Escapes! (15 page)

About 70 gladiators had made it out. Now they'd need a plan if they were to have a chance of staying free. They chose their leaders on the spot. Two Gauls, Crixus and another man named Oenomaus, were quickly voted captains. But the overwhelming choice for commander was Spartacus. It was obvious to all that the Thracian had the brains and the courage to help them survive. What was more, Spartacus had a special insight into the enemy, having fought in their ranks. That could prove to be a valuable weapon.

But first, the new leaders agreed, they must get out of Capua.

Suddenly, distant shouts and the sound of running feet made Spartacus look up. From all directions, armed citizens were running down the city streets. In moments the escapers would be cornered.

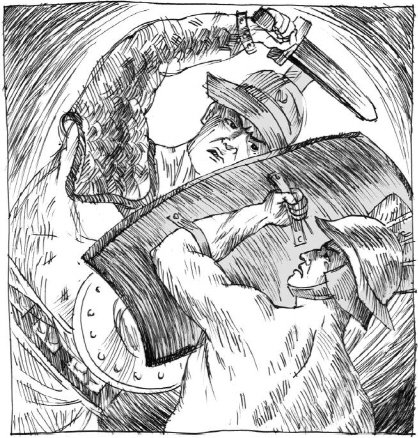

Their backs to the wall, the gladiators clenched their swords and braced themselves for the attack. But in the fierce struggle that followed, the locals were no match for men trained to fight and desperate to stay free. The gladiators quickly overpowered and disarmed them.

Spartacus picked up a Roman weapon and balanced its weight in his hand. With his other hand he threw down the gladiator's sword he'd been holding, as did the others. Barbaric object, he thought. Tainted with dishonor. He'd never touch one again.

In Rome, the senators listened impatiently to the messenger's story of gladiators breaking out of a school in Capua. Let the local forces take care of it, they sniffed. Then word came that the rebels had left the city. A slave named Spartacus had led his followers up the treacherous mountain path to the very top of Mount Vesuvius. The gladiators had set up a camp in the volcano's crater. Worse, other runaway slaves were joining them daily, and their growing numbers posed a risk to the region.

Very well, the Roman authorities sighed. They would send a Roman commander. Not a consul â it would be beneath his dignity â but a praetor, a lesser official. They'd draft a force of 3,000 men to put under his command. That kind of muscle would surely put a quick end to the revolt, the senate reasoned. There was no need to use Rome's highly trained regular army. They were dealing with

slaves,

after all.

In a confident and boastful mood, the newly drafted troops marched swiftly south to the foot of Vesuvius. There they prepared to surround and lay siege to the rebel slaves.

High above, Spartacus and his scouts peered over the tangle of wild vines that covered the mountaintop, and watched grimly as the Roman army gathered in numbers far below. Roman guards were taking up their posts along the narrow road up the mountain â the only route down. All the other sides of the mountain were as steep and smooth as cliffs.

“They're trapping us,” the scouts muttered. “We'll starve up here.”

Spartacus was silent for a moment. “If it comes to that,” he said at last, “I'd rather die by steel than perish by hunger.”

Without another word he crept back from the edge and turned toward the camp in the crater. He wasn't going to give in so easily. Glancing up, he noticed the sun was already high in the sky. There was much to do before dark.

Spartacus put the gladiators to work until nightfall, ripping out the vines that grew all around them. Carefully they twisted the stems into chains, until they were long enough to snake down the face of the mountain. When darkness came they were ready.

Fastening their ropes to the cliff top, the slaves silently scaled down one of the steep, unguarded mountainsides. Above them, one gladiator stayed behind with the weapons until the last of his companions had reached the foot of the mountain. Then he rapidly tossed down the weapons one by one. When the last weapon hit the ground below, he slithered down the vines himself.

The slaves crept silently around the base of the mountain, circling the sleeping Roman camp from behind. Spartacus and his captains paused, listening in the dark for any sounds of enemy movement. But they heard nothing, only their own breathing. Then, at a signal from Spartacus, the slaves rushed forward in a fierce surprise attack. Overwhelmed and bewildered in the darkness, many of the Roman soldiers fled. Spartacus and his followers seized the camp and plundered it for weapons and supplies.

It was a stunning victory, beyond their hopes. And to the slaves of the surrounding countryside, it was the moment they'd dreamed of. Herdsmen and shepherds from the region ran to join the gladiators, who welcomed them. Spartacus knew how valuable such men could be. Their work made them strong and fast, and they could handle weapons â defending their flocks against wild animals and thieves had taught them that. Then came slaves fleeing from surrounding farms. Many weren't trained to fight, but they put their skill at weaving baskets from branches to good use, making shields for the rebels.

Spartacus quickly organized the newcomers according to their skills. Some were given heavy weapons, some turned into light-armed troops, others were made scouts. This was no longer a band of runaways. They were an army now. And a threat that Rome could no longer ignore.

Burning with shame, the Roman Republic sent another praetor to lead soldiers against Spartacus â with orders to swiftly undo the dishonor of the first one's failure.

