth and consolidation of a single large power, with defence in depth: that power we call Russia.

Nevertheless, there were points of similarity with the other successful empire-builders of Europe. There had been a commercial motive for the expansion eastward into Siberia, the drive of outdoorsmen to trap animals for their fur, just as the French, and later the British, were to do in the northern wilderness of Canada. The Russian Orthodox Church was for most of the last millennium a potent symbol of Russian identity,

*

which accompanied the advance of Russia’s forces across south-eastern Europe and north and central Asia to the Pacific Ocean. Since its language was pointedly an antiquated form of Russia’s own, this resembles above all the imperial practice of the Church of England. And just like the British and the French in the nineteenth century, the Russian government consciously planned the later, stages of its global expansion. Central Asia, specifically the ‘Silk Road’ area of Turkestan south of the Aral Sea, was invaded in 1871-81 to protect the southern border, and as a prime source of cotton. Above all, the long-term spread of the Russian language within these vastly expanded borders was guaranteed by a flow of Russian-speaking immigrants out of the north-east into the newly Russian territories: after the 1861 abolition of the serfdom that had tied them to the land, half a million sought better fortunes eastward into Siberia in the rest of the nineteenth century.

†