Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things (3 page)

Read Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things Online

Authors: Charles Panati

Tags: #Reference, #General, #Curiosities & Wonders

Broken Mirror: 1st Century, Rome

Breaking a mirror, one of the most widespread bad luck superstitions still extant, originated long before glass mirrors existed. The belief arose out of a combination of religious and economic factors.

The first mirrors, used by the ancient Egyptians, the Hebrews, and the Greeks, were made of polished metals such as brass, bronze, silver, and gold, and were of course unbreakable. By the sixth century

B.C

., the Greeks had begun a mirror practice of divination called catoptromancy, which employed shallow glass or earthenware bowls filled with water. Much like a gypsy’s crystal ball, a glass water bowl—a

miratorium

to the Romans—was supposed to reveal the future of any person who cast his or her image on the reflective surface. The prognostications were read by a “mirror seer.” If one of these mirrors slipped and broke, the seer’s straightforward interpretation was that either the person holding the bowl had no future (that is, he or she was soon to die) or the future held events so abysmal that the gods were kindly sparing the person a glimpse at heartache.

The Romans, in the first century

A.D

., adopted this bad luck superstition and added their own twist to it—our modern meaning. They maintained that a person’s health changed in cycles of seven years. Since mirrors reflect a person’s appearance (that is, health), a broken mirror augured seven years of ill health and misfortune.

The superstition acquired a practical, economic application in fifteenth-century Italy. The first breakable sheet-glass mirrors with silver-coated backing were manufactured in Venice at that time. (See “Mirror,” page 229.) Being costly, they were handled with great care, and servants who cleaned the mirrors of the wealthy were emphatically warned that to break one of the new treasures invited seven years of a fate worse than death. Such effective use of the superstition served to intensify the bad luck belief for generations of Europeans. By the time inexpensive mirrors were being manufactured in England and France in the mid-1600s, the broken-mirror superstition was widespread and rooted firmly in tradition.

Number Thirteen: Pre-Christian Era, Scandinavia

Surveys show that of all bad luck superstitions, unease surrounding the number thirteen is the one that affects most people today—and in almost countless ways.

The French, for instance, never issue the house address thirteen. In Italy,

the national lottery omits the number thirteen. National and international airlines skip the thirteenth row of seats on planes. In America, modern skyscrapers, condominiums, co-ops, and apartment buildings label the floor that follows twelve as fourteen. Recently, a psychological experiment tested the potency of the superstition: A new luxury apartment building, with a floor temporarily numbered thirteen, rented units on all other floors, then only a few units on the thirteenth floor. When the floor number was changed to twelve-B, the unrented apartments quickly found takers.

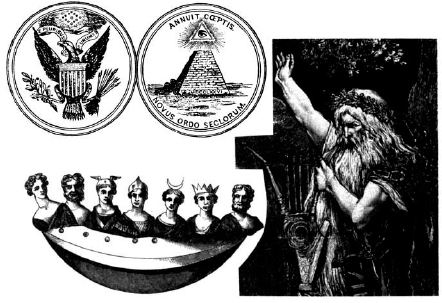

Norse god Balder (right), source of the number thirteen superstition; Norse goddess Frigga, crowned with crescent moon, source of the Friday the thirteenth superstition; American dollar bill symbols incorporate numerous items numbering thirteen

.

How did this fear of the number thirteen, known as triskaidekaphobia, originate?

The notion goes back at least to Norse mythology in the pre-Christian era. There was a banquet at Valhalla, to which twelve gods were invited. Loki, the spirit of strife and evil, gate-crashed, raising the number present to thirteen. In the ensuing struggle to evict Loki, Balder, the favorite of the gods, was killed.

This is one of the earliest written references to misfortune surrounding the number thirteen. From Scandinavia, the superstition spread south throughout Europe. By the dawn of the Christian era, it was well established in countries along the Mediterranean. Then, folklorists claim, the belief was resoundingly reinforced, perhaps for all time, by history’s most famous

meal: the Last Supper. Christ and his apostles numbered thirteen. Less than twenty-four hours after the meal, Christ was crucified.

Mythologists have viewed the Norse legend as prefiguring the Christian banquet. They draw parallels between the traitor Judas and Loki, the spirit of strife; and between Balder, the favorite god who was slain, and Christ, who was crucified. What is indisputable is that from the early Christian era onward, to invite thirteen guests for dinner was to court disaster.

As is true with any superstition, once a belief is laid down, people search, consciously or unconsciously, for events to fit the forecast. In 1798, for instance, a British publication,

Gentlemen’s Magazine

, fueled the thirteen superstition by quoting actuarial tables of the day, which revealed that, on the average, one out of every thirteen people in a room would die within the year. Earlier and later actuarial tables undoubtedly would have given different figures. Yet for many Britons at the time, it seemed that science had validated superstition.

Ironically, in America, thirteen should be viewed as a

lucky

number. It is part of many of our national symbols. On the back of the U.S. dollar bill, the incomplete pyramid has thirteen steps; the bald eagle clutches in one claw an olive branch with thirteen leaves and thirteen berries, and in the other he grasps thirteen arrows; there are thirteen stars above the eagle’s head. All of that, of course, has nothing to do with superstition, but commemorates the country’s original thirteen colonies, themselves an auspicious symbol.

Friday the Thirteenth

. Efforts to account for this unluckiest of days have focused on disastrous events alleged to have occurred on it. Tradition has it that on Friday the thirteenth, Eve tempted Adam with the apple; Noah’s ark set sail in the Great Flood; a confusion of tongues struck at the Tower of Babel; the Temple of Solomon toppled; and Christ died on the cross.

The actual origin of the superstition, though, appears also to be a tale in Norse mythology.

