Essence and Alchemy (5 page)

Read Essence and Alchemy Online

Authors: Mandy Aftel

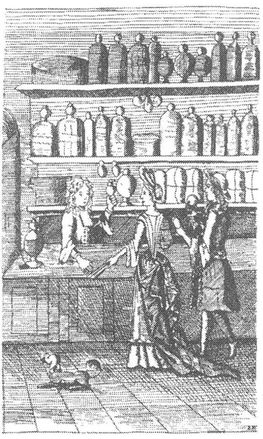

Lillie's was an early entry in what became a burgeoning genre of “how-to” perfume literature, reaching its apex in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Along with formulas for perfumes, these volumes include discourses on flower farming, ancient cultures and their rituals, recipes for hair dyes (often containing lead), remedies for ailments of man and beast (including opiates), and ruminations on society and woman's place therein. The discourses are charming and odd, and the books are illustrated with lovely woodcuts depicting

botanicals and extraction devices. But the perfume information itself is repeated almost verbatim from book to book, with only a small increment of new material, and the formulas themselves are generic; there is no sense in them of a creator's unique signature.

botanicals and extraction devices. But the perfume information itself is repeated almost verbatim from book to book, with only a small increment of new material, and the formulas themselves are generic; there is no sense in them of a creator's unique signature.

The recipes these books contain fall into two categories: those for handkerchief perfumes and those for simulating the scents of certain flowers that resisted distillation, enfleurage, or any other means of rendering then available. The latter were considered the essence of how a refined woman should smell. The formulas worked on the premise of like with like, combining a few intense and similarly scented florals to arrive at a single, sweet floral note, with perhaps a bit of vanilla for additional sweetness, and sometimes a drop of civet, ambergris, or musk for staying power. The standard repertoire included lily of the valley, white lilac, magnolia, narcissus, honeysuckle, heliotrope, sweet pea, and violet. For example, the scent of lily of the valley could be approximated with a mixture of orange flower, vanilla, rose, cassie, jasmine, tuberose, and bitter almond. Eugene Rimmel hails the manufacture of such concoctions as “the truly artistic part

25

of perfumery, for it is done by studying the resemblances and affinities, and blending the shades of scent as a painter does the colors on his palette.” But in truth they exploited none of the range of contrast and intensity offered by the essential oils then available.

25

of perfumery, for it is done by studying the resemblances and affinities, and blending the shades of scent as a painter does the colors on his palette.” But in truth they exploited none of the range of contrast and intensity offered by the essential oils then available.

Perfumer's shop, seventeenth century

The blending of mixtures for scenting handkerchiefs was also considered a high art. Again, each of the collections repeats recipes for Alhambra Perfume, Bouquet d'Amour, Esterhazy Bouquet, Ess Bouquet, Eau de Cologne, Jockey Club, Stolen Kisses, Eau de Millefleurs, International Bouquet of All Nations, and Rondeletia. They usually sound more interesting than they smell. Like the floral imitations, most of them are heavy floral mixtures fixed with civet, musk, or ambergris. A few venture a little further afield. Esterhazy includes vetiver and sandalwood; the colognes feature citruses as well as rosemary. True to its name, International Bouquet blends rose from Turkey, jasmine from Africa, lemon from Sardinia, vanilla from South America, lavender from England, and tuberose from France. Millefleurs includes everything but the kitchen sink. Rondeletiaâa mixture of lavender and clovesâwas considered a daring innovation. But even these rareties were composed of materials that are essentially similar in tone and value, in keeping with the composition principles enforced by the perfume guides:

It may be useful

26

⦠to warn the amateur operator against the promiscuous mingling of different scents in a single preparation, under the idea that, by bringing an increased number of agreeable perfumes together, the odor of the resulting compound will be richer. Some odors, like musical sounds, harmonize when blended, producing a compound odor combining the fragrance of each of its constituents, and fuller and richer, or more chaste and delicate, than either of them separately; whilst others appear mutually antagonistic or incompatible, and produce a contrary effect.

