Essence and Alchemy (4 page)

Read Essence and Alchemy Online

Authors: Mandy Aftel

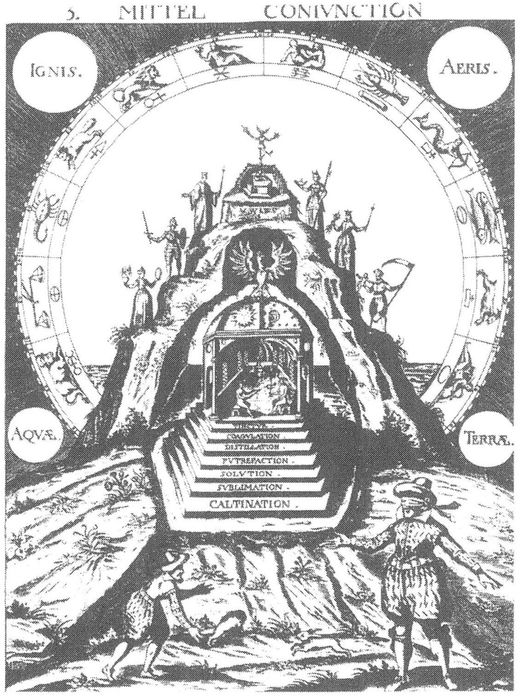

Alchemical work, from Michelspacher's Cabala, Augsburg, 1616

In their preoccupations, alchemists can be said to have much in common with priests (albeit heretical ones), but it is more to the point to say that the distinctions between religion, medicine, science, art, and psychology were not nearly so absolute in their time as they are now. Nor was the boundary between matter and spirit so firm. As Titus Burckhardt observes:

For the people of earlier ages

21

, what we today call matter was not the same as for people of today, either as regards the concept or the experience. This is not to say the so-called primitive peoples of the world only saw through a veil of “magical and compulsive imaginings” as certain ethnologists have supposed, or that their thinking was “alogical” or “pre-logical.” Stones were just as hard as today, fire was just as hot, and natural laws just as inexorable â¦

21

, what we today call matter was not the same as for people of today, either as regards the concept or the experience. This is not to say the so-called primitive peoples of the world only saw through a veil of “magical and compulsive imaginings” as certain ethnologists have supposed, or that their thinking was “alogical” or “pre-logical.” Stones were just as hard as today, fire was just as hot, and natural laws just as inexorable â¦

According to Descartes, spirit and matter are completely separate realities, which thanks to divine ordination come together only at one point: the human brain. Thus the material world, known as “matter,” is automatically deprived of any spiritual content, while the spirit, for its part, becomes the abstract counterpart of the same purely material reality, for what it is in itself, above and beyond this, remains unspecified.

As science and reason gained ground, alchemy went into eclipse (although some important scientists, most notably Isaac Newton,

practiced it). The practical legacy of the alchemists passed to the chemists, who put it in service of the effort to dissect and analyze the elements of the natural world. The spiritual legacy of the alchemists can be seen as having passed to the psychologists, who strive like alchemists to reconcile dualities. “All alchemical thinking

22

is concerned with opposites, states we know in our psychological being as mind and body, love and hate, good and evil, conscious and unconscious, spirit and matter,” writes Nathan Schwartz-Salant in

The Mystery of Human Relationship

.

practiced it). The practical legacy of the alchemists passed to the chemists, who put it in service of the effort to dissect and analyze the elements of the natural world. The spiritual legacy of the alchemists can be seen as having passed to the psychologists, who strive like alchemists to reconcile dualities. “All alchemical thinking

22

is concerned with opposites, states we know in our psychological being as mind and body, love and hate, good and evil, conscious and unconscious, spirit and matter,” writes Nathan Schwartz-Salant in

The Mystery of Human Relationship

.

Only the perfumers inherited both strands of the alchemical tradition. And for a long time, they retained many of the alchemists' ways as well. Perfumery remained chiefly the domain of private solo practitionersâapothecaries, ladies who mixed their own blends at home, and other anonymous souls. It retained traces of its mystical origins in such recipes as a formula for “How to make a woman beautiful forever,” from the 1555

Les Secrets de Maistre Alexys,

the earliest French perfumery book known: “Take a young raven from the nest; feed it on hard eggs for forty days, kill it, and then distill it with myrtle leaves, talc, and almond oil.”

