Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (9 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

The examiners are only human too: sometimes they are hungry, tired or just bored after previous presentations (particularly if yours is the last long case of the afternoon). Show interest and enthusiasm while speaking. Think of yourself as a news reader and speak at a speed that allows the examiners to keep up and take notes. Do not read your notes in a monotone. The notes are meant to be a memory aid. Break up the pace and include a pregnant pause after you make an important point (for emphasis).

Ideally, the long case should be a discussion between consultants, with the candidate being a respectful junior colleague. The examiners only rarely interrupt during the presentation. If your presentation is taking too long and there will not be time for discussion you will usually be interrupted and asked to summarise. One should aim to have finished presenting the history in less than 12 minutes.

Most examiners expect the candidate to finish their presentation with a list of the main problems they think should be discussed in order of importance. It is useful to ask the patient what he or she thinks is the most important problem with his or her health at the moment and put that close to or at the top of the list of problems, even if it is not the most interesting medical problem.

It is likely that the examiners will want to discuss the patient’s active problems. They will almost always want to talk about the problem the patient sees as most important. These should be the areas of management that you are best prepared for. It is very unsatisfactory for examiners to feel that they have not been told all the major problems, and what the management plan for each problem is, by the end of the discussion. At the end of your presentation, and before discussion of management, the lead examiner may ask some questions to clarify aspects of the history or examination findings. This should be no cause for alarm. After this, you are usually given the opportunity to outline a plan of management or the examiners may ask specific questions. Examining styles differ, but you should strive to direct the discussion tactfully. Being allowed to do this is usually a good sign, but not being allowed to control the discussion is not necessarily a bad sign. Some candidates appear to think that if they speak quickly and loudly enough they may prevent the examiners from asking any questions. This strategy does not work. The exam is meant to be a discussion and if the examiners cannot ask questions the candidate cannot score marks.

When appropriate, ask for one or two important investigations relevant to the problems, rather than rattling off a rote list of routine tests. Examiners find a long list irritating and consider it a sign of an immature approach.

A reason should be given for ordering every test.

For a diagnostic problem it may be useful to ask for the results of previous investigations. Any mentioned test may have to be discussed in detail with the examiners. Sometimes the examiners will not give you the results of a test (they may not have it available), but merely ask how it would help you. We suggest that you write down the results you are told (it is embarrassing to have to ask for the figures to be repeated). Don’t ignore any information that is given; for example, if the haemoglobin value is normal, comment on this and explain how it helps. Many examiners will have underlined or marked the relevant results from a printed pathology or biochemistry report. This is to avoid wasting time as a candidate wades through a series of irrelevant results. Concentrate on the marked results. Remember not to touch X-ray films or criticise the quality of the material shown. Pathological specimens are not shown in the clinical examinations.

Always prepare answers to the obvious lines of question and try to think like a consultant physician who is in charge of the patient’s care (and hypothesise that the patient is a close relative of the examiner!). If there is a diagnostic dilemma, consider the

tests you want and how positive and negative results will support or refute your proposed diagnoses. In a management case, prepare an outline of the suggested treatment and be able to justify it. A good approach to management if the patient is an inpatient is to ask yourself, ‘What steps will be required to get this patient home?’ Always set management goals for all key therapeutic interventions. The examiners may ask about theoretical aspects of the condition. Most often, they will concentrate on the testing of factual knowledge in areas that are necessary for the formulation of adequate management decisions or interpretation of test results. You should think about these areas beforehand. Always consider whether the patient’s current treatment is justified and whether the diagnosis previously made is consistent with the history and examination; it may not be. Do not be afraid to contradict the current management in a restrained way, if there is clear justification.

A common series of questions for many long cases involving chronic diseases includes aspects of how you would discuss the illness and the prognosis with the patient. The examiners might ask: ‘What would you tell Mrs Smith about her prognosis and likely future treatment?’ and ‘What would you advise her about the safety of future pregnancies?’

The examiners will not usually ask hypothetical questions unrelated to the patient being discussed. If you are answering well, the line of questioning may change or the depth may become overwhelming. Do

not

be frightened to say, in the latter situation, ‘I don’t know’, when asked a very difficult question. Obvious wild guesses will be detrimental. If the examiner persists in asking a question, it usually means he or she is trying to establish a basic fact. Talk sensibly around the topic – often a supplementary question will result in recall of the appropriate information. With an especially difficult issue it is reasonable to say you would consult the literature or an appropriate sub-specialist for advice. Remember that examiners are instructed to avoid making snap judgments or failing candidates because of one small mistake. The best examiners will not labour a point. If it is clear you do not know the answer they will move on to another series of questions. This does not mean you have failed, but rather gives you the opportunity to gain marks elsewhere.

You must be able to discuss sensibly anything that you mention in a viva, so don’t casually allude to rare diseases that you know nothing about (e.g. kala-azar as a cause of massive splenomegaly).