The Roman defeats that followed were humiliating. The slave army harried the Romans with sudden attacks, surprising one commander while he was bathing, stealing another commander's horse out from under him! Frightened, Roman soldiers began to desert the army. A few tried to join Spartacus, but he turned them away. All the while Spartacus's army grew, from hundreds to thousands. Now, slaves boldly ran from their masters' homes to join them as they passed. The sight of the gladiator army made two things clear. Escape from slavery was possible, and even the Roman army couldn't force them back!

Rome no longer worried about the indignity of fighting slaves. This was no sordid rebellion. The slave army had swelled to tens of thousands of men and women and was moving freely through southern Italy. The whole Roman way of life â balanced so carefully upon slavery â was at risk of falling to pieces. Now fear spurred the Roman senate to put both of the Republic's consuls in command of two legions of infantry and cavalry, over 10,000 men. This time they would fight as they would against a powerful enemy.

But Spartacus knew better than to take on the full force of the Roman army. Some of his men, thrilled by their victories, clamored to march on Rome itself. Spartacus proposed another goal â they would march north to the Alps, and out of Italy to freedom.

“We'll cross the mountains, and then every one to his own homeland. To Gaul, to Germany... and to Thrace.”

As the mid-winter of 71 B.C. approached, Spartacus stood on the southernmost tip of Italy and gazed out over the choppy waves. He and his army were camped on the bank of the Strait of Messina. Across the water lay the island of Sicily. He was about as far from the Alps as he could be.

It had been a stormy two years. The march north to the mountains had been slowed by arguments among Spartacus's followers, who had become unruly and hard to control. Many were overconfident, fired up by their freedom and victories, and thought only of sweeping through the cities of Italy for plunder.

“It's not gold and silver we need,” Spartacus had warned them, “but iron and copper.” Basic material for weapons and survival would keep them alive, not stolen ornaments and jewelry.

Other commanders in the slave army had taken revenge on their Roman prisoners of war, holding gladiatorial games and forcing the Roman prisoners to fight each other. Crixus had even split from Spartacus, taking with him a huge number of German slaves. On their own, Crixus's men had been savagely defeated by the consuls' forces.

Yet the two Roman legions had been powerless to stop the bulk of Spartacus's army, and the slaves kept pushing north. Then, just as freedom had seemed within their reach, a Roman governor of Gaul had moved thousands of his soldiers to block the slaves' escape route through the Alps. Spartacus had been forced to turn back. He led his army south, sticking to remote areas far from the cities.

The defeated Roman consuls had been recalled to Rome in disgrace, and it was revealed that their armies had been stripped of much of their weaponry by the slaves. At last the Roman senate grasped the danger they faced. They quickly named Crassus, a well-born and respected commander, as the general in charge of the war, and placed under his command eight legions of the best trained troops. And if Crassus did not crush the slaves fast enough, the famous commander Pompey would be summoned from Spain to finish the job.

That was the last thing Crassus wanted. Pompey was his rival for power, and he knew that whoever arrived last would take credit for winning the war. Crassus was determined to destroy the slave army before Pompey returned. His first action was to make sure his troops were more afraid of him than of Spartacus, and he harshly punished deserters and any soldiers accused of cowardice. Then he prepared for a massive onslaught against the slaves.

Now, almost two years after the breakout at Capua, Spartacus knew that despite all the victories, his army could not hold out any longer. On reaching the southern shores of Italy, Spartacus had bargained with Cilician pirates to take his men in their ships across the strait to Sicily. He knew that a slave revolt had been crushed on that island only a few years before, and he guessed that the memory of it would still be vivid there. Perhaps he and his followers could rekindle the sparks of rebellion.

The pirates took gifts from Spartacus and promised to return with more ships. But Spartacus waited in vain for them on the seacoast. In the meantime, Crassus had followed him south, and set up camp behind the slave army. There, he began to build a fortified wall lined with sharpened stakes and fronted with a deep ditch.

At first Spartacus laughed at the wall. But not for long. The barrier soon stretched from shore to shore straight across the neck of land that led to the southern tip of Italy. Crassus had trapped Spartacus between his wall and the sea.

But Spartacus had not yet run out of tricks. On a snowy winter night, he ordered his men to begin filling a part of the trench with earth and branches. Before Crassus was aware of what was happening, a third of the slave army had crossed the trench and clambered over the wall, and the rest soon forced their way across. Spartacus hoped that if they moved swiftly east to the port of Brundisium, they might sail from Italy across the Adriatic Sea.

He knew it was their last chance for escape, but by now many of his troops thought too highly of themselves to listen to their commander. Spartacus's strategy of sudden attacks followed by retreat â so successful in the past â now seemed beneath them. They were tired of staying on the defensive, forever on the move.

The slender thread of control Spartacus still held over his army snapped at last. Crassus's legions had been close on their heels for days, as the Roman general hoped to force a battle before Pompey's return. Spotting Crassus's nearby camp, a number of hotheaded slaves rushed to attack the soldiers nearest them. In no time, men from either side were leaping into the fray.