Les Secrets de Maistre Alexys,

the earliest French perfumery book known: “Take a young raven from the nest; feed it on hard eggs for forty days, kill it, and then distill it with myrtle leaves, talc, and almond oil.”

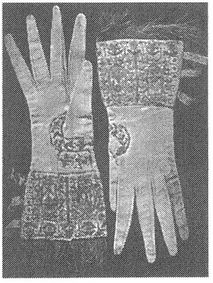

But gradually something resembling a perfume business began to take shape. At first it was an outgrowth of the glove industry, owing to the popularity of perfumed gloves in France from the sixteenth century on. They were worn to keep the skin soft; some people even wore them to bed. Catherine de Medici's perfumer, René

23

, made glovesâand more. When Catherine wished to get rid of her enemies, she turned to him for sorcery, with effective results. Jeanne d'Albret, mother of Henry IV of France, was poisoned after she donned a pair of perfumed gloves presented to her by Catherine.

23

, made glovesâand more. When Catherine wished to get rid of her enemies, she turned to him for sorcery, with effective results. Jeanne d'Albret, mother of Henry IV of France, was poisoned after she donned a pair of perfumed gloves presented to her by Catherine.

Queen Elizabeth's perfumed gloves

René opened the first perfume shop in Paris, probably the first in France. Soon everyone who was anyone flocked there. On the ground floor he sold perfumes, unguents, and cosmetics to the public, but a select few were invited into the chambers above, where René kept alive the alchemical legacy of his profession.

In the shop, which was large and deep, there were two doors, each leading to a staircase. Both led to a room on the first floor, which was divided by a tapestry suspended in the centre, in the back portion of which was a door leading to a secret staircase. Another door opened to a small chamber, lighted from the roof, which contained a large stove, alembics, retorts, and crucibles; it was an alchemist's laboratory.

In the front portion of the room on the first floor were ibises of Egypt; mummies with gilded bands; the crocodile yawning from the ceiling; death's heads with eyeless sockets and gumless teeth, and here old musty volumes, torn and rateaten, were presented to the eye of the visitor in pell-mell confusion. Behind the curtain were phials, singularly-shaped boxes and vases of curious construction; all lighted up by two silver lamps which, supplied with perfumed oil, cast their yellow flame around the somber vault, to which each was suspended by three blackened chains.

It was said of Anne of Austria that with fair linen and perfumes one could entice her to Hades. Known for her beautiful hands, Anne was another glove fanatic. She sent to Naples for them, though she is credited with saying that the perfect glove is made of leather prepared in Spain, cut in France, and finished in England. Gloves of mouse skin were fashionable at her court as well. It was Anne's son Louis XIV who granted a charter to the guild of

gantiers-parfumeurs

in 1656.

gantiers-parfumeurs

in 1656.

Shop of René the perfumer

In the meantime, perfumers were rapidly acquiring a varied palette of natural ingredients and the sophistication to use them imaginatively. Benzoin, cedarwood, costus root, rose, rosemary, sage, juniperwood, frankincense, and cinnamon had been in use since ancient times. Between 1500 and 1540, angelica, anise, cardamom, fennel, caraway, lovage, mace, nutmeg, celery, sandalwood, juniper berries, and black pepper were added to the aromatic repertoire of distilled oils. The years between 1540 and 1589 saw the addition of basil, melissa, thyme, citrus, coriander, dill, oregano, marjoram, galbanum, guaiacwood, chamomile, spearmint, labdanum, lavender, lemon, mint, carrot seed, feverfew, cumin, myrrh, cloves, opoponax, parsley, orange peel, iris, wormwood, and saffron. Drawing upon this burgeoning assortment, in 1725 Johann Farina of Cologne introduced his famous Eau de Cologne, which was based on a mixture of citrus and herbal odors. By 1730 peppermint, ginger, mustard, cypress, bergamot, mugwort, neroli, and bitter almond had further increased the range of possibilities for the perfumer.