26

⦠to warn the amateur operator against the promiscuous mingling of different scents in a single preparation, under the idea that, by bringing an increased number of agreeable perfumes together, the odor of the resulting compound will be richer. Some odors, like musical sounds, harmonize when blended, producing a compound odor combining the fragrance of each of its constituents, and fuller and richer, or more chaste and delicate, than either of them separately; whilst others appear mutually antagonistic or incompatible, and produce a contrary effect.

So while each perfume vendor peddled his own Rondeletia or Eau de Cologne from his shop or cart, they all stayed within an extremely

limited range. It was like being a painter and using only a quarter of the color wheel.

limited range. It was like being a painter and using only a quarter of the color wheel.

The striking exception was Peau d'Espagne (Spanish skin), a highly complex and luxurious perfume originally used to scent leather in the sixteenth century. Chamois was steeped in neroli, rose, sandalwood, lavender, verbena, bergamot, cloves, and cinnamon, and subsequently smeared with civet and musk. Bits of the leather were used to perfume stationery and clothing. It was a favorite of the sensuous because of the musk and civet, and also because of the leather itself, which may have stirred ancestral memories of the sexual stimulus of skin odor. (Perhaps this explains the passions of old book collectors and shoe freaks as well as leather fetishists.)

By 1910 Peau d'Espagne was being made as a perfume, by adding vanilla, tonka, styrax, geranium, and cedarwood to the original formula used to scent leather. Peter Altenberg, one of the Vienna Coffeehouse Wits and the embodiment of the turn-of-the-century bohemian, recalls:

As a child

27

I found in a drawer in my beloved, wonderfully beautiful mother's writing table, which was made of mahogany and cut glass, an empty little bottle that still retained the strong fragrance of a certain perfume that was unknown to me.

27

I found in a drawer in my beloved, wonderfully beautiful mother's writing table, which was made of mahogany and cut glass, an empty little bottle that still retained the strong fragrance of a certain perfume that was unknown to me.

I often used to sneak in and sniff it.

I associated this perfume with every love, tenderness, friendship, longing, and sadness there is.

But everything related to my mother. Later on, fate overtook us like an unexpected horde of Huns and rained heavy blows down on us.

And one day I dragged from perfumery to perfumery, hoping by means of tiny sample vials of the perfume from the writing table of my beloved deceased mother to discover

its name. And at long last I did: Peau d'Espagne, Pinaud, Paris.

its name. And at long last I did: Peau d'Espagne, Pinaud, Paris.

I then recalled the times when my mother was the only womanly being who could bring me joy and sorrow, longing and despair, but who time and again forgave me everything, and who always looked after me, and perhaps even secretly in the evening before going to bed prayed for my future happiness â¦

Later on, many young women on childish-sweet whims used to send me their favorite perfumes and thanked me warmly for the prescription I discovered of rubbing every perfume directly onto the naked skin of the entire body right after a bath so that it would work like a true personal skin cleansing! But all these perfumes were like the fragrances of lovely but poisonous exotic flowers. Only Essence Peau d'Espagne, Pinaud, Paris, brought me melancholic joys although my mother was no longer alive and could no longer pardon my sins!

Peau d'Espagne (

sans

leather) continued to be made as a perfume and lost none of its sensuous appeal over the decades, but it was an exception to a generally tame and uninspired approach to perfume. I gave up on using the formulas spelled out in the literature of the period after I turned to them in the process of designing a fragrance for a shop that had asked me to come up with something light, floral, and sweet. Each of the imitation floral blends I tried had the same problems. The overpowering odor of bitter almond made them smell cloying and dated. More important, the perfumes had no real construction; they were just a mishmash of florals that cost a fortune, with some animal scents thrown in as fixatives. They were unimaginative and clichéd and unusable.

sans

leather) continued to be made as a perfume and lost none of its sensuous appeal over the decades, but it was an exception to a generally tame and uninspired approach to perfume. I gave up on using the formulas spelled out in the literature of the period after I turned to them in the process of designing a fragrance for a shop that had asked me to come up with something light, floral, and sweet. Each of the imitation floral blends I tried had the same problems. The overpowering odor of bitter almond made them smell cloying and dated. More important, the perfumes had no real construction; they were just a mishmash of florals that cost a fortune, with some animal scents thrown in as fixatives. They were unimaginative and clichéd and unusable.