The long case rationale

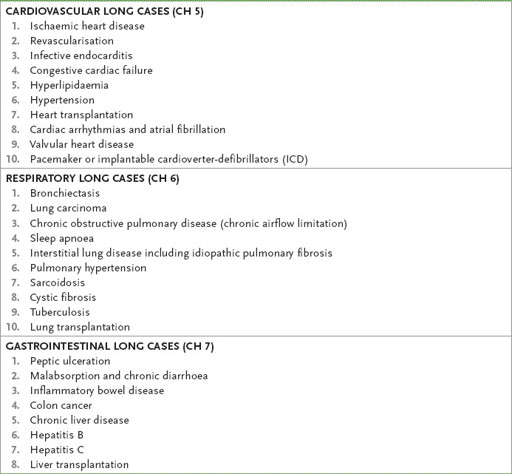

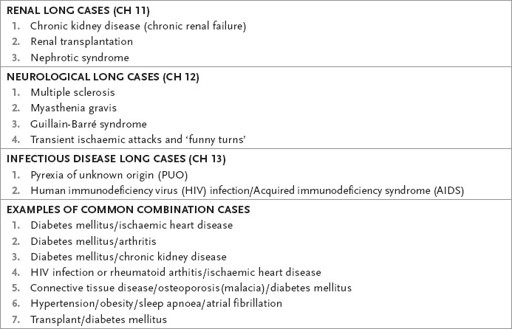

The long case is a test of the candidate’s ability at history-taking, physical examination, interpretation of findings and construction of a diagnosis (and differential diagnosis), and approach to management (investigation and treatment). Important and common long cases are presented in some detail in the next chapters. The list in

Table 4.2

is not exhaustive, but gives an idea of the range of possible cases. Most (but not all) are discussed in

Chapters 5

–

13

. Some other relevant aspects are dealt with in

Chapter 16

. These cases are presented as single problems but most patients will have a combination of problems. Some problems tend to occur together.

Table 4.2

Common long cases

It would be unusual not to see at least one type 2 patient with diabetes on the examination day. These patients are often obese and have diabetic complications and problems related to their obesity such as vascular disease or arthritis. A common question to be asked about such patients would be fitness for surgery such as for a joint replacement. Another likely case is a transplant patient. Transplant patients have

many similar problems as well as the specific issues related to their particular organ failure and original illness. For example, a kidney and pancreas transplant patient may have complications of previous diabetes. It is well worth making an effort to see many patients of this type and have an approach worked out for their management.

Candidates are often very well prepared for common types of long cases and are able to produce a formulaic response to a trigger word such as

diabetes

or

transplant.

The examiners are then given a rote list instead of management directed at the particular patient. It is important always to relate these management lists to the actual patient and adapt them as required. Such an approach reflects the maturity expected at this level.

Another common problem faced by the examiners is the excessively detailed social history which takes up much of the presentation. Relevant social problems should be noted and candidates, if asked, should be able to provide more detail and discuss the problems sensibly, but attempting to replace the more difficult medical aspects of the patient’s care with this will not lead to a successful long case – we anticipate the examiners are on to it!

Types of long case

The cases in

Chapters 5

–

13

are written as a guide to dealing with the long-case examination and are not meant to replace textbook descriptions. To pass, you must really know and understand your general medicine, be able to take a great history, examine accurately, and maturely synthesise all the data. Remember that usually several problems occur in the one case. A patient with an unusual diagnosis will often have one or more common problems as well.

The examiners will often ask whether you would like the results of appropriate investigations. Be prepared to interpret any results you have asked for. Electrocardiograms (ECGs), chest X-rays, and computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans may be shown to candidates. Echocardiograms are not usually shown to candidates, but you are expected to be able to interpret echocardiography reports. Some common examples are included in

Chapters 5

–

13

and also in

Chapter 16

. At the end of each report is a comment that gives an idea of the sort of interpretation expected from candidates.

The key to passing any exam is obviously providing the examiners with what they want. Candidates have plenty of opportunity to find out what examiners want. Practice cases with examiners and senior registrars; the stories (sometimes exaggerated) of previous candidates and information from the College are all readily available these days.

If you can think like an examiner then you can give them exactly what they want. In essence what they want is that you should think like a physician. The College exam is quite successful at producing people who think like physicians. Physicians from all internal medicine specialties have had a common training experience and this makes communication between them easier.

There is a list of basic skills and qualities that an examiner wants you to establish from your long-case presentation.

1.

Are you safe?

2.

Do you know what you are doing and what your limitations are?

3.

If you go on to become a cardiac electrophysiologist, starting next week, do you know enough about say, thyrotoxicosis, to cope with it, with help if necessary?

4.

Have you developed a competent approach to the patient who has problems involving many sub-specialties?