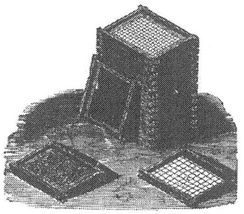

Although distillation could be used on roses, the fragrances of other flowers, such as jasmine, tuberose, and orange flower, eluded that method. They were not coaxed into surrendering their scents until the nineteenth century, when the Frenchman Jacques Passy, inspired by the observation that jasmine, tuberose, and orange flower continue to produce perfume after they have been cut, developed the technique of enfleurage, in which flower petals render their fragrance into a fatty pomade, from which a powerfully scented oil can be derived. Gradually the technique was applied to other florals.

Enfleurage frames

Catherine de Medici had encouraged the development of a perfume industry in France, and in her time Grasse, in southeastern France, had emerged as its center. The climate and soil of the surrounding region proved hospitable to orange trees, acacia, roses, and jasmine. Over time, distillation plants and other facilities for processing perfume materials grew up there; some of them are still operating today.

In tandem with these developments, a retail perfume business was gradually emerging in Europe's larger cities. In early-eighteenth-century London, a Mr. Perry combined the sale of medicines with that of perfume and cosmetics, along the lines of a modern drugstore; one of the products he advertised was an oil of mustard seed that was guaranteed to cure every disease under the sun. In the 1730s, William Bayley set up a shop selling perfumes under the sign of YE OLDE CIVET CATâa popular appellation for London perfumeriesâwhere he was patronized by men and women of fashion. But the first true celebrity perfumer was Charles Lillie

24

, whose shop in London's Strand was a meeting place for the literary and the fashionable. He counted among his friends Jonathan Swift, Joseph Addison, Richard Steele, and Alexander Pope. Both Addison and Steele praised him copiously in print, and Steele went so far as to suggest that he “used the force of magical powers to add value to his wares.”

24

, whose shop in London's Strand was a meeting place for the literary and the fashionable. He counted among his friends Jonathan Swift, Joseph Addison, Richard Steele, and Alexander Pope. Both Addison and Steele praised him copiously in print, and Steele went so far as to suggest that he “used the force of magical powers to add value to his wares.”

Lillie was a crusader for standards in the perfume business, and in his book

The British Perfumer

he set out to educate the public on how to evaluate scented goods, in terms that seem oddly prescient:

The British Perfumer

he set out to educate the public on how to evaluate scented goods, in terms that seem oddly prescient:

As numbers of those who keep shops, and style themselves Perfumers, as well as most buyers, are entirely ignorant, the former of the nature of what they sell, and the latter of what they purchase; it may not, perhaps, be thought amiss, at some time, to make them public ⦠Though this account of numbers of the present pretenders to the perfuming trade may seem to bear hard on them; yet, for the sake of rescuing so curious an art from entire oblivion, and from the hand of ignorance; also for the information of the public, and lastly for the sake of truth; some work of this nature is become absolutely necessary: more particularly, as, without it, the present race of pretenders may continue to sell what they please, under whatever names they please, without having the least regard (as is notoriously the case) to its being genuine, if simple; or, properly prepared, if a compound substance ⦠Another design in the construction of this work, was to inform the real Perfumer (for the pretenders are above being taught) how, where, and at what seasons, he may purchase his several commodities; how to judge their goodness; and how to preserve them against accidents or untoward circumstances, which bring on either a partial or total dissolution, and by which the best perfumes are converted into the most nauseous and fetid odors.

Other books

The Spy's Reward by Nita Abrams

Our Dried Voices by Hickey, Greg

Sandra Hill by Love Me Tender

Broken Play by Samantha Kane

A Boat Made of Bone (The Chthonic Saga) by Grotepas, Nicole

Encounters 1: The Spiral Slayers by Rusty Williamson

Baiting the Boss by Coleen Kwan

Salesmen on the Rise by Dragon, Cheryl

Kiss Me, Katie by Tillery, Monica

The Blood Sigil (The Sigilord Chronicles Book 2) by Hoffman, Kevin