It is not in the recipes per se that the spirit of the alchemist lived on, but in the information these old books offer on the history of

perfume, their commentaries on the nature of the ingredients, and the occasional imaginative suggestion for combining them. But it was not until the last decade of the nineteenth century and the first two decades of the twentieth that perfume composition began to take on the attitudes, creativity, and license of a true art form. “Modern perfume

28

came into being in Paris between 1889 and 1921,” writes the perfume researcher and writer Stephan Jellinek. “In these thirty-two years, perfumery changed more than it had during the four thousand years before.”

perfume, their commentaries on the nature of the ingredients, and the occasional imaginative suggestion for combining them. But it was not until the last decade of the nineteenth century and the first two decades of the twentieth that perfume composition began to take on the attitudes, creativity, and license of a true art form. “Modern perfume

28

came into being in Paris between 1889 and 1921,” writes the perfume researcher and writer Stephan Jellinek. “In these thirty-two years, perfumery changed more than it had during the four thousand years before.”

Perfumers began to roam far beyond their timid beginnings in Rondeletia and Eau de Cologne to create scents that were conceived not as copies of scents found in nature but as beautiful in themselves. No longer shackled to the traditional recipes, perfumers were free to use their materials as liberally as an artist works with color, or a musician with tone. “It was, for the first time

29

in history, an aesthetic based on contrast rather than harmony,” Jellinek writes. “Pungent herbal and dry woody notes were used alongside the soft and narcotic scents of subtropical flowers, the cool freshness of citrus fruits offset the languorous warmth of balsams and vanilla, the innocence of spring flowers was paired with the seduction of musk and civet. A sense of harmony was, of course, maintained in all this, but it was a harmony of a higher, more complex order. The sophisticated harmony of artistic creation had replaced the simple harmony of Nature.”

29

in history, an aesthetic based on contrast rather than harmony,” Jellinek writes. “Pungent herbal and dry woody notes were used alongside the soft and narcotic scents of subtropical flowers, the cool freshness of citrus fruits offset the languorous warmth of balsams and vanilla, the innocence of spring flowers was paired with the seduction of musk and civet. A sense of harmony was, of course, maintained in all this, but it was a harmony of a higher, more complex order. The sophisticated harmony of artistic creation had replaced the simple harmony of Nature.”

This period of creative ferment coincided withâand was, to a degree, spurred on byâthe introduction of synthetically formulated perfume ingredients. Coumarin, which was designed to replicate the smell of freshly mowed hay, appeared around 1870. It was derived from tonka beans, but it was a quarter the price of essence of tonka itself, inexhaustible, and therefore independent of market fluctuations. Vanillin, to imitate vanilla, followed next, and had what was seen as the great virtue of colorlessness. These cheaper chemicals

were offered by the same suppliers who sold natural ingredients, but they were only too happy to avail themselves of consistent quality and steady supply.

were offered by the same suppliers who sold natural ingredients, but they were only too happy to avail themselves of consistent quality and steady supply.

Jicky by Guerlain was the first modern perfume. Created in 1889, it was

a fougère,

or fern fragrance, based on coumarin. It also included linalool (naturally occurring in bois de rose) and vanillin (naturally occurring in vanilla). To this synthetic cocktail were added lemon, bergamot, lavender, mint, verbena, and sweet marjoram, plus civet as a fixative. It was a significant departure from the perfumes that preceded it: Jicky had nothing to do with replicating the smells found in nature. It was also a great success, its popularity building over the next twenty years as women became more venturesome in their perfume choices.

a fougère,

or fern fragrance, based on coumarin. It also included linalool (naturally occurring in bois de rose) and vanillin (naturally occurring in vanilla). To this synthetic cocktail were added lemon, bergamot, lavender, mint, verbena, and sweet marjoram, plus civet as a fixative. It was a significant departure from the perfumes that preceded it: Jicky had nothing to do with replicating the smells found in nature. It was also a great success, its popularity building over the next twenty years as women became more venturesome in their perfume choices.