Friday is named for Frigga, the free-spirited goddess of love and fertility. When Norse and Germanic tribes converted to Christianity, Frigga was banished in shame to a mountaintop and labeled a witch. It was believed that every Friday, the spiteful goddess convened a meeting with eleven other witches, plus the devil—a gathering of thirteen—and plotted ill turns of fate for the coming week. For many centuries in Scandinavia, Friday was known as “Witches’ Sabbath.”

Black Cat: Middle Ages, England

As superstitions go, fear of a black cat crossing one’s path is of relatively recent origin. It is also entirely antithetical to the revered place held by the cat when it was first domesticated in Egypt, around 3000

B.C

.

All cats, including black ones, were held in high esteem among the ancient Egyptians and protected by law from injury and death. So strong was cat idolatry that a pet’s death was mourned by the entire family; and both rich and poor embalmed the bodies of their cats in exquisite fashion, wrapping them in fine linen and placing them in mummy cases made of precious materials such as bronze and even wood—a scarcity in timber-poor Egypt. Entire cat cemeteries have been unearthed by archaeologists, with mummified black cats commonplace.

Impressed by the way a cat could survive numerous high falls unscathed, the Egyptians originated the belief that the cat has nine lives.

The cat’s popularity spread quickly through civilization. Sanskrit writings more than two thousand years old speak of cats’ roles in Indian society; and in China about 500

B.C

., Confucius kept a favorite pet cat. About

A.D

. 600, the prophet Muhammad preached with a cat in his arms, and at approximately the same time, the Japanese began to keep cats in their pagodas to protect sacred manuscripts. In those centuries, a cat crossing a person’s path was a sign of

good

luck.

Dread of cats, especially black cats, first arose in Europe in the Middle Ages, particularly in England. The cat’s characteristic independence, willfulness, and stealth, coupled with its sudden overpopulation in major cities, contributed to its fall from grace. Alley cats were often fed by poor, lonely old ladies, and when witch hysteria struck Europe, and many of these homeless women were accused of practicing black magic, their cat companions (especially black ones) were deemed guilty of witchery by association.

One popular tale from British feline lore illustrates the thinking of the day. In Lincolnshire in the 1560s, a father and his son were frightened one moonless night when a small creature darted across their path into a crawl space. Hurling stones into the opening, they saw an injured black cat scurry out and limp into the adjacent home of a woman suspected by the town of being a witch. Next day, the father and son encountered the woman on the street. Her face was bruised, her arm bandaged. And she now walked with a limp. From that day on in Lincolnshire, all black cats were suspected of being witches in night disguise. The lore persisted. The notion of witches transforming themselves into black cats in order to prowl streets unobserved became a central belief in America during the Salem witch hunts.

Thus, an animal once looked on with approbation became a creature dreaded and despised.

Many societies in the late Middle Ages attempted to drive cats into extinction. As the witch scare mounted to paranoia, many innocent women and their harmless pets were burned at the stake. A baby born with eyes too bright, a face too canny, a personality too precocious, was sacrificed for fear that it was host to a spirit that would in time become a witch by day, a black cat by night. In France, thousands of cats were burned monthly until King Louis XIII, in the 1630s, halted the shameful practice. Given the number of centuries in which black cats were slaughtered throughout

Europe, it is surprising that the gene for the color black was not deleted from the species…unless the cat does possess nine lives.

Flip of a Coin: 1st Century

B.C

., Rome

In ancient times, people believed that major life decisions should be made by the gods. And they devised ingenious forms of divination to coax gods to answer important questions with an unequivocal “yes” or “no.” Although coins—ideally suited for yes/no responses—were first minted by the Lydians in the tenth century

B.C

., they were not initially used for decisionmaking.

It was Julius Caesar, nine hundred years later, who instituted the heads/tails coin-flipping practice. Caesar’s own head appeared on one side of every Roman coin, and consequently it was a

head

—specifically that of Caesar—that in a coin flip determined the winner of a dispute or indicated an affirmative response from the gods.

Such was the reverence for Caesar that serious litigation, involving property, marriage, or criminal guilt, often was settled by the flip of a coin. Caesar’s head landing upright meant that the emperor, in absentia, agreed with a particular decision and opposed the alternative.

Spilling Salt: 3500

B.C

, Near East

Salt was man’s first food seasoning, and it so dramatically altered his eating habits that it is not at all surprising that the action of spilling the precious ingredient became tantamount to bad luck.

Following an accidental spilling of salt, a superstitious nullifying gesture such as throwing a pinch of it over the left shoulder became a practice of the ancient Sumerians, the Egyptians, the Assyrians, and later the Greeks. For the Romans, salt was so highly prized as a seasoning for food and a medication for wounds that they coined expressions utilizing the word, which have become part of our language. The Roman writer Petronius, in the

Satyricon

, originated “not worth his salt” as opprobrium for Roman soldiers, who were given special allowances for salt rations, called

salarium

— “salt money” —the origin of our word “salary.”

Archaeologists know that by 6500

B.C

., people living in Europe were actively mining what are thought to be the first salt mines discovered on the continent, the Hallstein and Hallstatt deposits in Austria. Today these caves are tourist attractions, situated near the town of Salzburg, which of course means “City of Salt.” Salt purified water, preserved meat and fish, and enhanced the taste of food, and the Hebrews, the Greeks, and the Romans used salt in all their major sacrifices.

The veneration of salt, and the foreboding that followed its spilling, is poignantly captured in Leonardo da Vinci’s

The Last Supper

. Judas has spilled the table salt, foreshadowing the tragedy—Jesus’ betrayal—that was

to follow. Historically, though, there is no evidence of salt having been spilled at the Last Supper. Leonardo wittingly incorporated the widespread superstition into his interpretation to further dramatize the scene. The classic painting thus contains two ill-boding omens: the spilling of salt, and thirteen guests at a table.