Bundle of vanilla

The perfume community was initially cautious about employing the cheap new synthetics. Perfumers were well aware of the depth and beauty of the naturals, and at first used the synthetics only to amplify or modulate them. As late as 1923, a guide cautioned, “Artificial perfumes obviously present

30

great resources to the manufacturers of cheap extracts, but in the manufacture of fine perfumes they can only serve as adjuncts to natural perfumes, either to vary the âshade' or ânote' of the odors, or to increase ⦠intensity.” But by then the perfume industry, lured by the cheapness, stability, and colorlessness, had largely abandoned its reservations and embraced the synthetics wholeheartedly.

30

great resources to the manufacturers of cheap extracts, but in the manufacture of fine perfumes they can only serve as adjuncts to natural perfumes, either to vary the âshade' or ânote' of the odors, or to increase ⦠intensity.” But by then the perfume industry, lured by the cheapness, stability, and colorlessness, had largely abandoned its reservations and embraced the synthetics wholeheartedly.

The shift can be traced

31

in the twice yearly reports, from 1887 to

1915, of Schimmel and Co. (later renamed Fritzsche Brothers), which was one of the major suppliers of essential oils at the turn of the century. At first they chart the fluctuations in the supply of natural ingredients, as territories are colonized and recolonized, and their resources and labor exploited to provide materials of better quality at competitive prices. But gradually, more and more of the catalog pages are devoted to the wonders of synthetic ingredients, described in copy that increasingly hypes the virtues of the new. An 1895 report introduces Schimmel's first synthetic jasmine; by 1898 the catalog notes, “The demand for this specialty has gradually increased as to induce us to extend our arrangements for its manufacture on a larger scale. At the same time we are able to offer it at a considerably reduced price, in place of the extracts made from jassamine pomatum.” Three years later, the catalog vaunts the superiority of the synthetic version: “The natural extracts from flowers excel in delicacy of aroma, the artificial products being stronger, more lasting, and cheaper.” And a year later, “The use of this perfume, which we were the first to introduce into commerce, has become more and more general. It may now already be counted among the most important auxiliaries of the perfume trade, and it has recently also been improved to such an extent, that in quality it so nearly approaches the natural product, that, in dilution, the one can scarcely be distinguished from the other.”

31

in the twice yearly reports, from 1887 to

1915, of Schimmel and Co. (later renamed Fritzsche Brothers), which was one of the major suppliers of essential oils at the turn of the century. At first they chart the fluctuations in the supply of natural ingredients, as territories are colonized and recolonized, and their resources and labor exploited to provide materials of better quality at competitive prices. But gradually, more and more of the catalog pages are devoted to the wonders of synthetic ingredients, described in copy that increasingly hypes the virtues of the new. An 1895 report introduces Schimmel's first synthetic jasmine; by 1898 the catalog notes, “The demand for this specialty has gradually increased as to induce us to extend our arrangements for its manufacture on a larger scale. At the same time we are able to offer it at a considerably reduced price, in place of the extracts made from jassamine pomatum.” Three years later, the catalog vaunts the superiority of the synthetic version: “The natural extracts from flowers excel in delicacy of aroma, the artificial products being stronger, more lasting, and cheaper.” And a year later, “The use of this perfume, which we were the first to introduce into commerce, has become more and more general. It may now already be counted among the most important auxiliaries of the perfume trade, and it has recently also been improved to such an extent, that in quality it so nearly approaches the natural product, that, in dilution, the one can scarcely be distinguished from the other.”

Other books

Ambush on the Mesa by Gordon D. Shirreffs

Vortex by Bond, Larry

Death Logs In by E.J. Simon

Johnny Angel by Danielle Steel

Nerves of Steel by Lyons, CJ

An Explosive Time (The Celtic Cousins' Adventures) by Hughes, Julia

The Girl From Number 22 by Jonker, Joan

The Chosen One by T. B. Markinson

My Honeymoon With Mr White (BWWM Interracial Romance) by Fielding, J A

What a Woman Desires by Rachel Brimble